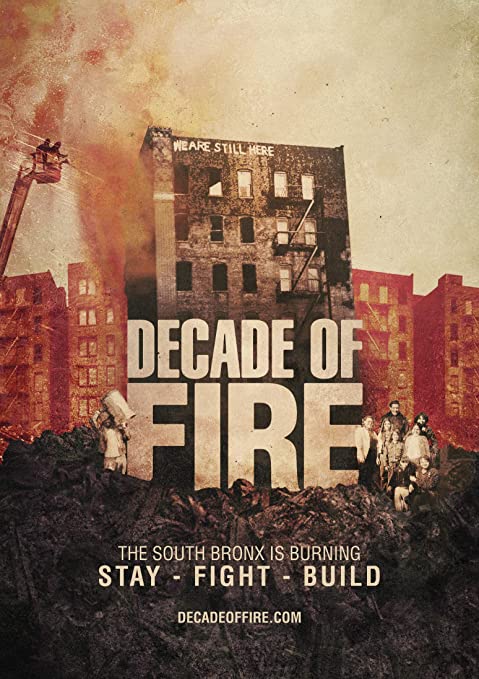

Americans of a certain age will remember the images of the Bronx in ruins. Throughout the 1970s, the New York City borough was thought of as the epicenter of urban decay: a wasteland of rubble piles, vacant lots, and decaying apartment buildings where law-abiding citizens eked out a desperate living while trying to avoid contact with roving gangs of drug dealers and stone killers. This perception of the Bronx was carried to the rest of the country, and the world, through media images, and soon found its way into popular culture. All you have to do to see cause-and-effect is go to a search engine, type in “Bronx” and see what comes up. Crime films, action pictures, apocalyptic science fiction flicks, and vigilante fantasies, mainly. Nobody ever made a film with a title like “The Bronx: A Love Story.” Or if they tried, audiences never saw it.

Vivian Vázquez Irizarry, the co-director, narrator, and central character of “Decade of Fire,” offers a rare, different view of her home. She grew up in the Bronx in the 1970s and remembers what it was like there before the wave of fires began. Irizarry and her family and neighbors are still angry about what happened there. It was already hard for the area’s residents—mainly Black and Latinx families, ranging in income from working class to poor—to survive day-to-day in the first place, thanks to “redlining” (a racially discriminatory, though “unofficial,” policy of rarely giving business and personal loans to poor, mostly minority people).

But in the 1970s, things got even worse. Callous landlords figured out that it was more profitable to let apartment buildings decay instead of repairing them, then hire local teenagers—many of whom were already in a nihilistic, angry frame of mind, due to racism and the lack of job opportunities—to set fires that would damage the structures beyond repair, resulting in insurance payouts. The structures were thought of as cash boxes that could be opened by lighting a match. The fates of the people who lived there—some of whom were injured or killed in the blazes—were not important.

Then came the ultimate indignity: the fires were blamed completely on the residents. The country’s white-dominated media—which at that point was targeted mainly at suburban homeowners, and confirmed any racist attitudes they held—continually reinforced the same message: These people burned down their own homes. Therefore, there was no reason to care about them, or even investigate the agreed-upon narrative, because they and their neighborhood weren’t worth caring about.

Vázquez Irizarry begins the story with a nostalgic, tender evocation of the pre-fire Bronx—a place with a vibrant street culture, distinguished by the smell of delectable food being cooked in homes and restaurant kitchens, and the sounds of radios and local musicians spilling from open doorways and windows in summer. Then she and co-director Gretchen Hildebran contextualize what came next, explaining the economic practices and racial attitudes that set the stage for what would eventually be revealed as ritualized arson.

The film isn’t without its problems—Irizarry’s writerly narration is often ill-served by her own, rather flat delivery, and there are some problems balancing all the historical/academic background with personal experience. But it’s ultimately an affecting, at times overwhelming experience, because of the sheer volume of emotion it generates by pointing cameras at real people and having them tell stories of the two Bronxes they remember, from before the fires and after. Cinematographer Edwin Martinez’s interviews and present-day location shots give the movie a distinctive look that matches the copious TV news footage deployed as backup for the citizens’ remembrances: soft, compassionate, at times slightly hazy, as if the film itself is still traumatized even when remembering good times. (That the filmmakers have taken the trouble, whenever possible, to track down source footage from 1970s TV news, which was shot on 16mm film, rather than just grabbing things from YouTube, further enriches the story: we’re not as distanced from what’s happening because the past and present have a similar richness of texture.)

More than anything else, though, “Decade of Fire” succeeds as one of the best explanations in recent cinema of what the phrase “systemic racism” means. The warped values of the people who burned the Bronx, after many years of neglecting and undermining the people who lived there, are projected onto their victims, excusing the crimes committed against them by implying that it’s no big deal because the place and its people weren’t worth saving anyway. It’s victim blaming on a grand scale.

There’s also an innate power to the many scenes where the filmmakers just plant a couple of cameras in a room and let people talk about their lives, in the process recounting stories that American cinema rarely tells. The movie is as much a reclamation or restoration project as an expose. The filmmakers are trying, through testimony and compassion, to resurrect murdered neighborhoods—and insist, decades later, on the innate value of stories that the dominant culture didn’t think was worth acknowledging at the time.