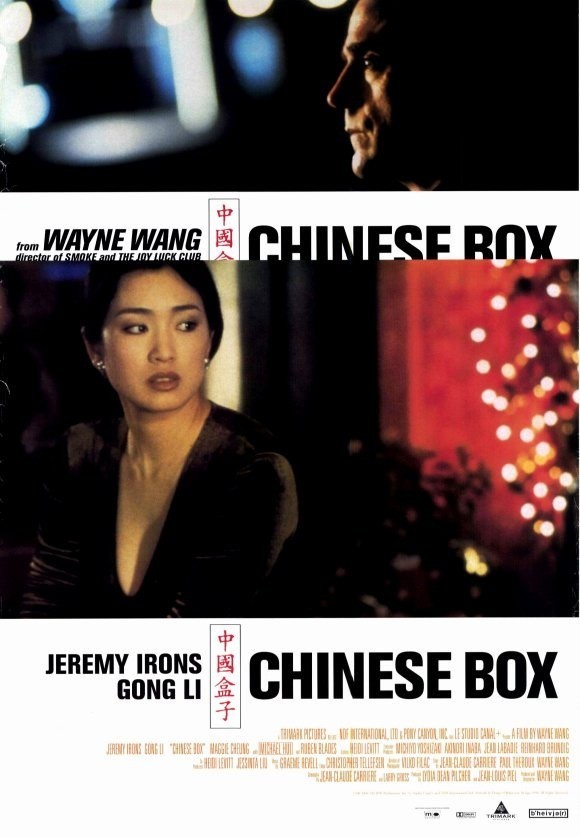

I have always been drawn toward stories of exile and expatriation, of people living as strangers in strange lands. I enjoy their bittersweet longing for other places and other friends. Jeremy Irons plays John, a character with some of those feelings, in “Chinese Box,” Wayne Wang‘s film about the last days of British colonialism in Hong Kong.

John is not a sentimentalist about the purpose of Britain’s long dominion in its last Asian colony; his latest book is titled How to Make Money in Asia. But he has grown accustomed to Hong Kong, to his crowded little room, to his regular haunts, to his guitar-playing friend Jim (Ruben Blades), and especially to Vivian (Gong Li), the bar girl he is in love with. He doesn’t want to give it up and go “home” to England–especially not after he learns he has leukemia and can expect to live about six months.

“I wonder if I can hold out longer than the British,” he muses. John looks, as Jeremy Irons often does, underfed and vaguely ill. He has the sad dignity of the intelligent loser. He met Vivian in Beijing, where she was a prostitute; they might have married then, but “it slipped away,” and now she owns a popular club, and is “engaged” to the man who bought it for her, Chang (Michael Hui). “You can spend your whole life waiting for Chang to marry you,” John warns, correctly guessing that Chang’s reputation will not withstand marriage to a hooker. But Chang leads her on, even posing for a fake “wedding photo,” and besides–Chang is the future, and poor hangdog John is the imperialist past.

The movie unfolds episodically. The screenplay by Larry Gross and Jean-Claude Carriere is based on a story by Carriere, Wang and Paul Theroux–whose latest novel, Kowloon Tong, tells of another hapless Briton stranded by the change of guard. John wanders the streets, courts Vivian, hangs out with Jim, attends a final New Year’s Eve party, takes video pictures and (after his diagnosis) begins to look around even more intensely, as if aware time is running out on his eyes and ears.

He sees a curious street sprite, a woman who conceals her face with a scarf and runs scams. She sells everything from pirated videos to cans of pre-changeover Hong Kong air. Her name is Jean, and she is played by the Hong Kong action star Maggie Cheung with a defiant, improvisational air: She may be homeless and broke, but Hong Kong is a place of opportunity, and if she is clever enough she will succeed. Jean is the most interesting character in the film because she is unpredictable; John and Vivian seem locked into their destinies.

Jean’s scarf conceals a badly scarred face, and eventually John gets her to tell her story to his video camera, by paying her. We begin to see a pattern emerging. Just as Vivian sees John as the past, the film sees Vivian as the past, and Jean as the future: In the emerging Hong Kong, glamorous bar girls and their rich tourist clients will be replaced by a tougher generation, wounded but resilient. (Jean’s scars came after a teenage suicide attempt inspired by–yes, her British boyfriend.) One character in the movie describes the departure of the British as “like a change of management in a department store.” But Wayne Wang, born in Hong Kong, now an American director (“The Joy Luck Club,” “Smoke”), expressed more ambiguity in introducing the film at the Toronto Film Festival: “I didn’t realize how much the English had always been a part of my life; I was surprised, when the flag came down, by my sense of loss.” Perhaps Vivian will feel the same way when John dies. And Jean? Will she miss him? Perhaps, but for her tomorrow is always another day.