The 21st century has not yet produced a whole lot of noteworthy “what is reality?” movies, perhaps because we’re too busy wondering “what is reality?” in real life to be potentially entertained by a fictional iteration of the question. Or maybe it’s just because David Lynch hasn’t made a feature film in over a decade.

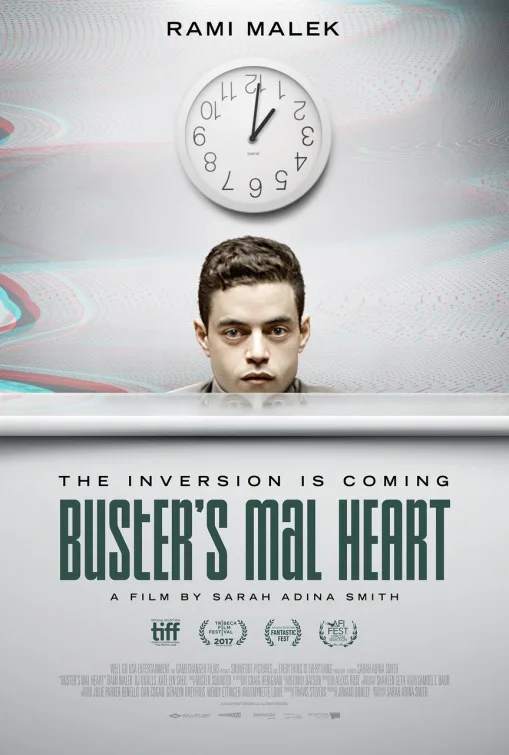

It’s a shame that this movie has a title that sounds like the filmmaker’s dare to any indie distributor’s marketing department, because “Buster’s Mal Heart” is a genuinely noteworthy picture that deserves an audience. Written and directed by Sarah Adina Smith, it’s a movie that puts the viewer into a bad dream, and is very canny in dispensing the keys to unlock the meanings of that dream—and in strategically withholding some of those keys.

The movie begins with images of a man, the actor Rami Malek (whose popular television show “Mr. Robot” might usefully acclimate some viewers to the mind-bending properties of this work) running through a darkening forest. Before we can establish why he’s fleeing, Malek is seen with a long beard and long hair, stealthily breaking into a cozy mountain home while media reports on the soundtrack tell of a “hermit” “mountain man” named Buster, a mysterious breaking-and-entering figure who, the announcers insist, is of no genuine threat to the populace at large. And then some scenes depict Malek again, once-more clean shaven, as a married father with professional and personal challenges. He works as a “concierge” at a corporatized motel, he’s obligated to take on the night shift, he’s thus separated from his wife and daughter, which is on the other hand not too terrible because they’re poor and have to live with his awful moralizing busybody mother-in-law. Sounds stressful, right? It is. The role gives Malek ample opportunity to perform the silent, wide-eyed panic at which he’s practically a virtuoso.

In small dribbles, details of this banal Midwest hand-to-mouth existence emerge. Jonah (for this is the concierge’s name) is married to Marty (Kate Lyn Sheil in a disciplined, enigmatic turn), a former drug addict who’s found God and a church. Jonah himself seems to have less certainty in his philosophy of life. This makes him unusually susceptible to the theories of Brown, who’s played by DJ Qualls with a chilled, spooky quality. Brown shows up at the hotel late one night, without ID or a credit card; he blatantly snorts cocaine in front of Jonah, who tries to throw him out but instead winds up pouring him some drinks from the long-closed bar. “The better the system, the more of a trap it is for the individual,” Brown avers to Jonah, in the process of spinning out an elaborate prediction of a cataclysmic event called “The Inversion.” This is tied into Y2K speculation (the film seems to be set in 1999), and also to theories Jonah has been getting from a weird local television program, proposing an interstellar physics that goes “from black holes to buttholes.” All this might lead one to believe that Jonah is head for a psychotic break, and that the movie’s intercutting between Jonah and “Buster” are temporal shifts between past and present, depicting one character. Only that’s not where this vision is heading.

Writer/director Smith pulls off her difficult vision with exemplary flair; this is a very accomplished second feature. It’s not without glitches—a scene in which Buster evacuates into a saucepan while a Spanish-language version of the reggae classic “Rivers of Babylon” plays on the soundtrack was a little too gross-twee for my tastes—but where it counts, as in a scene in which Buster makes dinner for an older couple that he’s taken hostage in their own home, she imbues her scenes with both conventional suspense and an underlying discomfort that feels like a bad psychic rash. “Buster’s Mal Heart” builds to a conclusion that’s both head-scratching and a little heartbreaking, two qualities that are hard enough to pull off by themselves, let alone simultaneously.