There’s nothing wrong with clichés, in and of themselves. They can be useful, and most stories utilize them to some degree. The problem with clichés comes when they are used as lazy shorthand. Clichés are already shorthand, so when you shorthand the shorthand, assuming audiences will just take the leap into whatever “reality” you are trying to create, you end up with a cop-thriller like “Darkness Falls”: a bizarre series of cliché after cliché, with no real work done to fill in the blanks with complexity, nuance, or even basic human reality.

The opening scene of “Darkness Falls,” directed by Julien Seri, with screenplay by Giles Daoust, shows a woman being slowly killed by two men who have invaded her home. With an unmoving camera, the woman is shown pinned against a wall by the two intruders and, as one holds a gun to her head, the other slowly shoves a lethal amount of sleeping pills down her throat. I didn’t clock how long this scene goes on, but it’s a brutal watch, particularly with the un-moving camera. The decision to film it that way was probably meant to be an “unblinking” look at violence against women, but the sheer length of the shot—not to mention the fact that the film hadn’t done any work to establish her as a human being before we are forced to watch her expire—was itself “violence” against women, primarily the woman writing this review.

Turns out this woman is the wife of Jeff, a homicide detective (a bafflingly miscast Shawn Ashmore), who finds her in the bathtub, an overdose with slit wrists. Her death is ruled a suicide, but he is convinced it was homicide. His memories of her involve golden sunset light, and the two of them staring lovingly at one another, smiling. This is what I mean by a lazy cliche, a shorthand to another shorthand. The reality of the relationship is not established. All this couple seemed to do was lie in bed, smiling at each other. At any rate, none of that matters. He is so grief-struck that not only does he go off the rails trying to solve her homicide (which no one believes is a homicide), he also makes the radical choice to grow a beard. When a clean-shaven man randomly grows a beard, you know he’s hurting.

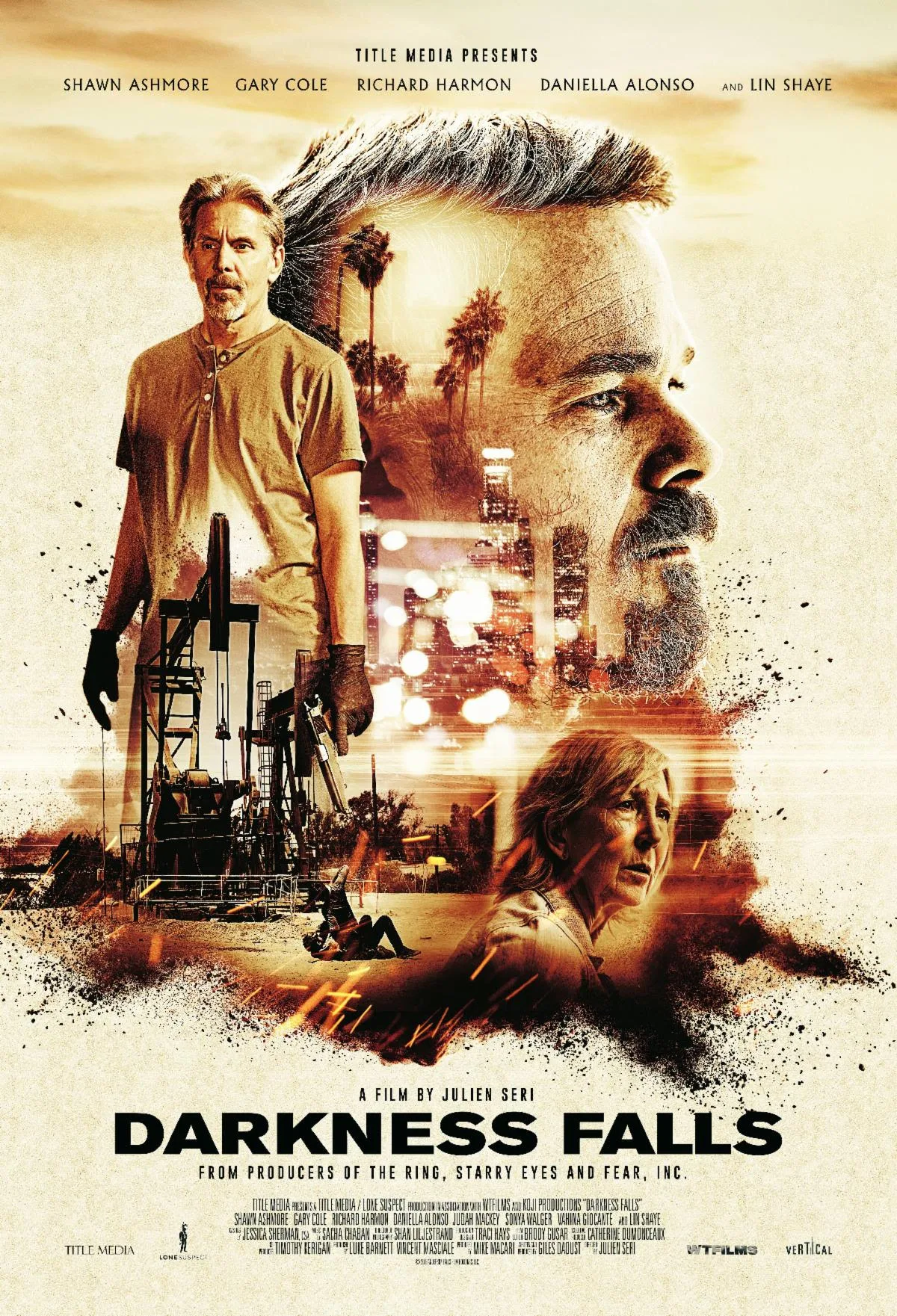

We know who did it early on, so there’s no real spoiler here to say that a misogynistic father-son duo (Gary Cole and Richard Harmon) are killing prominent women and making it look like suicide. The detective figures this out by creating a huge collage on the walls of his apartment made up of photographs of all the women who committed suicide in the area in the same manner his wife did. He goes into a psychotic fugue-state, staring at the wall. He screams at one of the photos, “I HATE YOU I HATE YOU.” I had no idea what was happening at this point, and realized only later that he was trying to “become” the killer in order to catch the killer. There are so many fine movies and television shows where a detective “becomes” the killer in order to understand the killer’s motives, but a bearded guy screaming “I HATE YOU” at some poor dead lady’s photo after what seems like a five-minute period is not the way to go about it.

Nobody can rise above the material, not even Cole, although he does his best. Harmon fares a little bit better, but he has less to do. The detective’s mother (Lin Shaye) thinks her son has gone off the deep end, and threatens to take full custody of Jeff’s son, until she does a random 180, conferring her blessings on him with a “Go forth and follow your gut instincts, my son” speech. No real work was done to show her experience, to understand what she was going through. There’s a truly weird moment when the film suddenly turns black-and-white, and instead of seeing one Shawn Ashmore, you see five of him, against a black background, each one making different wild faces at something off-camera. I guess this is to show he’s cracking up, but this surreal “flourish” was inadvertently comical. It makes him look a little bit like the opening number of “Gold Diggers of 1933” when all the dancers stand behind Ginger Rogers and swoop their arms out, turning her into an octopus-like creature.

The evil duo’s target is successful women, women who have risen above sexism and made it to the highest echelons of their chosen careers. I realize I’m being hard on “Darkness Falls,” but the attempt to create a “serious” anti-misogyny message through this shallow, improbable material—directed and written by two men, with no complex female characters onscreen—is maybe the worst part of it.