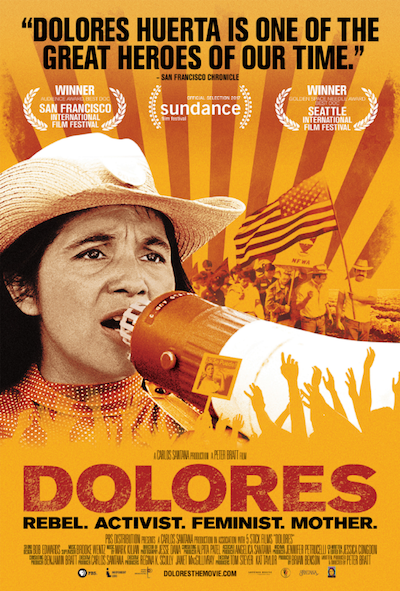

The United States is not a country especially fond of labor leaders, but Cesar Chavez, who organized Mexican-American farm workers and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, still managed to make his way into public school history textbooks. His partner in that enterprise, Dolores Huerta, has largely escaped mainstream attention, and Peter Bratt’s documentary “Dolores” argues that it’s mainly because of a streak of sexism that affects every area of history across the political spectrum.

Huerta, who is 87 and still active and lucid, is her own most persuasive onscreen witness, but there are many others as well. The film tells her story in a plainspoken style that befits the subject. It’s also a primer in how a political figure’s private life can become the focus of attacks when attempts to derail her message aren’t making headway.

Huerta was a star in the labor movement from an early age. By the time she was 25, she had written legislation as part of California’s Community Service Organization. Before she turned thirty, she had co-founded the Agricultural Workers Association with Chavez, the organization that ultimately changed its name to United Farm Workers. Huerta. Chavez’s efforts to organize American farm workers was opposed at every turn and on every level of white dominated society.

One of the film’s more provocative aspects is the way it links U.S. opposition to labor organizations with the legacy of slavery, linking the treatment of predominantly Mexican-American farm workers in California to the plight of African-Americans from Reconstruction to the present. In an arrangement reminiscent of slave plantations and post-Civil War sharecropping, many of them lived with their extended families on property that they served while performing stoop labor for basement wages. As older veterans of early twentieth century farm labor tell the filmmaker, physical and even sexual abuse were rampant on some of these farms. Daily harassment, racist behavior and an overall climate of cruelty were commonplace even on properties that were considered relatively civilized. Workers were afraid to object, fearing not only that they would be fired and ejected from the property but that their extended families would be kicked out, too, to cement the message that under capitalism, the only punishable sin is saying no to the boss.

A contemporary of Huerta’s says that for many decades, workers expected “that we will not see national union in our lifetime because the growers are too wealthy, too powerful and too racist.” Huerta, Chavez and other organizers helped change that, although, as the movie points out, the situation for farm workers remains troublesome to this day.

Huerta’s progress within the labor movement was hampered by the macho temperament of the movement, a predicament that many figures in American labor, and throughout political movements around the world, have described as a constant throughout history. Many of the most headline-grabbing tactics of the movement were Huerta’s doing, and as she became more famous and comfortable, she made sure to live in the same poor communities that she served, to blunt criticisms that she had no connection to them or was only in it for her own enrichment. Yet she never got the credit she deserved, and Chavez himself became irritated by her refusal to take a backseat while he served as the public face of the movement.

Enemies of Huerta seized on her private life to discredit her: she had two divorces, had eleven children by three men, and was frequently absent from her household because of her organizing duties, biographical facts that were used to tar her as someone who advocated corporate responsibility while conducting her own affairs in a heedless manner. Similar accusations are rarely made against men whose domestic lives are a trainwreck, or who have made the decision to put their work first. More recently, Huerta was banned from some college campus speaking engagements after saying that, as a party, Republicans are reflexively racist toward Latinos, a statement she has never retracted.

Huerta has remained, publicly at least, impervious to any slings and arrows that have come her way. In both past and present interviews, she comes off as a smiling steamroller of a woman, rolling forward no matter what obstacles are placed in her path. She doesn’t seem particularly troubled by anyone’s opinion of her as a political figure or a private individual. While viewers will inevitably bring their own world view to bear on her life and work, Huerta’s obstinate nature makes her a compelling movie heroine, in the vein of countless male rebel figures who don’t care if you like them as long as you’re hearing what they have to say. There’s no special filmmaking excitement on display here—the storytelling is orderly to a fault, and Bratt sprints through certain moments, presumably in the interest of pacing, that might’ve benefited from more careful consideration—but Huerta is such a commanding figure, and the array of historical footage marshalled on behalf of her story is so impressive, that the film makes a strong impression.