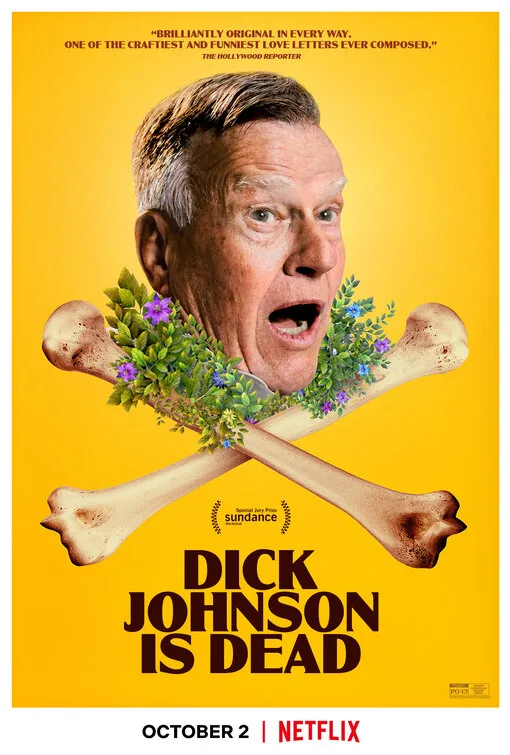

Dick Johnson dies in “Dick Johnson is Dead.” He dies over and over and over again, courtesy of his filmmaker daughter, Kirsten Johnson, who made this documentary to come to terms with his eventual death, her own, and everyone’s.

The deaths of Dick Johnson—or “deaths”—are staged for maximum mayhem, sadness, or surreality. Dick dies getting hit on the head by a falling air conditioner, by a car, by having blood spurt from his neck. Sometimes the deaths just suddenly happen. Other times they’re telegraphed well in advance, by showing Kirsten and Dick in conversation with, say, a stuntman who will impersonate Dick falling on a sidewalk, or a woman hired to stage the artery-spurting death by hiding a vial of stage blood under Dick’s jacket and pumping it offscreen when Kirsten gives the cue. There are also lighthearted, even inspirational fantasy visions, as when Kirsten puts her dad in a tableau of Jesus anointing and healing his two malformed feet.

What’s going on here? A lot of things. If one were to look at this film as a psychologist might—and why not, since Dick Johnson is a psychologist?—one might see the death scenes as a means of exercising control over an uncontrollable eventuality (Kirsten gives her father visually ravishing demises, befitting a hero of song and legend, and many ordinary ones). One might also interpret the death scenes as a roundabout, self-deprecating way of admitting that neither father no daughter can control Dick Johnson’s death, or any death, except in small ways.

These scenes also feel like a warm, willed form of regression. We see Dick, a cheerful and agreeable man, engaged in imaginative play with his young grandchildren—pushing them on swings, falling down with them, leading them in singalongs (“I’m Popeye the sailor man/I live in a garbage can!”). What he’s doing with Kirsten is a more elaborate, adult version of that, with a crew and a budget—rather like a moment late in the film on a beach in Lisbon, where the grandchildren partly bury their grandfather in sand (he’s laid out on his back, arms folded across his chest) and he “awakens” and growls at them like a slumbering beast and tries to rise up.

More significant, ultimately—and more poignant, because they’re ordinary—are the scenes where Kirsten hangs back and observes her father as he goes about his life: eating at a breakfast table, sitting behind his desk at his office in Seattle, contemplating the house where he and his late wife lived before he’s about to move to New York to spend the rest of his life with Kristen, who’s going to take care of him. Dick has to move. He can’t take care of himself anymore. He has Alzheimers’ disease, and it’s accelerating: he’s been double-booking patients, and was reported for driving at high-speed through a construction zone (fortunately, no one was hurt).

This is another recurring subject: memory and the loss of it, either via the inexorable forward march of time (even people with great memories can’t remember everything) or dementia. By committing to spending even more time with her dad, and filming him in both mundane and fantastic situations, Kirsten is preserving and creating additional memories that she’ll have on film even after her father is gone.

But are some of these new memories more meaningful or authentic than others? And how much consent, realistically, can Dick give at this point? The movie courts audience disapproval in the scenes where Kirsten uses her dad as a leading man in her death fantasies. He adores and respects his artist daughter and is gung-ho to participate in anything. But there are moments where it’s obvious that he doesn’t fully grasp what’s happening (he misunderstands the blood bag stunt and thinks it’s his blood, not stage blood, in the bag).

Kirsten seems aware of this problematic aspect as well. “I just have to be careful about not overstepping the bounds of what’s decent for him,” she tells a nurse who doesn’t seem all that approving of all of this filming. But the fact that it isn’t foregrounded as much as all her other big themes and subjects suggests that this a rare instance of an otherwise fearless director (at least partly) evading a tough question. (She addresses it more fully in press interviews outside of the context of the film. “I wish him to die; I don’t wish him to die,” she told Helen Shaw of Vulture. “Am I exploiting him with this film? Am I giving him immortality?”)

Still, this is a rich and rewarding documentary that feels like the next stage in the stylistic evolution of Kirsten Johnson. She spent decades shooting other people’s movies (deadly serious documentaries on war, deprivation, and misogyny) before producing one of the greatest and most innovative nonfiction films of the past decade, 2016’s “Cameraperson.” Where that movie rigorously avoided any sort of narrative handholding—instead creating several overlapping implied narratives through careful arrangement of footage that the director shot for others—this one feels more traditional in the telling (the staged deaths notwithstanding).

But the process of filmmaking—of storytelling generally—is foregrounded here as well, though in a more direct and playful manner. We don’t just see “deaths” being planned, rehearsed and shot; we also see father and daughter in conversation about what it means to film and be filmed. There’s even a scene where one of the film’s occasional bits of voice-over starts on the soundtrack over unrelated images, then the movie cuts to Kirsten in a closet, filming herself recording the narration that you’ve been listening to.

The result feels traditional and radical at the same time. And even its cheekiest flourishes are inviting because “Dick Johnson is Dead” is suffused with intense, reciprocated love—not just by father and daughter, but by Dick and Kirsten and their friends, and by Kirsten and fellow director Ira Sachs and his husband Ben Torres, the dads of the twins she had via artificial insemination in 2008.

Another sort of love—ghostly, vestigial perhaps, yet present—is the love that the subjects feel for people who aren’t there anymore, chiefly Dick’s wife and the director’s mother, who also had dementia. We also hear through Kirsten that her mother lost her own mother at a young age, in a car crash caused by a drunk driver. Dick’s mother also died young. To be alive is to lose people.

“It would be so easy if loving only gave us the beautiful,” Kirsten says in voice-over. “But what loving demands is that we face the fear of losing each other.”

The movie allows for the possibility that all of this—the death scenes, the move from Seattle to New York, the acceptance of responsibility for another person’s life, the metafictional touches, the act of filmmaking itself—is simultaneously a method of infusing an otherwise chaotic and random existence with meaning and beauty, and another set of activities that are undertaken mainly to distract the participants from obsessing about the ends of their own stories.

Maybe “Dick Johnson is Dead” is the filmmaking equivalent of the band on the deck of the Titanic playing their hearts out while the water rises. If so, the movie is aware that it might be that thing, and seems content to be that thing. That’s every movie, every story. When the end is preordained, you might as well make music.