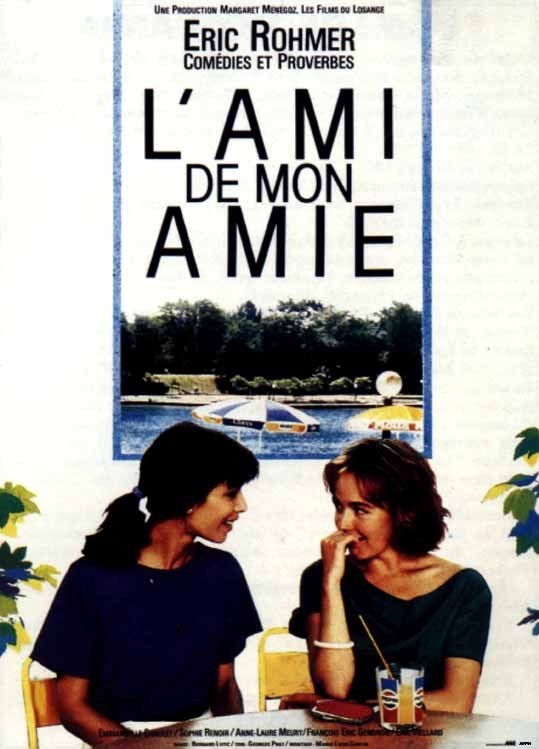

Paris is not all crowded together into a cozy warren of colorful streets, nestled on the banks of the Seine. And Parisians are not all colorful intellectuals, bohemians, artists and tradesmen, so authentic they make you feel like a stage American. France, in fact, is not all like France. Parts of it are glossy new architectural enclaves where yuppies meet to chirp and preen. That is the France of Eric Rohmer’s new film, “Boyfriends and Girlfriends.” The movie takes place in a modern suburb of Paris, so close you can sometimes see the Eiffel Tower in the distance, so far away it is almost another country. This is a clean, well-lighted environment, in which all of the fixtures of a Paris neighborhood have been picked up, shaken well, dusted, sterilized, painted and set down again. The sidewalk cafes, for example, have just the right little porcelain sugar bowls and round white chairs. All they lack is a sidewalk.

In this environment, Rohmer places several young professionals who range in age from, say, 24 to 32. One woman works in a social agency. Another works in a travel bureau. The men have more abstract jobs that require them to venture into Paris itself. But their true home is here in this brand new environment that seems designed to set off their new slacks and sweaters without throwing too much light on their opinions.

“Boyfriends and Girlfriends” is one of a series of “proverbs” that Rohmer has been working through lately, after his earlier series of six “moral tales” such as “My Night at Maud’s” and “Claire’s Knee.” The moral tales presented their characters with actual and tricky moral dilemmas (for example, should one act selfishly on a desire to touch Claire’s knee if that indulgence would interfere with Clair’s otherwise happily innocent existence?). The proverbs, on the other hand, are skimpier affairs, lightweight little whimsies designed to illustrate some sort of everyday truth in an ironic way.

The proverb that inspired “Boyfriends and Girlfriends” is “The friends of my friends are my friends” (which, in French, was the original title of the movie, and, in English, would make a more intriguing one than “Boyfriends and Girlfriends”).

The movie is essentially about bad timing. Two young women are friends, not deep lifelong soul sisters, to be sure, but friends. They see a handsome young man. One likes him, the other gets him, and then, in a sense, they trade, with an additional boyfriend and a few other friends thrown into the mixture. All of the permutations are unimportant, because we are not dealing with the heart here, but with fashion.

There is a sense in which none of these characters can feel deeply, although they can admittedly experience transient periods of weeping and moaning over their cruel fates. That’s because their relationships are based essentially on outward appearances; they choose lovers as fashion accessories. In conversation, they find they have “a lot in common,” but that’s easy to explain: They all hold exactly the same few limited opinions.

When one girl thinks she has a boy and another girl gets him, there is a sense of betrayal, all right, but it’s not the kind of passionate betrayal that leads to murder or suicide. It’s the kind of betrayal that leads to dramatic statements like “I’m not ever going to speak to you again!” Rohmer knows exactly what he is doing here. He has no great purpose, but an interesting small one: He wants to observe the everyday behavior of a new class of French person, the young professionals whose values are mostly materialistic, whose ideas have been shaped by popular culture, who do not read much, or think much about politics, or have much depth. By the end of this film you may know his characters better than they will ever know themselves. In “My Night at Maud’s,” a man sat by the bedside of a woman all night long while they talked and talked and talked. The sad thing about the people in “Boyfriends and Girlfriends,” we sense, is that in such a situation they would have little to talk about. And if the boy actually got into the bed, even less.