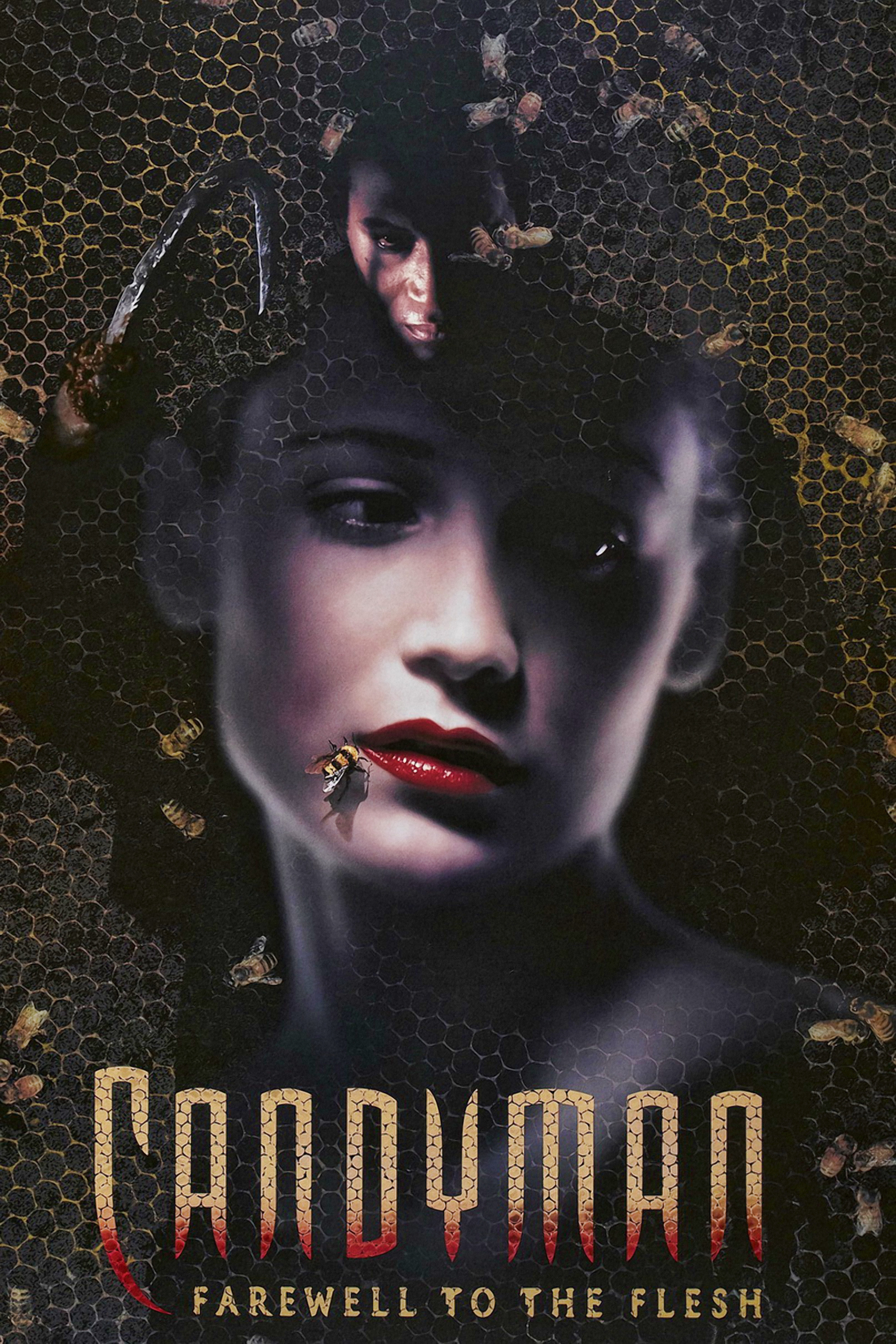

In the original “Candyman” (1992), a couple of Ph.D.s from the University of Illinois theorized that the Candyman was an urban legend, brought to life by the faith of all the people who believed in him. But it turned out there was a much more gothic and supernatural explanation, and we learn more about his origins in the new “Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh.”

The Candyman stories, based on books by Clive Barker, are an attempt to make an intelligent fable out of a bogeyman, and Bernard Rose’s 1992 film did a good job of it, with Virginia Madsen and Kasi Lemmons as the researchers who track down tales of a slasher with a hook for a hand. He was terrorizing Chicago’s Cabrini-Green public housing complex, but in the second film he has moved back home to New Orleans, and started preying on his own descendants, instead of innocent bystanders.

In the new film, directed by Bill Condon, there’s once again an attempt to establish a real world in which Candymen aren’t possible. Kelly Rowan stars as a New Orleans schoolteacher whose father was killed years earlier, Candyman-style. Now her brother has been accused of killing a Candyman expert, and a student in her class has started drawing the Candyman. How does the kid know about him?

The movie doesn’t develop, alas, with the patience and restraint of the earlier film. It’s got one of those soundtracks where everyday sounds are amplified into gut-churning shockaramas, and where we are constantly being startled by false alarms. There’s a scene, for example, where a character walks up behind the teacher, and the soundtrack explodes. My notes read: Scream! Shock! Rumble! Crack! – followed, of course, by the guy saying, “Sorry, I thought you heard me.”

The movie also pulls the old “It’s only a cat” routine, where a shrieking, snarling presence from out of frame turns out, yes, to only be a cat. There is even an “it’s only a raven” sequence, no doubt in honor of Clive Barker’s predecessor in the macabre, Edgar Allan Poe.

The story proceeds. Characters near and dear to Rowan are slashed Candyman-style. Eventually, led by the little student from her class who seems tuned in to the Candyman, she is led to an old plantation, where all is explained. Read no further if you would rather not know that the Candyman turns out to have been a slave who fell in love with his master’s daughter, and she with him. When she became pregnant, the enraged plantation owner set a mob on the slave, which cut off his arm and smeared him with honey, so that he was stung by thousands of bees, which is how he got the name Candyman.

Is there an entomologist among us? Are bees attracted by honey? I would have guessed they’d be rather blase about it, and would be more quickly attracted if the victim had been smeared with one of those perfumes they advertise on the cable TV. Never mind. The slave, whose name is Daniel Robitaille, sees his bee-stung face in his lover’s mirror, and somehow his spirit goes into the mirror, so that if you look in a mirror and say “Candyman” five times, that’s going to be more or less the last thing you do. (I have tried this, and it doesn’t work.)

The story goes to some lengths to develop sympathy for the terrible tortures he was subjected to, as a victim of racism who dared to love a white woman. (Because the Candyman is played by Tony Todd, who has more than a passing resemblance to O.J. Simpson, there are several scenes that have a curious double resonance.)

I suppose that Clive Barker would be happy to explain to us how “Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh” is a statement against racism, and maybe it is, although it sure does go the long way around. The message may be that because slaves were mistreated, we pay the price today, perhaps every time we look in the mirror and see our racism reflected back at us. (Hey, I didn’t take those EngLit symbology classes for nothing.)

Like many movies with morals at the end, however, it has its slasher and eats him, too. If the last 15 minutes of the movie are devoted to creating understanding for Daniel Robitaille, the first 85 are devoted to exploiting fears of slasher attacks by tall black men, with or without a hook for a hand. And the flashback is overly elaborate: Did the mob vote against lynching Robitaille, deciding, “Naw, let’s just cut off his hand and smear him with honey, so he can become an urban legend?” If not, it seems they went to a lot more trouble than most mobs in those sad days.

I am left with questions. Why did the Candyman visit Chicago? Why did he prey on innocent young black victims who had done him no harm? Which is he, a mythical force brought to reality by psychic mind power, or an immortal being fueled by the life force of the bees, who lives in mirrors? I spend my days pondering questions such as these, so you won’t have to.