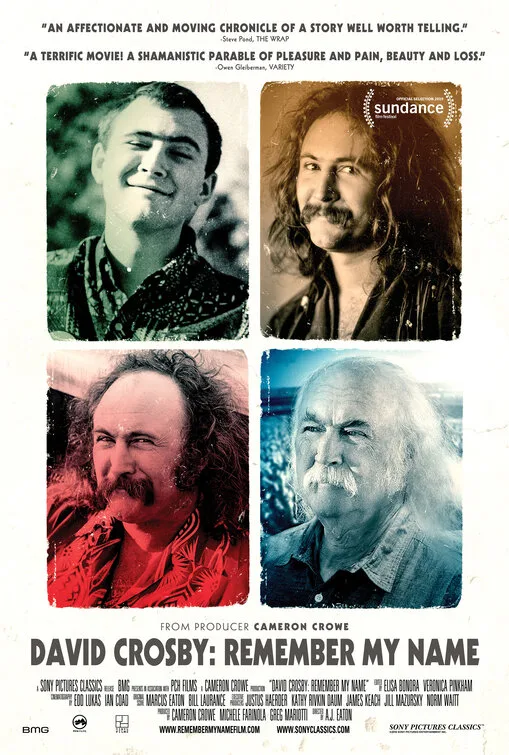

A.J. Eaton’s “David Crosby: Remember My Name” was one of the most acclaimed hits at Sundance this year, and I recall what a critic friend told me about the reaction to the film he saw there. “Millennials seemed to love it,” he said with a note of amazement in his voice.

His surprise was understandable. Viewers too young to remember the ‘60s have spent their lives so inundated with the mythology of that decade that it’s easy to imagine them reacting to any new evocation of it with a reflexive yawn and roll of the eyes. That “David Crosby: Remember My Name” proves to be such a notable exception to that rule owes, I think, to a felicitous paradox: While the documentary does conjure up the whole sex-drugs-rock ’n’ roll ethos of that fabled time with great flair and pungency, it also movingly probes the hazards and costs of the overindulgence and self-deceptions the era’s lures often entailed. In essence, it serves up the myth and a necessary corrective to it simultaneously.

That this blend comes across so powerfully on screen has a lot to do with David Crosby’s complicated charisma. I’ve been interested in—and in many cases, a fan of—Crosby’s work since the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” first hit my teenage eardrums way back when. But if Crosby’s musical gifts were always clear enough, his personality was more muddled, a mix of charm and boorishness, cockiness and annoying self-infatuation. Onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, he embarrassed his fellow Byrds by haranguing the audience with a lengthy spiel about the assassination of President Kennedy. Not long after, Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman fired him from the band because Crosby had become, as McGuinn put it, “insufferable.” (In another recent doc, “Echoes in the Canyon,” Crosby explains his firing by saying simply, with a rueful smile, “I was an asshole.”)

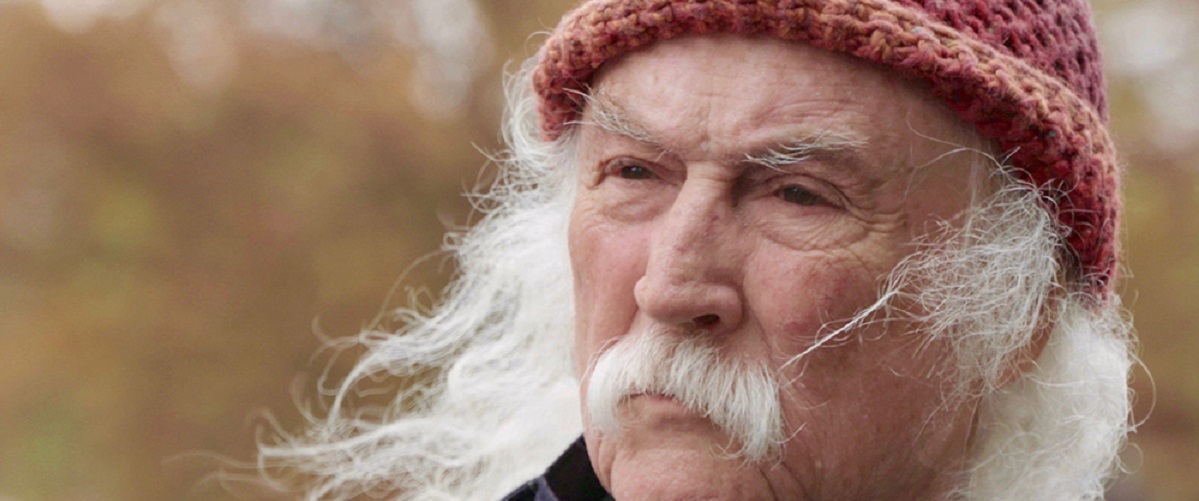

Eaton’s film, which might’ve been titled “The Asshole in Winter,” gives us a Crosby who in many ways is unreformed and unreconstructed, but also, in his late 70s, is reflective enough to be his own harshest critic. And whatever you think of the guy’s character, he is one helluva raconteur. The film is built on a series of interviews, some conducted by Eaton, others by producer Cameron Crowe, who was all of 16 when he first interviewed Crosby for Rolling Stone. These interviews, which were intended to be “brutally honest,” may be the best I’ve ever seen in a rock doc. Partly that’s due to how intelligent and incisive the questions are. But it’s also due to Crosby’s eloquence and willingness to bare his soul to the closest examination.

The son of cinematographer Floyd Crosby, whose credits include “Tabu” and “High Noon,” Crosby was Hollywood-centric from the get-go, and seemed ready for the rush of fame and pop-music innovation that erupted in Los Angeles following the Beatles’ arrival in 1964. Alongside contemporaries like the Beach Boys and the Mamas and the Papas, the Byrds turned out a series of distinctive, groundbreaking hit singles that made them cultural icons and wealthy celebrities in very short order. Crosby’s trademarks, established early on, were his pristine vocal harmonies and unusual guitar tunings.

Not long after his ejection from the Byrds, he was harmonizing one day with friend Stephen Stills, late of Buffalo Springfield, when a visitor from England, Graham Nash of the Hollies, arrived. What happened next became legend: The third time through the song they were singing, Nash added his high harmonies to the other two voices, and, as Crosby recalls, it took about 40 seconds for the three men to realize that they had hit musical gold.

Within months, Crosby, Stills and Nash had a smash debut album and, playing only their second live gig, were one of the hits of the Woodstock music festival. Some hailed them as America’s answer to the Beatles, but of course there was a big difference between the two groups: While the Beatles labored and bonded in early obscurity, CSN came out of the box labeled a “supergroup” and had the super-sized egos to prove it. Once Neil Young was added to the band, the stage was set for a decades-long drama in which strong friendships and creative collaborations were regularly interrupted by fights, recriminations and breakups.

The music, though, sometimes made the turmoil worth it. Our present White House occupant notwithstanding, I don’t think any public event has ever angered me as much as the killing of college students at Kent State in 1970, and hearing Young’s searing anthem “Ohio”—as Crosby angrily points at photos of soldiers who were not indicted for the slayings—again brought tears of rage to my eyes. The disc has been called the greatest protest record ever made.

To turn from the rock ’n’ roll to the sex and drugs, Crosby’s life contained such a superabundance of both that he probably deserves his own entry—make that two entries—in the Guinness Book of World Records. About his numerous hookups and affairs he sounds especially self-critical and regretful, saying that he was selfish and never loved well enough. At least Joni Mitchell, whom he discovered singing in a Miami bar and introduced to the music world, was able to give him a suitable comeuppance, by singing a song that announced their breakup. The woman who seems to preoccupy him most, though, was his girlfriend Christine Hinton, who was killed in a car crash at age 21, leaving Crosby with an emotional wound that still appears to haunt him.

As for the drugs: he did them, and they nearly did him in. The combination of heroin and cocaine made him a hopeless, helpless addict, a bind from which he was released only by a stint in prison in 1986. He supposedly has been clean since then, though his years of high living left him with a host of health problems: he’s had a liver transplant, has eight stents in his heart, etc. Though he now has a happy home life with longtime wife Jan and a bunch of dogs and horses, and recently has had a creative surge working with a group of young musicians, the shadow of mortality hangs over Crosby, and no doubt contributes to the sense in this film that his efforts to get at the truths of his life have a certain urgency to them.

There’s something a bit strange about this ultimately, though. From one angle, “David Crosby: Remember My Name” (the title nods to his great 1971 debut album If Only I Could Remember My Name) has the shape of a tale of redemption: Crosby comes to terms with his life and reconciles with those he’s wronged. But that’s not how it turns out. Near the end of the film, he reveals that none of the guys he’s been closest to creatively—Stills, Nash, Young and McGuinn—will speak to him, due to outrages he’s committed against them, some very recently. What outrages? That the film doesn’t tell us must be counted a flaw. (Those interested in this should consult David Browne’s excellent new book Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.) But it’s virtually the only flaw in a work that is otherwise an exemplary piece of documentary filmmaking.