No doubt most people have read the occasional news story about the world’s coral reefs disappearing at an alarming rate, but so far this has been the very definition of an “out of sight, out of mind” problem. By all indications, Jeff Orlowski’s “Chasing Coral” could be a game changer in terms of public perception. Like Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” and Louis Psihoyos’ “The Cove” in years past, the film makes a powerful case less through argument than by using cinema’s most basic tool: visual proof.

Like all such documentaries, this one may focus on the physical world, but it also has human protagonists. In fact, there are several interesting characters—as well as a large supporting cast, mainly scientists—in the film. But in a structural sense, “Chasing Coral” is somewhat unusual in having one main character who dominates the story early on, and another who comes to the fore in the second half.

The first of these, Richard Vevers, was a London advertising executive who, after climbing the corporate ladder, decided he’d had enough of selling toilet paper and set off for the South Seas. Landing eventually in Australia, he began a new career in undersea photography and, after a few years, noticed that some of his favorite marine creatures were disappearing.

Once he decided to focus on the plight of corals, Vevers’ instincts as an advertising man came into play. Wanting to show others what was happening, he set out document the undersea world much as Google Earth had mapped the surface. And not long after that, by chance he saw a documentary called “Chasing Ice” by Jeff Orlowski and realized that it did for the world’s vanishing glaciers what he thought needed to be done for coral reefs. So Orlowski was sought out and engaged as the director of “Chasing Coral.”

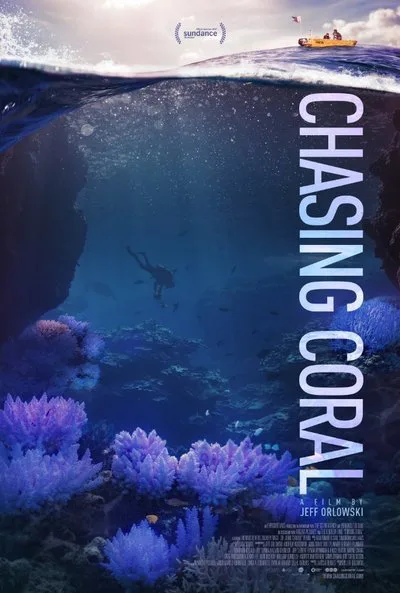

It must be noted that, from its first moments on, “Chasing Coral” is simply staggering visually. Older viewers are bound to marvel at what a distance we’ve come in terms of undersea cinematography since the prime of French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, whose TV docs were popular in decades past. As important as those shows were, their 16mm images now look dim and murky compared to the luminous, crystal-clear and spectacularly colorful digital images in this film.

Early on, the viewer’s eye is enraptured by the world the camera beholds, and it’s easy to imagine how pleasurable a feature-length tour of such sights might be. But there is trouble down below, and the film heads directly for it.

Corals, it stresses, may look like giant undersea carpets or rock formations, but they are living organisms. Seen up close, they have an incredible variety and beauty. They are also vastly important to all life on earth as the environmental basis for the fish and other marine life that supports much human life. And in the last three decades they’ve been dying off at a stunning rate.

This is where the imagery in “Chasing Coral” goes from intoxicating to chilling. The phenomenon called bleaching is when corals give up their vibrant colors and become a ghostly white, usually dying thereafter. When Orlowski and his crew sail over living coral and then the images change to the mortuaries of bleached coral, it’s like aerial views of Dublin or Salzburg morphing into pictures of bombed-out Dresden or Mosul.

There seems no doubt that the corals’ death spiral is the result of global climate change. The film makes the point that 93% of the rise in temperatures is absorbed by the oceans, so that while climate change deniers debate changes on the earth’s surface and atmosphere, the seas are where the most massive and incontrovertible damage is being done. And no one knows what the ultimate effect of this will be. The predictions range from mildly catastrophic to entirely catastrophic: a collapse of the whole global ecosystem.

This is a relatively recent and rapidly developing story. Australia’s massive Great Barrier Reef, the focus of the much of the film’s latter half, lost nearly a third of its coral in 2016. That’s one year, in an area the size of the whole eastern U.S. coastline. Part of the drama in “Chasing Coral” has to do with Orlowski and company trying to document the changes. They have special undersea time-lapse cameras developed and deployed, but it turns out that all but one take out-of-focus pictures. So it’s back to the drawing board, but with an ever-increasing sense of urgency as scientists predict a massive impending coral die-off.

In this latter section of the story, our attention shifts to Zack Rago, a recent college grad whose teacher parents instilled in him a love of the sea. A self-described “coral nerd,” Rago has winsome blond good looks and a youthful openness that conveys his passion for undersea life but also the shock at seeing much of it expiring before his eyes. He doesn’t cry when he shows some of the images he’s gathered to a conference of coral experts, but there are some moist eyes in the audience.

The film ends on an upbeat note, asserting the possibility of restoring coral life through changes in human behavior. But that must of course begin with an awareness of the problem, which is where “Chasing Coral” and similar efforts come in. The film was produced by Netflix, which deserves credit and thanks for it. Here too it may be that technology can help stimulate solutions. Indeed, thanks to the network’s reach, within a few days the film might be seen by far more people worldwide than saw “An Inconvenient Truth” on its long march from Sundance to the Oscars.