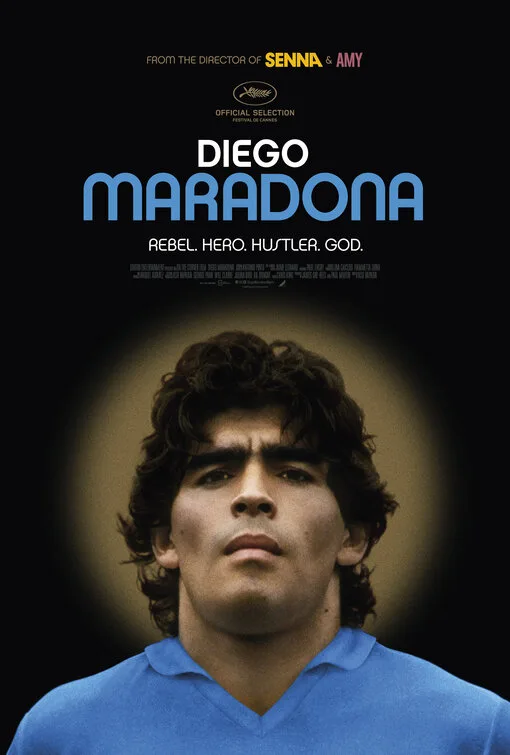

Fernando Signorini, the man who trained soccer superstar Diego Armando Maradona, tells us that there were two different men inside this now-legendary player. There was Diego, sweet, insecure, someone Signorini says he would do anything for. And then there was Maradona, an invented character, confident to the point of arrogance. Him, Signorini tells us, he would not waste time on. The problem is that it is Maradona who made near-miraculous goals, Maradona who was welcomed to his new team by 85,000 cheering Neapolitans, Maradona whose photograph was hung in homes throughout Naples, usually next to the picture of Jesus. We meet Diego the man in this film, but without Maradona the athlete, there would not be a documentary about either side of him.

Those divided selves are the real focus of this film, which has sparing voice-over narration and lets us learn the story through observing Maradona himself, his unguarded face more eloquent than any commentary. My father says that each of us has three selves: how we want others to see us, how they do see us, and how we really are. And he explains that the more integrated those three selves are, the happier, stronger and more grounded we will be. Maradona, who was as good as it is possible to be in scoring points in soccer games, wanted to be everything the people around him wanted him to be, a beloved cultural hero, a devoted family man, a sophisticated gentleman about town who was befriended by the local mobsters. He wanted to have some fun, blow off steam and get help with the pain from his sports-related injuries. And so, his selves became more and more splintered.

In fact, this intimate film culled from over 500 hours of archival footage shows us at least five sides of the Argentine-born Maradona, who was born to a poor family in a shanty town outside of Buenos Aires. We see the devoted son who supported his family since he was a teenager, who saw soccer as a way to give them a comfortable life. We see the astonishingly gifted athlete, combining speed, power, coordination, lightning reflexes, a strategic understanding of what it took to get the ball where it needed to be, and the ability to inspire his teammates to do their best. We see the poor kid with no education facing the scrutiny of constant, intense attention from fans, press, and competitors. We see that same poor kid suddenly wealthy, famous, and surrounded by every kind of temptation—sex, drugs, and a very powerful crime family known as the Camorra. And we see the struggle for identity, the loving father who denies paternity of his son, the team player who returns to his Argentinian roots to play in the World Cup and finds himself playing against his new countrymen in their home court. As they used to say on The Wide World of Sports, Maradona responds to both the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.

He was just so good. The footage of Maradona’s early years shows his extraordinary power in racing down the field and extraordinary delicacy in handling the ball (do you say footing if hands are not allowed?). Speaking of handling, the film is frank about one goal that should have been declared a foul because his hand was clearly involved. But if the refs and even the opposing team were so dazzled by him that they let it go, we can understand.

Director Asif Kapadia, who also made the Ayrton Senna and Amy Winehouse documentaries, lets the familiar story of a gifted kid who follows early success with fame and then tragedy unfold. But he asks us to think about ourselves as well. Why do exceptional people matter so much to us? Why do we get so emotionally attached to a team? Is it fair to expect them to be not just talented but honorable and heroic? One of the critical turning points for Maradona was in the World Cup, when he was playing for the country of his birth, against the country of the team that bought him. There is one kick that will prove to the crowd which side he is really on. It is not in him to do anything but give his best to win. Kapadia’s film shows us that for better or worse, Maradona’s loyalty was always to the game, and that, as much as his skill on the field, deserved more loyalty from the fans.