A drama teacher once told me that great drama is about the most important day in the life of the protagonist. Even if it was a generalization designed to teach a student how to bring gravity to a performance, it’s often true, but not always. Great storytellers can make great drama from seemingly average days in their character’s lives, sometimes offering even more insight into the human condition by transcending the mundane than highlighting the abnormal. There are several “average days” in Kelly Reichardt’s sublime “Certain Women,” an adaptation of three short stories by Maile Meloy. Working with the most high-profile cast she has to date, Reichardt delivers a multi-faceted character study, a sketch of intersecting lives in a small Montana town. It is purposefully slow, a film meant to be lived in and considered carefully when it’s done. Almost none of it feels as “important” as my teacher explained and yet it is still great drama.

“Certain Women” opens with a train moving slowly through the heartland of Montana, honking its horn occasionally along the way. We will hear that train again, blaring its horn in the background of these characters’ lives, both connecting them in our subconscious and serving thematic purpose. Reichardt returns to images of life going past this mountain town—trains, freeways in the distance, a flowing river—to remind us of both the ordinary nature of these stories and to connect them to each other and even our lives.

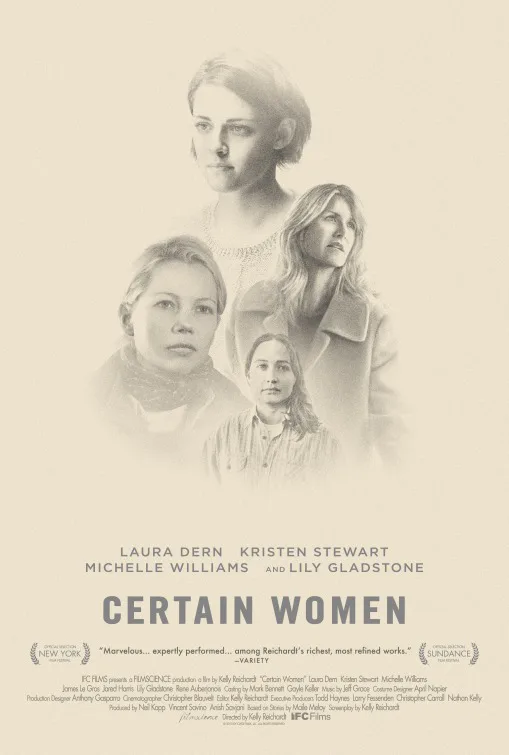

The first of three barely interlocking stories opens with a lawyer named Laura Wells (Laura Dern) on her lunchtime affair with a married man named Ryan (James Le Gros). She returns to her office to find her most annoying client, a man named Fuller (Jared Harris), who won’t take her legal advice that he doesn’t have a disability case against his former employer because he took money from them after the accident. It turned out to not be nearly enough money but it derailed any future legal action. She takes him to a male colleague in a neighboring city, who tells him the exact same thing, but he listens this time. Reichardt is subtly laying thematic foundations about the ways in which people interact with each other—female attorneys and male clients, husbands and wives, teachers and students.

After Fuller does something drastic that serves as the only real “action” of “Certain Women,” we transition to the story of Gina Lewis (Michelle Williams), wife to Ryan, the man we met earlier getting dressed with Laura. The effect of that earlier scene is subtle but crucial because we bring baggage to this second story by virtue of the fact that we know that this isn’t a healthy marriage. It looks like everything is relatively fine, but Ryan is cheating. So when we see them working on a house they’re building from the ground up, we know the foundation is a little weak.

Gina, Ryan and their daughter are camping on the site, next to a river, where their home will be built. On the way home, they stop off at the house of an elderly man named Albert (Rene Auberjonois), from whom they want to buy a pile of sandstone. Albert hesitates at first, melancholic over his original plans to use it for something that never happened. The gender dynamics here are crucial to understanding the scene as Albert will only speak to Ryan, making Gina more aggravated.

Finally, there’s the third story of “Certain Women,” which could stand alone as one of my favorite short films in years. Lily Gladstone stars as Jamie, a ranch hand living on her own on an isolated farm. Her only friends seems to be the adorable dog who runs alongside her tractor, although Jamie’s life is not presented as a miserable one. It’s just an existence in which not much changes to day to day. And then she stumbles into a class on school law being taught by a woman named Beth (Kristen Stewart). They go out to eat and strike up a friendship and Beth becomes the break from the norm that Jamie needs.

Every one of these stories has a sense of inevitability, like that river moving through the heartland. Whether it’s a disgruntled client who sees no way out of his predicament, a man who closes a chapter in his life when he parts with his sandstone, or the daily grind of working on a farm. These are normal people, like you and me, and it’s that relatability that makes Reichardt’s work here so powerful. Every single character, even the minor ones, feel like they exist before they come into frame and keep going long after. If anything, it’s the male characters who reach finality—the female ones keep moving forward to the next client, project, and day on the farm. Perhaps there’s something of a statement there. That’s for you to decide.

As for performances, this could be Reichardt’s best work to date. Again, there’s such a lived-in quality to Dern’s approach or Harris’ frustration or Gladstone’s quiet emotion. Williams, a regular Reichardt collaborator, gets the least satisfying of the three narratives, but the final 45 minutes, which also features spectacular work from Stewart, more than makes up for it. There’s so much internal monologue in Reichardt’s approach. It’s more about what Jamie doesn’t say to Beth or what Laura stops herself from saying to Fuller that makes the movie work. We see so many films in which characters are constantly expressing exactly what they think and feel in ways that no one does in the real world. It’s because most filmmakers are afraid of silence. Kelly Reichardt knows that so much can be said with silence. It can even be the subject of great drama.