“Brothers by Blood” is a waiting game in which both the audience and the movie lose. For all of its posturing—its grimacing tough guys, their many leather coats, and the gruesome real-life mob corpses in the opening credits—the film struggles to builds a sense of danger that makes the slow burn worth it. Even the movie’s main conflict, of whether or not to kill your hot-headed gangster cousin, lands with a shrug of an ending. The lives of two cousins may be at stake in “Brothers by Blood,” but only on paper.

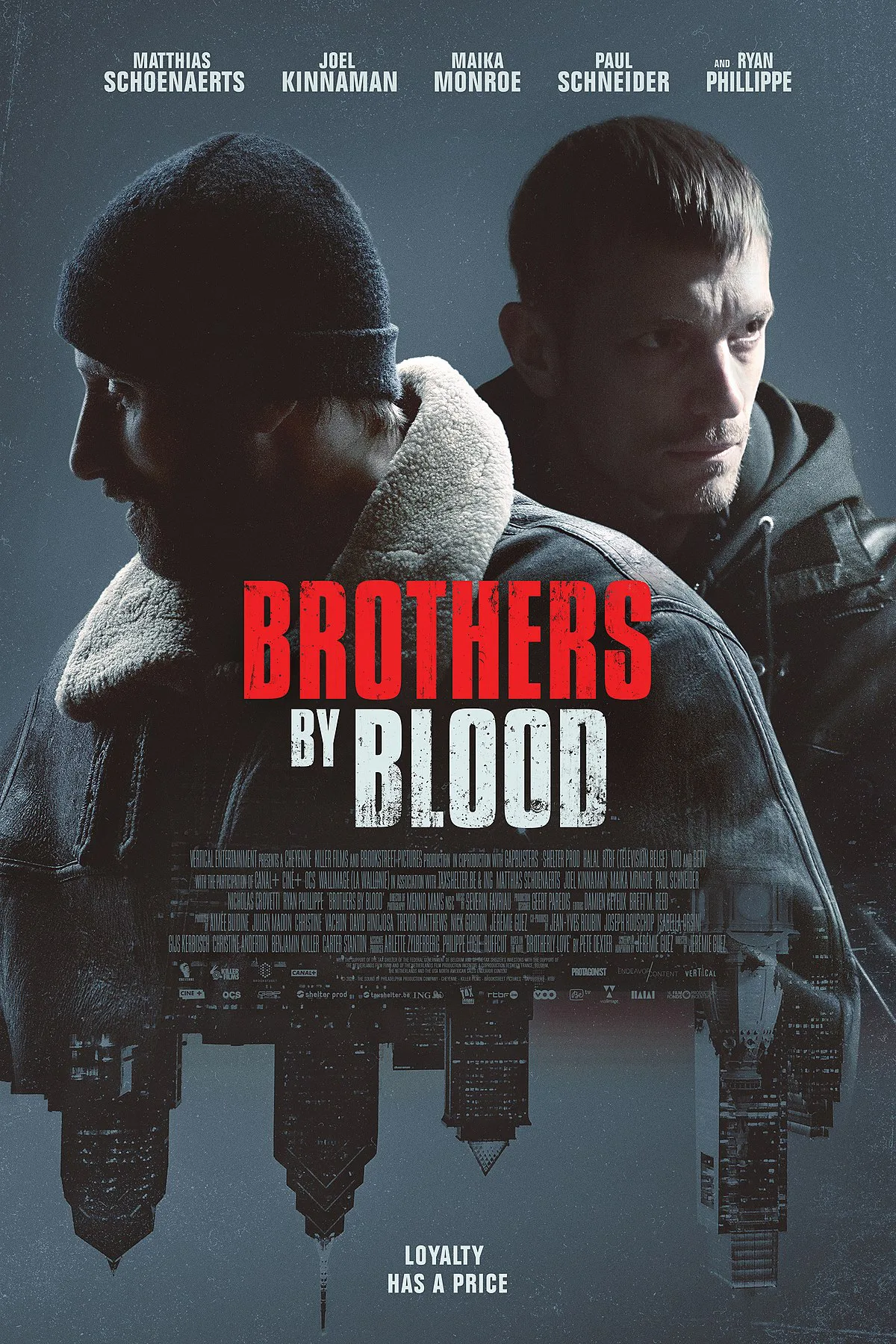

This the kind of brooding crime drama that lives or dies based on a tough guy’s silence, and here it become a dead weight. In this case, such quiet moments belong to Matthias Schoenaerts, a usually fascinating mug and bulky body in nearly anything (including “The Drop,” which this movie dearly wishes it could be). The aforementioned cousin murder quandary falls on his shoulders as he wrestles with what to do about Michael (an irascible but mumbly Joel Kinnaman), who he grew up with like a brother, and has watched slowly turn into a destructive, petulant heavy. There’s an ongoing battle between the Irish and the Italian gangs in the city, and Michael’s desire to finally end it on behalf of the Italians, with some extreme power plays, is going to do more harm than good.

Schoenaerts’ Peter spends a good deal of “Brothers by Blood” thinking about what he should do, or so we project. There’s not a lot going on in this script by writer/director Jérémie Guez (adapted from the 1991 novel Brotherly Love by Pete Dexter), which sorely feels like it’s had atmosphere and character development ripped away from it, so we have to assume that there’s a lot going on behind Schoenaerts’ weary gazes. In some shots, he appears tortured. In many others, you’re more inclined to think that he’s just chilly.

The brash masculinity of this story—which is meant to be its main selling point—turns into gibberish, especially with the muffled conversations from Kinnaman and the script’s tediously vague sense of what violent business these cousins are in. When Michael says between his constantly gritted teeth an aside about “taking over the business,” it’s confusing. (It’s not a good sign when a gangster movie has you thinking, “Take what, exactly?”) “Power” is the easy answer, “turf” a little more so, but there’s still no sense of what’s really at stake. At the beginning it’s the notion that Michael and Peter can get bribing customers decoy “jobs” as roofers, but that’s hardly an interesting scandal. The film stubbornly refuses to really elaborate on this, instead making it a story of Peter slowly accepting what he must do, all while getting whacked seems like the circle of life.

Part of this movie’s interest in toughness involves a cycle of violence, which is represented with flashbacks that involve young Peter (Nicholas Crovetti) witnessing the traumatic dissolution of his family. Each time we check back in with Peter, treading softly through his childhood home, the boy is closer to his final form as A Disturbed Man: first it’s the tragic death of his sister, then the mental illness of his mother, and later the fate of his gangster father (Ryan Phillippe), who tries to guide his son in the ways of smart strength. Phillippe is in the film for maybe ten minutes tops, and yet he gets both the best line in the movie and its solely memorable moment. When speaking to young Peter, he offers legitimately meaningful and poetic advice: “It’s one thing to put your fist though drywall. It’s something else when you hit the studs.” If the rest of the movie didn’t seem so obviously defective with the gangster movie blueprint, you might lament that it didn’t have more of that poignancy.

Midway through the generic bravado of “Brothers by Blood,” it hits the studs. Killings and beatings happen at such a clip that they don’t create any emotional momentum, especially when the film is little but Michael’s reckless behavior as wannabe leader (which Kinnaman treats with dull restraint) followed up by Peter’s delayed admonishment. All the while, its actors—a solid bunch who are often as good as their scripts—are stranded. Maika Monroe appears in a few scenes as Grace, the bartending sister to the slimy Jimmy (Paul Schneider), a restaurant owner who owes Michael money and is going to pay. But Monroe also gets little to work with, and the relief that the movie gives her a little more to do than pouring drinks is the type of kudos “Brothers by Blood” demands.

A superficial force eats at this movie from the inside, including the way that it’s a brawny script with nil visual grit, and a style that mostly announces itself with sporadic neo-noir lighting. Even Peter’s hobby of boxing is a shorthand to reference American masculinity (and recalls Schoenaerts, dukes up, in the Belgian film “Bullhead”) without having to dig into it. For eye-rolling context, Guez also introduces Michael as a Trump voter in 2016 (“He made billions, he can run this f**king country”), a detail that you can tell the filmmakers think is brilliant character development, but simply isn’t.

You don’t need to know Philadelphia to be frustrated about how much the city is a non-factor in this film. First the story was called Brotherly Love when it was a book, and before this final title the movie was known as “The Sound of Philadelphia.” But there’s no sense of specificity aside from generic B-roll shots of the city, as the movie’s main locations (of a boxing gym, a restaurant, an apartment) make this American microcosm as generic as possible. Rarely does a movie with a specific location and metaphor seem so lost. When one of this film’s tough guys brushes off violent business with a “Hey, this is Philadelphia,” they might as well be talking about Phoenix.

Now playing in select theaters and available on digital platforms.