Michael Peterson tells us he was born into a normal middle-class family. He does not blame his childhood or anything else for the way he turned out, and neither does this film. It regards him as a natural history exhibit. No more would we blame him on his childhood than we would blame a venomous snake for its behavior. It is their nature to behave as they do.

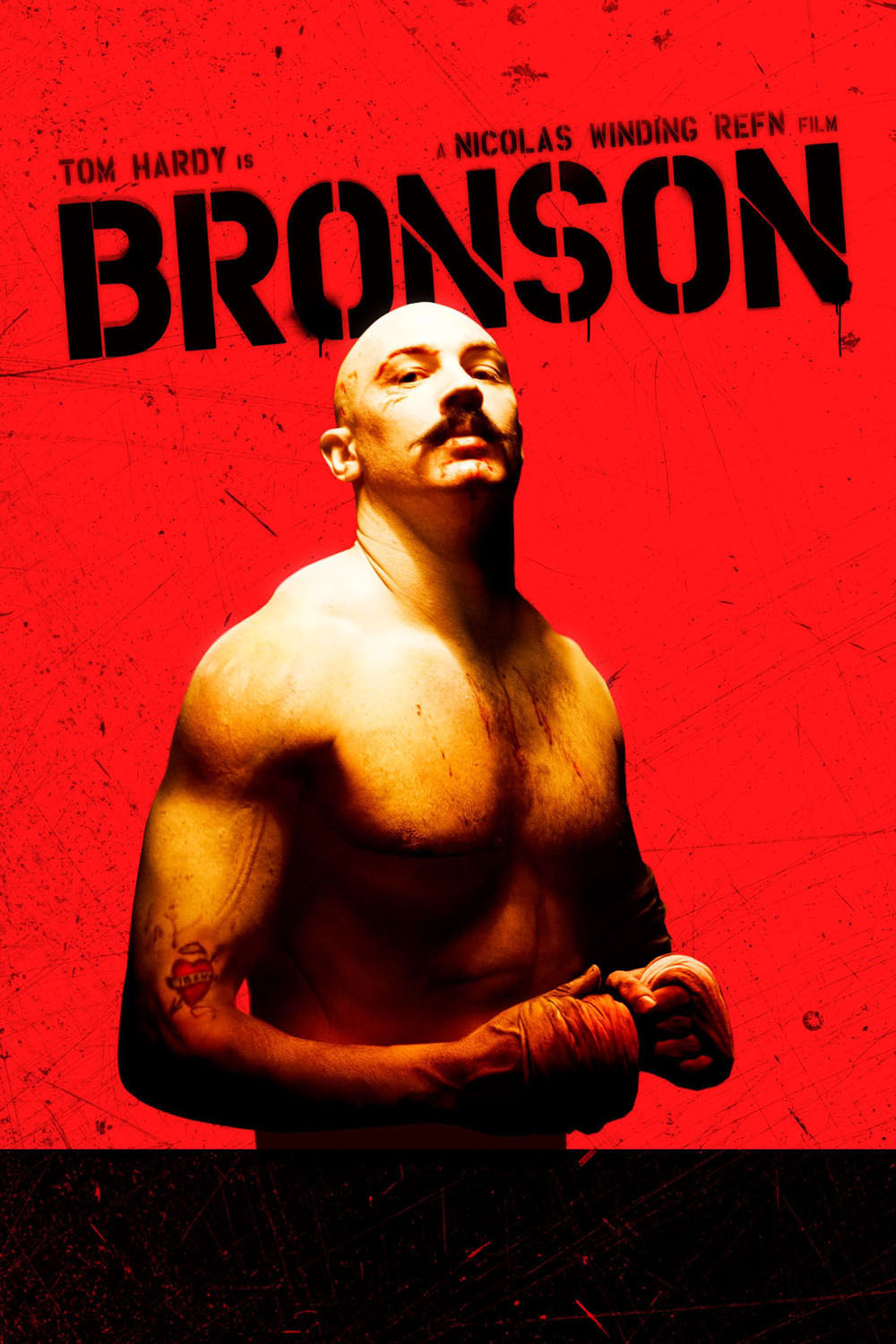

At an early age, after seeing “Death Wish,” young Michael took the name of Charles Bronson. And as Bronson, he has become the U.K.’s most famous prisoner and without any doubt, its most violent. With a shaved head and a comic-opera mustache, he likes to strip naked and grease himself before going into action.

His favorite pastime is taking a hostage and then engaging in a bloody battle with the guards who charge to the rescue, swinging clubs and beating him into submission. He has triggered this scenario many times, perhaps because he enjoys it so much. Originally sentenced to seven years (“You’ll be out in three,” his mother calls to him in the courtroom), he has now served 34 uninterrupted years, 30 of them in solitary confinement.

Why? We don’t know. The movie doesn’t know. If Bronson knows, he’s not telling. The movie takes on a fearsome purity, refusing to find reasons, indifferent to motives, not even finding causes and effects. It is 92 minutes of rage, acted by Tom Hardy. This is a versatile actor. As you’d expect, he’s made a lot of British gangster movies (“RocknRolla,” “Layer Cake,” “Sucker Punch”) but he’s also played Bill Sikes in “Oliver Twist” and Heathcliff in a TV adaptation of “Wuthering Heights.”

Hardy brings a raw physicality to the role, leaping naked about his cell, jumping from tables, hurtling himself into half a dozen guards, heedless of pain or harm. It must hurt him, because it makes us wince to watch. The word is animalistic.

They say one definition of insanity is when you repeat the same action expecting a different result. Bronson must therefore not be insane. He repeats the same actions expecting the same results. He goes out of his way to avoid different outcomes. During one stretch of comparative passivity, he’s allowed to go to the prison art room and work with an instructor. He enjoys this, I think. He isn’t a bad artist. When it appears he may be showing progress, what does he do? He takes the instructor hostage and is beaten senseless by guards.

“I showed magic in there!” he shouts after one brawl, bleeding in triumph. How’s that? Magic, like in opening night? Does he expect a standing ovation? I believe most of us, no matter how self-destructive, expect some sort of reward for our behavior. It may not be some people’s idea of a reward, but it’s ours. Is Bronson then an extreme masochist, who only wants to be hurt? They say there are masochists like that, but surely there’s a limit. What kind of passionate dementia does it require to want to be beaten bloody for 34 straight years?

I suppose, after all, Nicolas Winding Refn, the director and co-writer of “Bronson,” was wise to leave out any sort of an explanation. Can you imagine how you’d cringe if the film ended in a flashback of little Mickey undergoing childhood trauma? There is some human behavior beyond our ability to comprehend. I was reading a theory the other day that a few people just happen to be pure evil. I’m afraid I believe it. They lack any conscience, any sense of pity or empathy for their victims. But Bronson is his own victim. How do you figure that?