“We believe that politics is the way you live your life, not who you support. It’s not in terms of rallies or speeches or political programs. It is in terms of images and in terms of transforming people’s lives.”

That was Abbie Hoffman, the notorious Yippie, expressing his dedication to politics as “total theater” in 1968. He was just over 30 then, and never to be trusted, which is exactly what so many people found galvanizing about this gregarious, frizzy-haired prankster.

In the great 1960s clash of generational values, Hoffman believed that his side would prevail because it had better symbols. As he framed it, the comedic/dramatic faceoff was between peace, love and freedom on one hand, and war, repression and oppression on the other. When you look at it in those terms, it’s hard to argue with him.

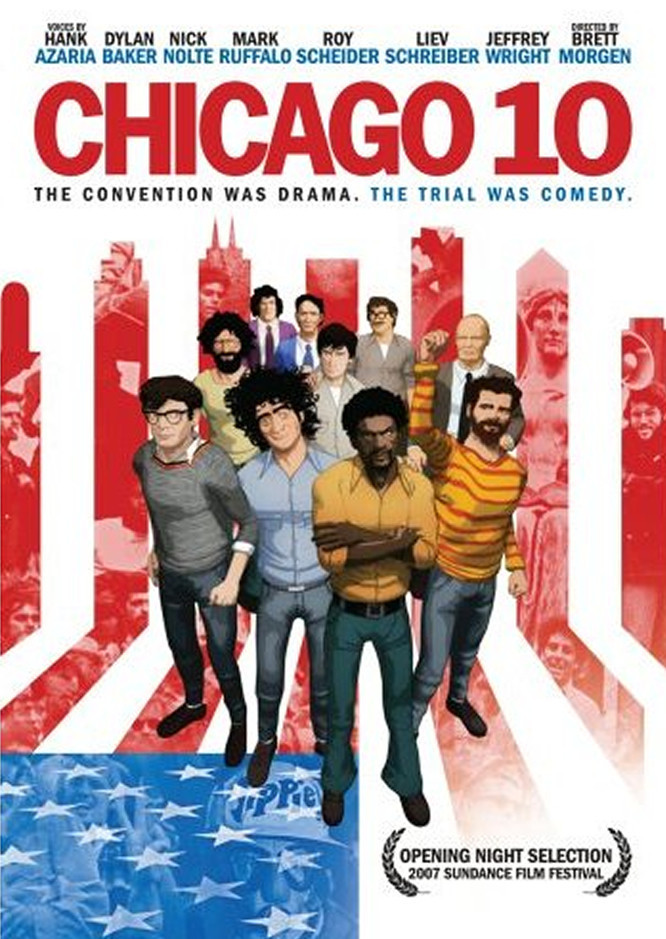

Through the kaleidoscopic prism of Brett Morgen’s uproarious “Chicago 10,” a zippy mixture of documentary footage and motion-capture animation, we see how the confrontations between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention played out as political theater. What began as slapstick comedy in Grant Park quickly turned into heavy drama when billy clubs and tear gas canisters started flying. All the while, the demonstrators chanted: “The whole world’s watching!”

The whole world was. Hoffman and cohorts were charged with conspiracy and incitement for their roles in the convention protests. They became renowned as the Chicago Seven — later the Chicago Eight, when Black Panther leader Bobby Seale was added to the list of accused, then back to the Chicago Seven again when Seale’s case was tried separately. (The 10 of the film’s title includes the defense attorneys, who were charged with contempt of court.) During the trial, the defendants turned Judge Julius Hoffman’s kangaroo courtroom into the stage for a wild farce, complete with kisses, costumes and paper airplanes. Guest-star witnesses included Norman Mailer and Allen Ginsburg.

“Our role in the court was to destroy [the judge’s] authority,” Hoffman explained (he preferred to be called “Abbie”). Now that’s theater. And cinema. When the scruffy band of radical improvisers are met with barrages of flashbulbs, they are amused and aghast at their own celebrity: “It’s ‘La Dolce Vita’!”

At some point in the preparations for the protests, the organizers (if that’s not too strong a word) said they realized that they wouldn’t have to do a thing to make their points — that the mere presence of so many anti-establishment civil-disobedients in Chicago would prompt a reaction from the authorities (quite possibly a violent one) that would reveal the truth to the world. When CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, known as “the most respected man in America,” announced on television that the Democratic National Convention was convening in what was, in effect, “a police state,” well, that’s the way it was.

All these incidents are packed into Morgen’s film, which bursts with Yippie-ish irreverence and political fervor. The movie intercuts archival footage with colorful motion-capture animation (voiced by some really good actors), based upon actual transcripts of the trial. These play, quite intentionally, like countercultural Looney Tunes, with Hoffman the Younger as the Tasmanian Devil and Hoffman the Elder as Elmer Fudd. Whether appearing as himself in film clips, or in Hank Azaria’s animated incarnation, Abbie is definitely the star of the picture.

The irreverent attitude of “Chicago 10” is in synch with the times it portrays. Giddy, funny and sometimes nightmarishly absurd, it’s an apple-cart-upsetting performance piece shot through with blasting music from Eminem, the Beastie Boys and Rage Against the Machine. As an activist documentary with a contemporary agenda, it doesn’t pretend to be “objective” (whatever that means), but to find inspiration in the passion and irreverence of its heroes.

Through the prism of this movie we can see how Hoffman’s satirical brand of “political theater,” a concept he did not invent but adeptly exploited, may have seemed both cynical and naive at the time, but was keenly perceptive, even prescient. In the decades since, the political manipulation of symbols and images — the spectacle of the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers, or the awkwardly staged toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad, for example — illustrate precisely what he was talking about, though on a scale and level of deadly sophistication he may never have imagined.

In a key but fleeting image, a documentary camera catches an old man on his way to the convention. He wears a light suit and a quaint straw Humphrey hat, already a walking symbol of the outmoded party politics that the 1968 demonstrations rendered instantly irrelevant. The passing of his moment is indelibly captured in a few seconds of film, a testimonial to what a long, strange trip it’s been.

Jim Emerson is the editor of rogerebert.com.