The responsibilities of the United States Supreme Court come from the Constitution. The Founding Fathers who dreamed up the checks and balances between the executive (President and Cabinet agencies), the legislative (Congress and the Senate), and judicial (federal courts) set up an intricate formula for a rock-scissors-paper system of oversight. But the highest court’s authority is only partially based on its Constitutional role. It is the only branch that is not elected by the voters, and it must wait for questions to come to it; its jurisdiction is purely responsive. Alexander Hamilton famously called the judiciary the weakest branch of government because it “has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither force nor will, but merely judgment.”

So, what happens when that judgment comes into question? The Supreme Court’s authority is dependent on its mystique. Its home is a “marble palace” behind the Capitol building. It operates in what it might call a cocoon of confidentiality but what the rest of the world might call a lack of transparency. The oral arguments are open to the public, meaning those lucky enough to get seats in the Court to watch in person; there are no C-SPAN cameras. The Court’s decisions have often been controversial, but it is only recently that questions have been raised about its legitimacy, due to the politicization of the appointments process and exposes about conflicts of interest and abandonment of the most fundamental principles of jurisprudence.

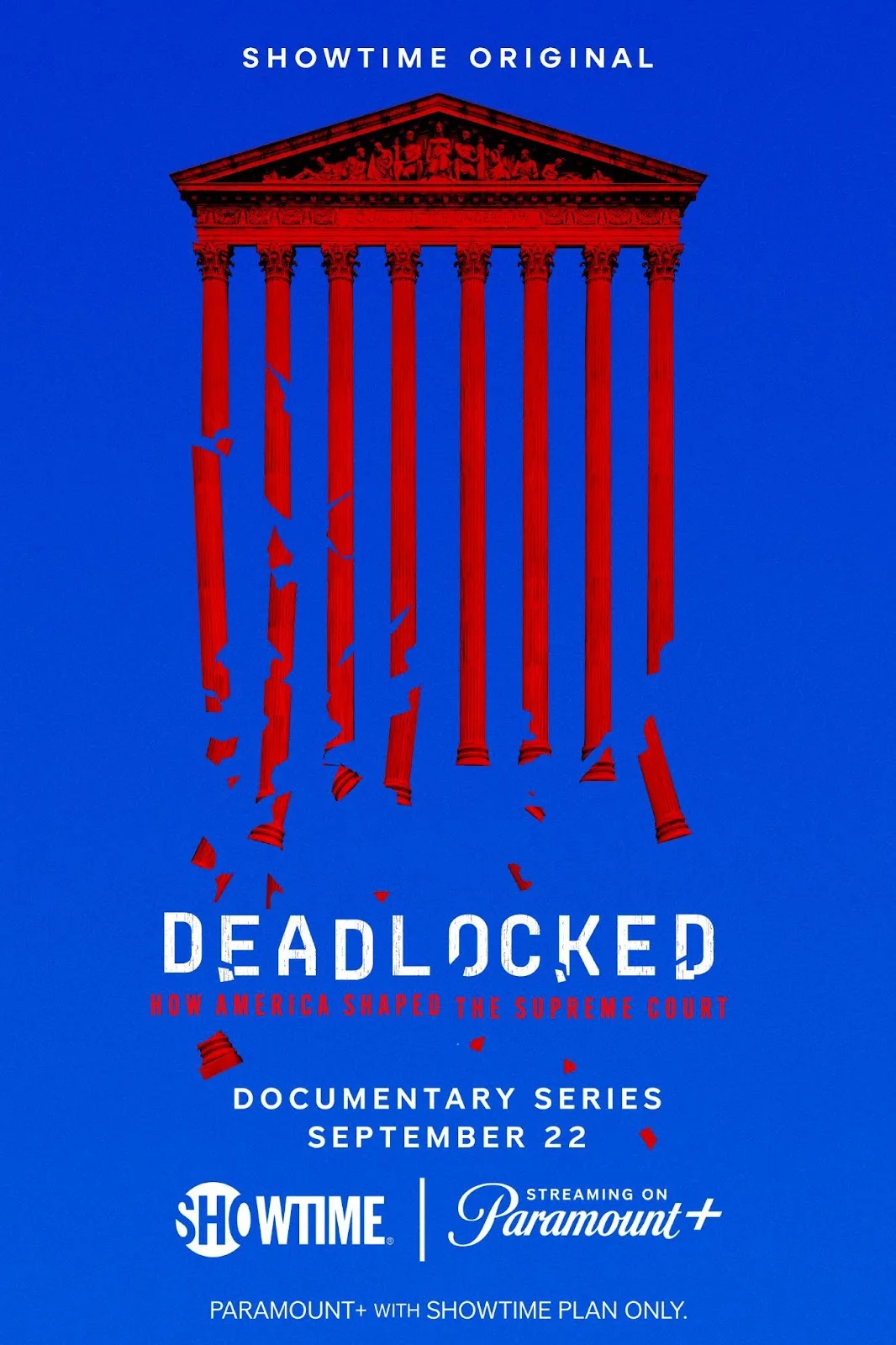

That is the subject of Dawn Porter’s four-part series called “Deadlocked: How America Shaped the Supreme Court.” The pointed subtitle lets us know that this is not the story of how the Court shaped the country, as it might have been if it was made in the 1970s.

Porter is also the director of “Trapped,” the excellent documentary about the anti-abortion laws lined up in majority-Republican states to go into effect if Roe was overturned, and the outstanding “Lady Bird Diaries,” based on the audio journal kept by the First Lady.

This film is more like a follow-up to Susan Saladoff’s “Hot Coffee,” the documentary about the decades-long project to remake the courts at the state and federal level so they would make more rulings in favor of corporations and wealthy people and fewer in favor of consumers, middle class families, and those below the poverty line. What that film made clear was that there was a very focused, very well-financed effort to influence the courts, following a series of culture-shaking Supreme Court rulings desegregating schools, formalizing the rights of criminal defendants, and basing individual privacy rights in the “penumbras” (implications) of the Constitution that led to rulings in favor of birth control, inter-racial marriage, and abortion rights.

“Deadlocked” is a straightforward, moderate depiction of the Supreme Court from that period to the present. Today’s audiences may be surprised to hear that back in the Eisenhower era, the selection process was both more and less political. More because Eisenhower quietly promised former California governor Earl Warren the Supreme Court seat as thanks for his help in the election, less because of the idea of turning a nominee’s confirmation hearings into a must-watch political battle before the Senate Judiciary Committee. The series takes us through the arrival of each justice and some of the most high-profile decisions. Many of those, like the Miranda warnings for people under arrest and the right to marry someone of a different race, are so ingrained in our culture that it is impossible to imagine they were ever at risk of being decided differently. Others continue to rankle.

Until recently, progressives had a significant advantage. By definition, conservative justices were less likely to overturn precedent. As the series shows, conservatives were disappointed with justices like David Souter and Sandra Day O’Connor, whose decisions they saw as more liberal than they expected. Determined not to let that happen again, the Federalist Society evolved from student-run groups on just two law school campuses to a powerful nationwide organization that has played a dominant role in supporting a new generation of lawyers who were not conservative in traditional terms (supporting a strict interpretation of the Constitution and limited government) but conservative in terms that can be considered radical with new theories and abandonment of principles of interpretation of legislation and precedent that had been in place for two centuries. If you had a drinking game for every time someone in this movie talks about “shattering norms” or “abandoning precedent” or the equivalent, you would be tipsy, which may be the best way to watch the fourth episode about the chaotic, scandal-prone recent years.

The series provides good historical context, showing Nixon as the first President to try to use his appointments to move the Court to the right and his failed nominations of Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell, though it omits one of the wildest sentences in Senate history, Nebraska Senator Roman Hruska’s defense of Carswell, “Even if he is mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers, and they are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they?” Then there was Reagan’s nomination of Robert Bork, a victory for progressives at the time but ultimately a roadmap the Republicans used for the vicious confirmation battles ahead, including Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refusing to give Barack Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland (now the Attorney General) a hearing saying it was too close to the election (almost a year) but pushing through Trump’s third appointment to the Court, Amy Coney Barrett, just days before the election Trump lost to Biden. Like the judges he pushed through, McConnell did not feel bound by precedent or consistency. We also see the sexual abuse allegations for Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh, both ultimately confirmed.

There is a good explanation of the “shadow docket” to circumvent the appeals process. Many cases, some hugely consequential, are decided without full briefing or oral argument and often without written opinion. Over 16 years, Presidents Obama and George W. Bush used the emergency shadow docket eight times. President Trump used it 41 times in four years.

Leading experts provide context and balanced commentary, including Slate’s Dahlia Lithwick, the Washington Post’s Ruth Marcus, Supreme Court litigator Paul Smith, and the University of Chicago’s Geoffrey Stone, my favorite law school professor. But there are a lot of experts, and they are not always identified on repeat appearances, so it’s hard to keep them straight.

The last episode in the series is titled “Crisis of Legitimacy,” with recent revelations about gifts and favors to Justices Thomas and Alito from billionaires and Ginny Thomas’ messages to Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows about challenging the election’s legitimacy. But there is little attention to the most significant factor leading to the Court’s lowest level of public confidence in history.

The Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision opened the floodgates of dark money that was a deciding factor in supporting President Trump’s nominees for the lower courts and the Supreme Court and is a major factor in the Court’s reversal of gun rights and other controversial cases. We see a reference to Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony that Justice Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her when they were in high school, but we do not hear about his refusal to answer questions about who paid off the considerable debts he had before his nomination.

During the Trump administration, one of many shattered norms was eliminating the role of the independent, non-partisan American Bar Association in evaluating the fitness of judicial nominees. We see Leonard Leo and hear about his boomeranging between his role at the Federalist Society and partisan work on behalf of nominees to the Court. But we do not hear about the people funding the Federalist Society, which includes the Koch brothers and other billionaire contributors to extremist groups. The series does not mention that billionaire Barre Seid donated $1.8 billion to Leonard Leo’s efforts to get far-right judges and justices nominated and more to groups promoting climate change denial. The series cites Justice Brennan, who said the most important number for the Court is five (a majority). But today, he might conclude that the most important number is the one with a dollar sign in front of it.

A key moment in the series is a brief section from a respectful debate between Justice Breyer (liberal) and Justice Scalia (conservative). Scalia says that the language of the Constitution is clear and must be followed. Breyer smiles that the language is never clear. Breyer is right about the complex disputes that come to the Supreme Court, which are almost always about the collision of two or more protected rights. The Court refuses to adopt the ethics rules that apply to every other judge, making it harder to trust decisions like those turning the right to personal choices into the right to impose those choices on others. Just as the Warren Court decisions considered radical at the time led to a decades-long political backlash, this may trigger the checks and balances in the Constitution all three branches of government swear to uphold.

The four-part series will make its streaming debut on Paramount+ with SHOWTIME on Friday, September 22, and premiere that day at 8 p.m. ET/PT on SHOWTIME.