In a school gymnasium, a French woman stranded with a broken down car in South Dakota is introduced to a teen who’s practicing free throws on the basketball court, who tells the woman that she’s nicknamed Magic Johnson. The woman, played by Chiara Mastroianni, tells the girl she’s here from France and asks, “And you? Where are you from?” She answers, “Good question. I wonder that every day.” Even though they’re speaking on an indigenous reservation.

This conundrum is the crux of “Eureka,” Argentinean director Lisandro Alonso’s occasionally beautiful, occasionally beguiling, and occasionally confounding triptych about the material and political issue of colonialism and the spiritual issue of what is home. It’s a movie best received in a relaxed frame of mind. Because much of it is a slow burn, if there’s indeed a burn at all. The first twenty-five minutes notwithstanding, this is not a picture that delivers much in the narrative momentum department.

Those opening minutes first serve up stark images of an Indigenous man on a crag, singing, we presume (there are no subtitles), the songs of his people. After that, we are treated to a Western of sorts, one in which Indigenous people are conspicuous in their absence.

Viggo Mortenson plays a lone, reasonably determined man on a mission. He shoots the man who won’t let him a room, and presumably, he similarly dispatches the two corpses we later see in a bed where he’s slept. The segment both indulges and upends genre cliches. Mastroianni plays a character who resembles Joan Crawford’s Vienna in “Johnny Guitar.” When we hear an Irish song being sung off-screen, we think of perhaps a variant of Marlene Dietrich’s backroom chanteuse in “Destry Rides Again.” Turns out the singer is a nun. And so on. The sere landscapes here tend to dwarf the people in them—there are plenty of shots in which the sky takes up more than half the frame—and they bring to mind the Spain-shot Westerns of Sergio Leone, had they been made in black and white and in the Academy ratio. The sense of pastiche is underscored by how this sequence transitions into a color, widescreen story in contemporary South Dakota.

Here, Mastroianni appears again, as herself, in town to shoot a Western. But there’s not a whole lot of drama in the contemporary world. A television weather woman gives a forecast for a region “where our beautiful native community resides;” that one phrase encapsulates centuries of condescension. In that region, a dedicated but clearly exhausted Indigenous cop deals with drug-addicted natives living in squalor while her niece practices free throws and seeks some kind of higher ground.

Alonso’s sense of verisimilitude abuts the potential for viewer alienation something fierce. There’s a poignant visual beauty in a long-held shot of the cop, played by Alaina Clifford, sitting in her parked vehicle looking out her window as a woman in custody, sitting behind her, endlessly whines about her cuffs being too tight and needing to use the bathroom. A drawn-out prison visit sequence, determinedly snail-paced, gets under one’s skin but not necessarily in a purposeful way.

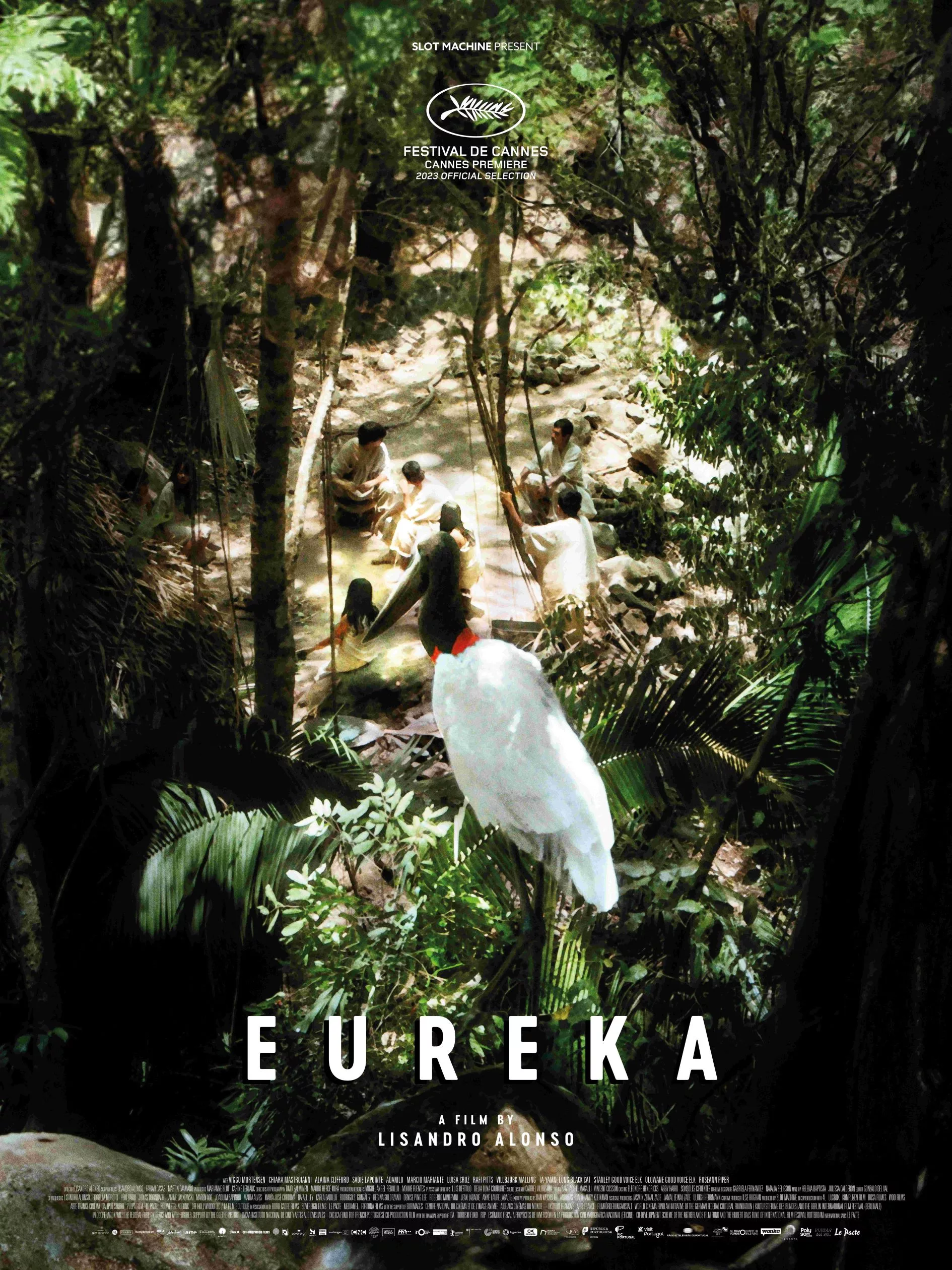

An hour and a half into the movie, our possible title character appears. She’s a bird—a heron-like creature who flies past an earthwork sculpture and into the dissolve that shows a forest and a mountain range. This leads into the final sequence, set among a different group of Indigenous people, those residing in South America. This is a bit more plot-driven than the center sequence, taking a grim, crime-thriller-with-mysticism turn.

A stark shot of a crunched Pepsi can be tossed into an otherwise pristine mountain stream, an image both on the nose and visually powerful, encapsulates the quiet indignation of the filmmaker’s perspective.