It turns out, you can’t just wave a wand and tell a bunch of communists that it is time for capitalism. But that’s pretty much what they tried when the Soviet Union fell in 1991. First of all, capitalism is really confusing. As someone says in Alex Gibney’s new documentary “Citizen K,” “A free economy sounds nice but you have to make decisions every five minutes.” Capitalism requires more than just getting rid of the rules that prohibit private enterprise. It requires an extensive infrastructure including highly credible press, an effective regulatory and judicial system, and investors who are all sophisticated about investment and finance. What the post-Soviet Russia had was a bunch of vouchers handed out to a population who had no idea of how to determine their value and a very pressing need for money to buy food. A small group of audacious, very committed entrepreneurs bought up scads of those vouchers for kopeks on the ruble.

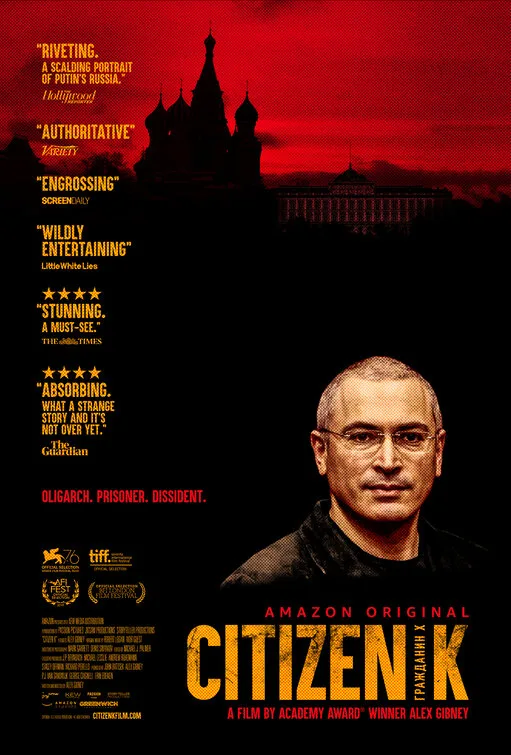

A hundred years ago, in the US, we called mega-wealthy business people like that robber barons. Today we call them oligarchs. And no one oligarched more audaciously and successfully than Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Until his favored Russian President Boris Yeltsin was gone and his replacement, an equally audacious and ambitious man named Vladimir Putin, took office. Putin considered Khodorkovsky a threat. He wanted a return to control of major business by the state—or by his own hand-picked cronies. And so, he had Khodorkovsky sent to a Siberian prison, where he stayed for ten years, until pressure from world leaders forced Putin to let him go. Now he lives in London, where his shrunken but still substantial fortune is being used to support a long-term plan to get rid of Putin and the corruption and despotism he has imposed on Russia.

“Citizen K” is skillfully made, with a compelling story, or really stories. First is Khordorkovsky who begins as a young man unapologetically admitting to being greedy and opportunistic. What he first fell in love with about the oil business, he says, is its vast scope. The movie opens with a beautiful image of the plants at the shore, then shifts to the oil processing plant, with the huge flame on top of the towering flare stack. A few years later, he has to cut salaries by 30 percent and lay off workers to stay in business. For the first time he feels some empathy for his employees. But it is only after he goes for prison that he begins to think about not just what he can do or what he wants to have but what he should do. He is truly a prisoner of conscience because he tells us he never considered compromising to become a Putin ally. “I don’t value my life that much to exchange it for losing respect,” he says. He has a lot of time to think and observe, concluding that watching the criminals in prison helps him to understand the “gangster” culture of Putin and his cronies. “Everything is built on force.”

Gibney has some remarkable footage to bring that point home. One especially chilling scene involves a furious mother of one of the crew members killed in the Kursk nuclear submarine disaster. When she challenges Putin at a public event, she is not just whisked away by security but forcibly sedated. In another, two Russian military agents blandly insist that their very brief visit to Salisbury had nothing to do with the murder of Sergei and Yulia Skripal; they say they were just there to see the city’s famous cathedral. A second storyline follows Putin from an ambitious young politician who paid to have a documentary made about him (called simply “Power“) to a ruthless leader so tyrannical he is even suspected of selecting his own “rivals” to run non-threatening campaigns against him. In a stunning example of fake news, we see how, when Khodorkovsky’s preferred candidate Yeltsin was so ill he retreated to the country dacha, TV network cop-founder Igor Malashenko re-created Yeltsin’s Moscow office in the dacha to shoot footage making voters think he was healthy enough to be re-elected.

Gibney also shows us the importance of independent media, and how transformational it can be. It is a lot of fun to see what happens when a country with no experience of political satire is presented with a puppet show featuring sharply critical take-downs of office-holders. One canny match cut takes us from a puppet figure of Putin walking away from the camera to seamlessly blend into the man himself. His choice of Russian music also complements and illuminates as well, especially the mad, lopsided “Waltz No. 2” by Dmitri Shostakovich, (best remembered from “Eyes Wide Shut“). These techniques make a vast and varied amount of arcane and dense information more accessible.

But the most striking message of the film is what it does not say, hardly even implies. At first, we watch what unfolds as an interesting story about politics and money that is far away. Then, as Putin’s role becomes clearer, we consider how it might affect the US. And then, as we see how the foundations of capitalism are vulnerable to corruption and tyranny, if independent media, political satire, and the integrity of our elections are not protected, we see how easily it might be the US.