There’s a point midway in “Dog Day Afternoon” when a bank’s head teller, held hostage by two very nervous stick-up men, is out in the street with a chance to escape. The cops tell her to run. But, no, she goes back inside the bank with the other tellers, proudly explaining, “My place is with my girls.” What she means is that her place is at the center of live TV coverage inspired by the robbery. She’s enjoying it.

Criminals become celebrities because their crimes provide fodder for the media. Many of the fashionable new crimes — hijacking, taking hostages — are committed primarily as publicity stunts. And a complex relationship grows up among the criminals, their victims, the police, and the press. Knowing they’re on TV, hostages comb their hair and killers say the things they’ve learned on the evening news.

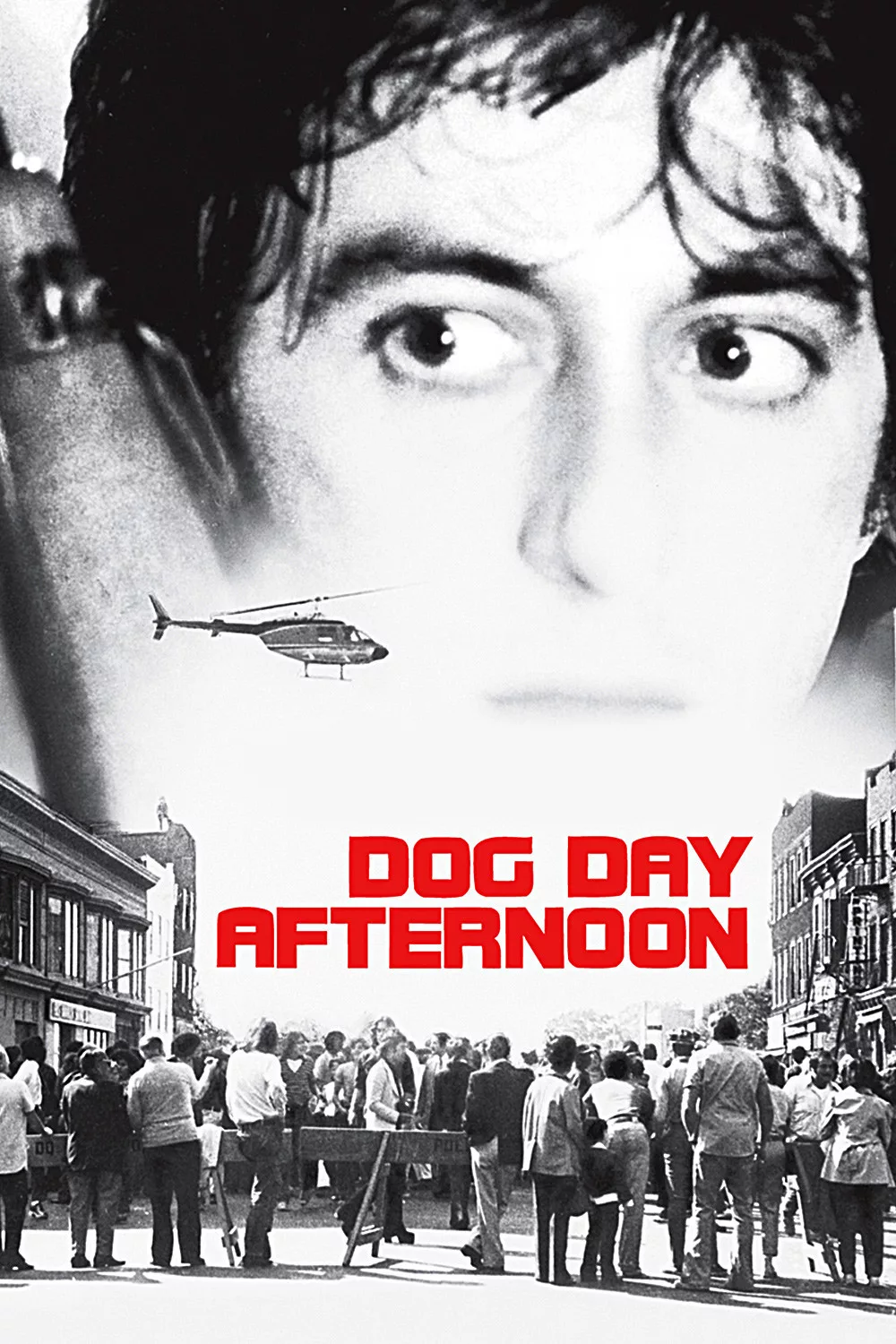

That’s the subject, in a way, of Sidney Lumet’s pointed film. It’s based on an actual bank robbery that took place in New York in the 1970s. And it seems to borrow, too, from that curious episode in Stockholm when hostages, barricaded in a bank vault with would-be robbers, began to identify with their captors. The presence of reporters and live TV cameras changed the nature of those events, helped to dictate them, made them into happenings with their own internal logic.

But Lumet’s film is also a study of a fascinating character: Sonny, the bank robber who takes charge, played by Al Pacino as a compulsive and most complex man. He’s street-smart, he fought in Vietnam, he’s running the stick-up in order to get money for his homosexual lover to have a sex-change operation. He’s also married to a chubby and shrill woman with three kids, and he has a terrifically possessive mother (the Freudianism gets a little thick at times). Sonny isn’t explained or analyzed — just presented. He becomes one of the most interesting modern movie characters, ranking with Gene Hackman’s eavesdropper in “The Conversation” and Jack Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea in “Five Easy Pieces.”

Sonny and his zombie-like partner, Sal, hit the bank at closing time (a third confederate gets cold feet and leaves early). The stick-up is discovered, the bank is surrounded, the live TV mini-cams line up across the street, and Sonny is in the position, inadvertently, of having taken hostages. Sal (John Cazale) is very willing to shoot them, a factor in all that follows.

There are moments when “Dog Day Afternoon” comes dangerously close to the clichés of old Pat O’Brien gangster movies and the great Lenny Bruce routine inspired by them (the Irish cop shouts into his bullhorn “Come on out, Sonny, and nobody’s gonna get hurt,” and Sonny’s mother pleads with him from the middle of the street). But Lumet is exploring the clichés, not just using them. And he has a good feel for the big-city crowd that’s quickly drawn to the action. At first, Sonny is their hero, and he does a defiant dance in front of the bank, looking like a rock star playing to his fans. When it becomes known that Sonny’s bisexual, the crowd turns against him. But within a short time (New York being New York), gay libbers turn up to cheer him on.

The movie has an irreverent, quirky sense of humor, and we get some notion of the times we live in when the bank starts getting obscene phone calls — and the giggling tellers breathe heavily into the receiver. There’s also, in a film that’s probably about fifteen minutes too long, an attempt to take a documentary look at the ways police and banks try to handle situations like this. And through it all there’s that tantalizing attraction of instant celebrityhood, caught for an instant when a pizza deliveryman waves at the cameras and shouts, “Hey, I’m a star!”