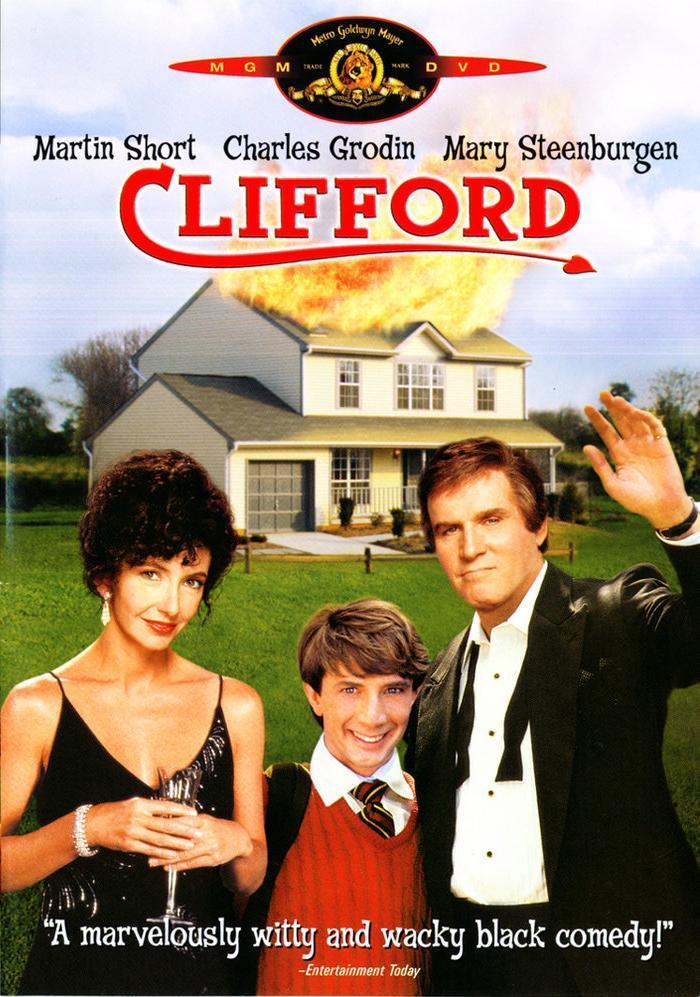

I felt a little glow as the opening titles rolled up for “Clifford”: Martin Short…Charles Grodin…Mary Steenburgen…Dabney Coleman. Funny people. Even the technical credits were promising. John A. Alonzo, great cameraman; Pembroke Herring, skilled editor. I settled in for some laughs. And waited. And waited. In a screening of some 150 people, two people laughed, once apiece. The other some 148 did not laugh at all. One of the laughers was me; I liked a moment in a showdown scene between Short and Grodin. The other person laughed right after I did, maybe because he agreed, or maybe because my laugh is darn infectious.

A movie like this is a deep mystery. It asks the question: What went wrong? “Clifford” is not bad on the acting, directing or even writing levels. It fails on a deeper level still, the level of the underlying conception. Something about the material itself is profoundly not funny. Irredeemably not funny, so that it doesn’t matter what the actors do, because they are in a movie that should never have been made.

The story opens in the year 2050, when a kindly old priest is trying to reason with a rebellious kid in a home for troubled kids. The priest (Short) tells the kid that he was once a troubled kid, himself. That sets up three flashbacks that make up most of the movie. To deal with the 2050 scenes right up front: They are completely unnecessary. Their only apparent function is to show Martin Short made up as an old man.

Now. Back to the main story, which takes place in the present. Martin Short stars as little Clifford, a brat, about 10 years old, I guess. Short plays him with no makeup other than a wig and little boy’s suits, and the camera angles are selected to make him look a foot shorter than the other actors. Clifford is a little boy from hell, a sneaky practical joker, spoiled, obnoxious. We meet him with his parents on a flight to Hawaii. He wants the plane to land in Los Angeles so he can visit the Dinosaur Park amusement park.

So he talks his way into the cockpit and shuts off the plane’s engines.

This sets up the body of the movie, in which Clifford’s uncle Martin (Charles Grodin) agrees to take the lad for a week, partly to convince his girlfriend (Mary Steenburgen) that he does, indeed, like children. But no one could like this child, who grows enraged when his uncle won’t take him to Dinosaur Park, and plays a series of practical jokes, beginning with filling his uncle’s drink with Tabasco sauce, and ending with the destruction of his uncle’s plans for the Los Angeles transportation system.

Many of the jokes are of a cruel physical nature, involving a hairpiece worn by the uncle’s boss (Dabney Coleman), or face-lifts, or phony bomb threats. What they boil down to is, little Clifford is mean, vindictive, spiteful and cruel. So hateful that if a real little boy had played him, the movie would be like “The Omen” filtered through “The Good Son” and a particularly bad evening of “Saturday Night Live.” But Martin Short is clearly not a little boy. He is a curious adult pretending to be a little boy, with odd verbal mannerisms, like always addressing his uncle with lines like “Oh, yes, My Uncle!,” and fawning up to strangers like a horny spaniel. If Clifford is not a real little boy, then what is he? The movie doesn’t know and neither does the audience, and for much of the running time we sit there staring stupefied at the screen, trying to figure out what the hell we’re supposed to be thinking.

Grodin emerges relatively unscathed, because as a smooth underactor he is able to distance himself from the melee. Steenburgen is given a scene where Coleman assaults her in the back of a limousine, for no reason that the movie really explains. Short has a couple of dance routines that have more to do with his “SNL” history than with this movie.

And then there is the “climax,” in which Uncle Martin finally does take little Clifford to the Dinosaur Park. The movie treats the sequence as a bravura set piece, but actually it’s an embarrassing assembly of shabby special effects, resulting in absolutely no comic output. At one point the movie sets up an out-of-control thrill ride, and we in the audience think we know how the laughs will build, but we’re wrong. They don’t.

To return to the underlying causes for the movie’s failure: What we have here is a suitable case for deep cinematic analysis. I’d love to hear a symposium of veteran producers, marketing guys and exhibitors discuss this film. It’s not bad in any usual way. It’s bad in a new way all its own. There is something extraterrestrial about it, as if it’s based on the sense of humor of an alien race with a completely different relationship to the physical universe. The movie is so odd, it’s almost worth seeing just because we’ll never see anything like it again. I hope.