Not long before Election Day 2008, the president of the United States is making a campaign tour through Colorado when a sudden snowstorm traps him in a roadside diner. Alarming news arrives: Saddam Hussein’s son has sent Iraqi troops into Kuwait, and 80 percent of America’s troops are far away, committed in the Sea of Japan. What to do? Drop the Bomb, obviously.

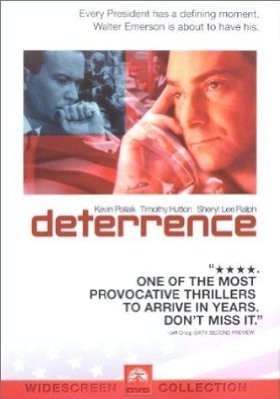

Or at least threaten to. That’s the strategic tactic tried by President Walter Emerson, played by Kevin Pollak as a man who wasn’t elected to the highest office but got there through a combination of unforeseen events. He doesn’t look very presidential and he’s not terrifically popular with the voters, but the office makes the man, they say, and Emerson rises to the occasion with terrifying certitude: Yes, he is quite prepared to drop the first nuclear weapon since Nagasaki.

This story unfolds in a classic closed-room scenario. The storm rages outside, no one can come or go, and the customers and staff who were already in the diner get a front-row seat for the most momentous decision in modern times. Although the president cannot move because of the weather, he can communicate, and he negotiates by telephone and speaks to the nation via a camera from the cable news crew that’s following him around.

Watching the film, I found a curious thing happening. My awareness of the artifice dropped away and the film began working on me. The situation, it is true, has been contrived out of the cliches of doomsday fiction. The human relationships inside the diner are telegraphed with broad strokes (and besides, wouldn’t the Secret Service clear the room of onlookers while the president was conducting secret negotiations with heads of state?). There is a ludicrous moment when the president steps outside into the storm with his advisers to tell them something we’re not allowed to hear. And the ending is more or less inexcusable.

And yet the film works. It really does. I got caught up in the global chess game, in the bluffing and the dares, the dangerous strategy of using nuclear blackmail against a fanatic who might call the bluff. With one set and low-rent props (is that an ordinary laptop inside the nuclear briefcase “football?”), “Deterrence” manufactures real suspense and considers real issues.

The movie was written and directed by Rod Lurie, the sometime film critic of Los Angeles magazine. On the basis of this debut, he can give up the day job. He knows how to direct, although he could learn more about rewriting. What saves him from the screenplay’s implausibilities and dubious manipulation is the strength of the performances.

Kevin Pollak makes a curiously convincing third-string president–a man not elected to the office, but determined to fill it. He is a Jew, which complicates his Middle East negotiations and produces a priceless theological discussion with the waitress (Clotilde Courau). He is advised by his chief of staff (Timothy Hutton) and his national security adviser (Sheryl Lee Ralph), who are appalled by his nuclear brinkmanship and who are both completely convincing in their roles. The screenplay gives them dialogue of substance; the situation may be contrived, but we’re absorbed in the urgent debate that it inspires.

I mentioned the ending. I will offer no hints, except to say that it raises more questions than it answers–questions not just about the president’s decisions, but about the screenwriter’s sanity. “Deterrence” is the kind of movie that leaves you with fundamental objections. But that’s after it’s over. While it’s playing, it’s surprisingly good.