There were some diehard Western communists who never did get the news that Josef Stalin was a murdering tyrant and his Soviet Union was not the progressive mecca of their dreams, but a sinkhole of repression, tyranny and racism. They dreamed on, long after the Hitler-Stalin pact and the show trials and all the other signals that their god had failed. Like true believers in all times and places, they made the fatal error of believing that the ends justified the means. Their error was that Stalin was not even in agreement with them about what the ends were.

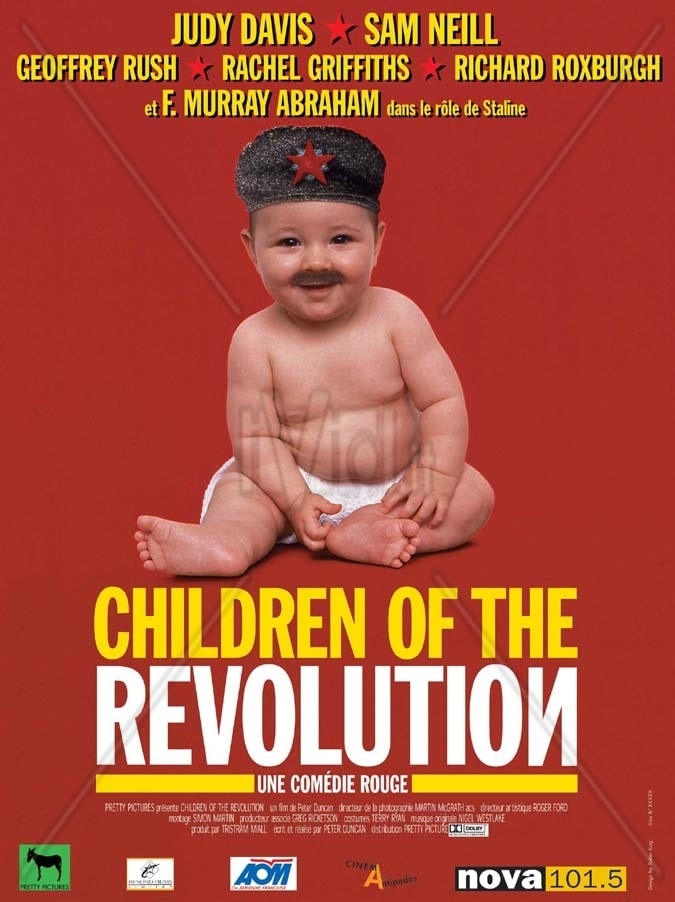

“Children of the Revolution” is a satirical comedy about one such true believer in Australia in the late 1940s. Her name is Joan (Judy Davis), she worships Stalin, and she sends him a chatty letter every week. This sets into motion a chain of events that, some 20 years later, brings Australia to within a week of civil war. “The government blamed one man,” we’re told by the movie’s newsreel narration. “He blamed his mother.” Joan’s letters find a wide readership. They are read by Australian intelligence agents, Soviet bureaucrats, and finally by Stalin (F. Murray Abraham) himself, who finds them so seductive he invites Joan to the 1952 Party Congress, and ends up sleeping with her on the last night of his life (the look on her face is priceless when Stalin sneaks an arm around her during a movie screening). Another visitor to her bed during that busy night is a double agent named Nine (Sam Neill). Nine months later, a boy named Joe is born. But is Stalin his father, as Joan insists? Whoever his biological father is, the man who raises him is Welch (Geoffrey Rush of “Shine“), a fellow traveler who stands by the fanatic Joan in good times and bad. Joan is played as only Davis could play her, with ferocious intensity and the kind of humorlessness and lack of irony that is needed to believe many forms of fundamentalism.

The fruit of the liaison between Joan and Stalin doesn’t fall far from the tree, and her son Joe (Richard Roxburgh) grows up to be an agitator who, with more modern causes and methods, is able to bring the government to its fictional crisis.

The film tells this story in many styles. There are newsreels, photo montages, clips from history, and even a musical comedy sequence in which Stalin and his three side men (Khrushchev, Beria and Malenkov) do a song-and-dance number to “I Get a Kick Out of You.” It also finds more than one acting approach, ranging from Abraham’s barely controlled farce as Stalin to Davis’ zealotry to Rush’s genial patience.

“Children of the Revolution” is the first film by writer-director Peter Duncan (whose own father was reportedly a lifelong Stalin supporter). It is enormously ambitious–maybe too much so, since it ranges so widely between styles and strategies that it distracts from its own flow. It is specifically Australian in a lot of its material (the Communist Party there was more mainstream and labor-oriented and thus respectable than it ever was in the United States), and American audiences, I think, will tend to view it more from the outside, as a curiosity, rather than as a film that speaks to them directly.