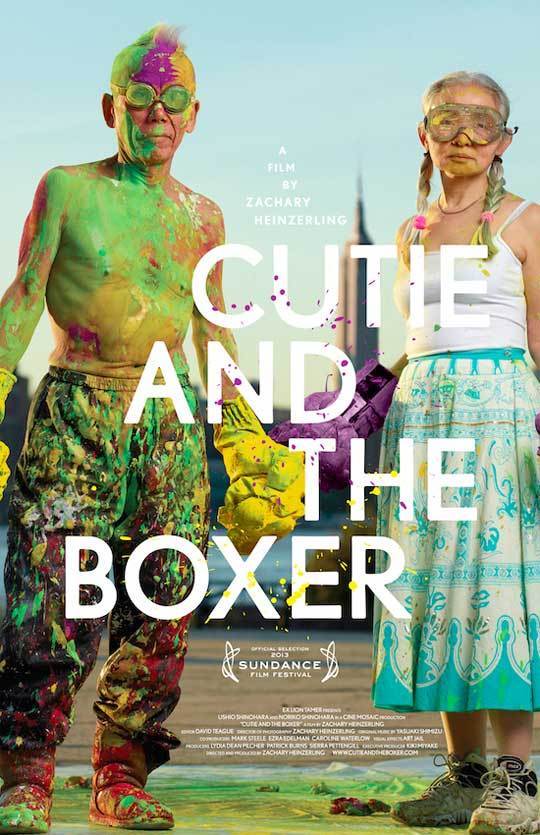

“Cutie and the Boxer,” like all truly noteworthy films, takes you by surprise with its unexpected twists and revelations. It’s a documentary about painting, but evocative music moves it along. It’s a film about a long-lasting marriage, yet also a love story filled with love-hate and resentment. Most of all, it’s about creativity, and not just the standard “artists struggling” theme, though that’s surely there. Art is a demon which can take over your life, says one of the film’s subjects, artist Ushio Shinohara.

What really makes the film come together is the paradox of this couple’s life as explained by the sometimes adorable and charming, yet frequently p.o.’ed Noriko, Shinohara’s wife. Renowned “pugilist artist” Shinohara is the avant-garde icon known mainly for his “action paintings”—bashing at huge canvases with paint-coated boxing gloves. That he’s still struggling at 80 in their loft in the Dumbo section of Brooklyn, tells part of the poignant story. Survival is a constant theme. Yet so is his concern with keeping his legacy alive, and the not-so-hidden fear that his best work may be behind him.

Four decades ago Noriko came to New York City from Japan to study art, met the famous Ushio 21 years her senior, and fell in love. She put her own artistic dreams on hold to work as a combination artist’s assistant, cook and mother to their son. All the joy went out of her art, she tells us through interviews and voice-overs, as she was constantly worried about money. Ushio counters without a tad of irony that the smaller talent should be in service to the larger.

But now comes a series of her drawings, “Cutie and Bullie,” inspired by their life, and we watch its development. (We learn that a passerby once called Noriko “cutie” and the name stuck. So did her twin pony tails, now white.) With age comes wisdom, or at least some perspective. “I think opposites attract. The ones that think alike drift apart,” she says of marriage. Their life as two artists is like “two plants in one pot, without enough nutrients. But now I think all that struggle was necessary for my art.”

“Cutie and the Boxer” is not a new-fangled doc, where you’re aware of the filmmaker. Still, after awhile you realize the couple is so comfortable in the fimmaker’s presence that they are able to freely conduct their daily lives, even act out—sometimes lash out—at each other. Zachary Heinzerling is the director-photographer, and this is his first film, winning him a “Best Director” award at the Sundance Film Festival. He has deftly woven in photos, footage from the Shinoharas’s personal films, even bits from a promotional movie about Ushio’s early years as an artist.

Exciting archival footage of the 1960s and ’70s Soho art world shows Ushio blasting upon the scene from his native Japan, hanging with Andy Warhol and friends. The downside is to see the home movies of the boozed-up artist and his friends and the parties after which Noriko had to clean up.

And in a very verité way, the movie begins with one of the home-prepared meals which dot the film, a kind of Rorschach test. Noriko seethes at how hard she has worked to make an attractive meal for them, only to see Ushio unappreciatively scarf it down. She worries they won’t have enough food, and money for it. A wildly funny sequence shows Ushio cooking for once, using celery as a kind of hamburger helper, wearing his artist’s protective glasses at the stove, and bitching that cooking is very hard.

Even if you don’t give a fig for art, their utter honesty with each other is startling. Watch Ushio’s double-take when he first sees her new work; he admits he’s jealous. It’s refreshing to hear Noriko say when he’s away, the air clears and it gets very quiet. When she gives the familiar Virginia Woolf quote about a woman needing a little money and her own room to create, somehow it doesn’t sound over-used. Maybe it’s her Japanese accent.

The doc has a built-in arc to illustrate her point: Ushio goes to Japan to sell some of his sculptures at mark-down prices. They are that far behind on the rent. Watching him trying to stuff his going-every-which-way pieces into suitcases is mildly absurdist. Yet despite Noriko’s anger with him—and he is pretty obnoxious in a lot of ways—we still see her excitedly rushing down the stairs to greet him when he returns.

Their loft is a small disaster, with the accumulation of years of living and working at home. Nevertheless it’s thrilling to watch the two of them work in their very different ways. In an instant Ushio can create a painting, splashing his colors onto a huge canvas, with the energy of a boxer. In a quieter, but just as creative, way Noriko works on her autobiographical drawings. They even move, at moments miraculously, as the film uses animation to bring them to life. You can’t help but think of the hugely epic and supremely self-confident Diego Rivera, and his wife Frida Kahlo who created her initially less acclaimed art with her personal artifacts.

The best image of the movie, though, is the conclusion of the “Cutie and the Bullie” series, shown in a dual husband-and-wife show. The black ink and pen drawings are now on a gallery wall, with red love hearts fancily floating about. Noriko has learned to “tame the bull.”