“Dragon Inn” (1967), a genre classic that has been often-imitated and directly remade twice, is to the martial arts genre what “Stagecoach” is to the Western. Writer/director King Hu (“A Touch of Zen”) made “Dragon Inn” right after he completed “Come Drink With Me,” an equally thrilling and essential 1966 action-adventure that would go on to be a major influence on “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.” Hu cherry-picked some elements from “Come Drink With Me”—particularly from the portion of that earlier film that takes place in a secluded desert tavern—and distilled them to perfection. “Dragon Inn” is such a lean film that you never have to wonder what motivates the characters. It’s an archetypal narrative: the children of a newly-executed Minister of Defense flee to the Dragon Gate Inn, but are met by an army of evil eunuchs, leaving it up to a quartet of heroes to save them from an unjust death. Hu evokes an entire world in his awe-inspiring wide-angle camerawork and graceful, still-unpredictable action scenes. Now modern viewers can enjoy “Dragon Inn” in a new 4K restoration that makes Hu’s classic look appropriately majestic.

The first few minutes of “Dragon Inn” drop a lot of heavy but ultimately negligible backstory on viewers’ heads. So, the short-short version: an evil group of eunuchs have come to power in the year 1457, and they rule with two underling espionage organizations: the Imperial Guards and the East Espionage Chamber. They want to kill the children of a recently executed Minister, so they wait to intercept them at the Dragon Gate Inn. But innkeeper Wu Ning (Cao Jian)—a former ally of the deceased Minister—is allied with wandering swordsman Xiao (Shi Jun), who, along with siblings Hui Zhu (Shangguan Linfeng) and her brother Ji Zhu (Xue Han), protects the Minister’s children.

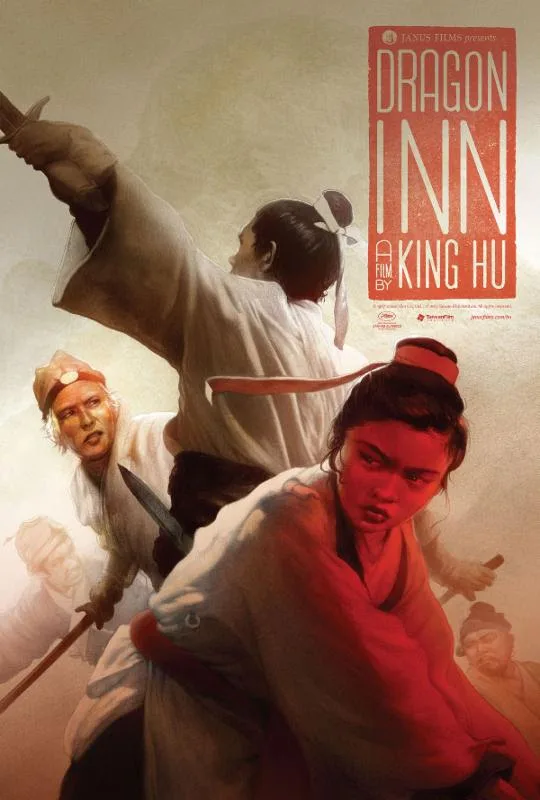

Much of “Dragon Inn” consequently takes place waiting inside the title location. We wait for all of the assembled characters to gather without knowing who will arrive, or when to expect them. Still, each of the main players is treated to several major scenes. “Dragon Inn” is, after all, a fairly democratic ensemble piece. Even villains like Cao Shaoqin (Bai Ying), the leader of the eunuchs, holds his own during the film’s climax. Still, some of the chief pleasures of watching “Dragon Inn” come from watching characters define themselves through action. Even Hui Zhu and her brother get several scenes to show off why they’re more than just supporting characters. This is a film where heroes sacrifice their lives and egos for a cause, and antiheroes and villains are never more attractive than white-hat-wearing good guys.

“Dragon Inn” is a romantic action film, but it still feels modern thanks to Hu’s strict focus on action. I don’t just mean the film’s relentless series of fight scenes. Hu’s film is all about movement. Even the film’s dizzying preface feels like a whirlwind of information compared to the introductory info dumps that precede modern period films. Hu’s tracking shots are so seductive because he wants viewers to feel like they’re traveling with his characters. We are in the middle of the action, which leads to some of the most memorable confrontations in martial arts cinema, like the bit where evil eunuch Pi Shaoting (Miao Tian) tries to intimidate Xiao by trying to take his bowl of noodles away from him, and Xiao casually tosses the bowl from one table to the next. It’s a surprising moment: in one smooth movement, Xiao reveals his nature as a happy-go-lucky, master-less swordsman.

But, ahh, the film’s action scenes! Violence in “Dragon Inn” is exciting not just because it’s choreographed exceptionally well, but because there’s a genuine sense of danger and excitement in each fight scenes. Xiao and his colleagues are completely outnumbered, and it sometimes requires more than one hero to dispatch a single villain. Still, fight scenes in “Dragon Inn” perfectly evoke a philosophy of martial arts that Bruce Lee later espoused in “Enter the Dragon:” “A good fight should be like a small play, but played seriously. A good martial artist does not become tense, but ready.” Heroes leap, pivot and run out of harm’s way because they spend most of any fight anticipating their opponents’ moves. The good guys’ accordingly often react to the their adversaries’ moves, and as a result, gauge the speed and style of their movements. Fighting isn’t just a source of spectacle in “Dragonn Inn,” but rather a central judge of character.