Let’s be sure we have this right. The Baja 1000 is the world’s longest non-stop point-to-point race. It has more than a dozen categories of vehicles, from $2 million racing cars to motorcycles to unmodified pre-1982 VW Beetles. The course changes every year. You can leave the course and take a shortcut, but that way you might miss one of the secret checkpoints. The race includes both dirt back roads and Mexican highways. The highways are not blocked to civilian traffic during the event, and the racers have to weave in and out of ordinary traffic. Oh, and they could get stopped by the highway police.

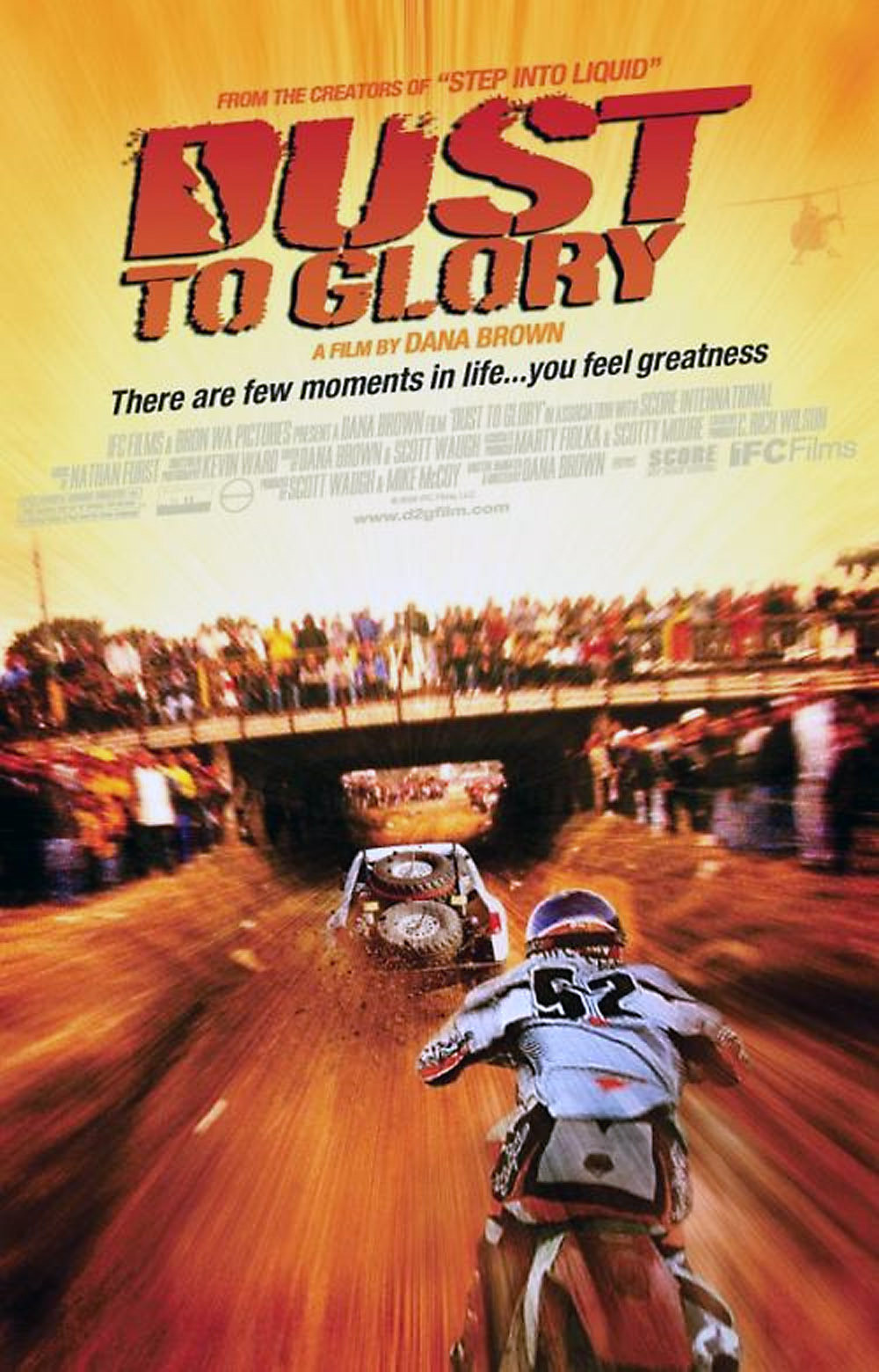

“Dust to Glory” tells the story of the 2003 running of this legendary race, which offers glory but not much money; they can’t even sell tickets, since the fans essentially just walk over to the edge of the road and watch the cars go by. And yet the Baja 1000 attracts stars like Mario Andretti and Parnelli Jones, and, in years past, celebrities like James Garner and Steve McQueen.

The documentary was directed by Dana Brown, son of Bruce (“The Endless Summer“) Brown, who uses some 50 cameras, including lightweight digital cameras mounted on cars and motorcycles. That’s helpful because there is no one place to stand in order to get a good idea of the entire race, especially since each category of vehicle is dispatched separately — the fastest cars, trucks and motorcycles first, the Beetles last. There is a ham radio operator who keeps in touch with the checkpoints, provides weather reports, reports accidents and communicates with the drivers’ support teams, but he looks less like Command Central than like a guy in a hut on a hill with some stuff from Radio Shack.

The record time for the race is 16 hours. There is a winner in every category. You have to finish in 32 hours, and in this race, to finish at all is a victory. Most of the teams have two or three drivers, but the movie’s star (maybe because he is also the co-producer) is Mike “Mouse” McCoy, a motorcycle racing legend who plans to drive solo, nonstop, for all 1,000 miles.

Since the race runs through the night and passes areas where fine silt makes a dust cloud that limits visibility, this is a dangerous thing to do, but then the Baja 1000 is dangerous, anyway: Not least for the spectators, who seem to stand awfully close to hairpin turns where vehicles can spin out. Miraculously, only one person was killed in 2003 — a spectator hit by a motorcycle belonging, not to a racer, but to another spectator, who was driving the wrong way on the course.

There is a kind of madness involved in a race like this, and that’s apparently its appeal. Car companies like Porsche invest big money in their teams, despite the lack of a purse or even much TV coverage (how could ESPN spot cameras along all 1000 miles, and how would they make sense of the countless categories?). The race is more like a private poker game held upstairs in somebody’s suite during the World Series of Poker.

Does Mouse make it? I would not dream of telling you. I will, however, tell you that he has a camera on his motorcycle that records with a sickening thud an accident he has 60 miles from the finish line, during which he injures or breaks (he isn’t sure) some ribs, a shoulder, and a finger.