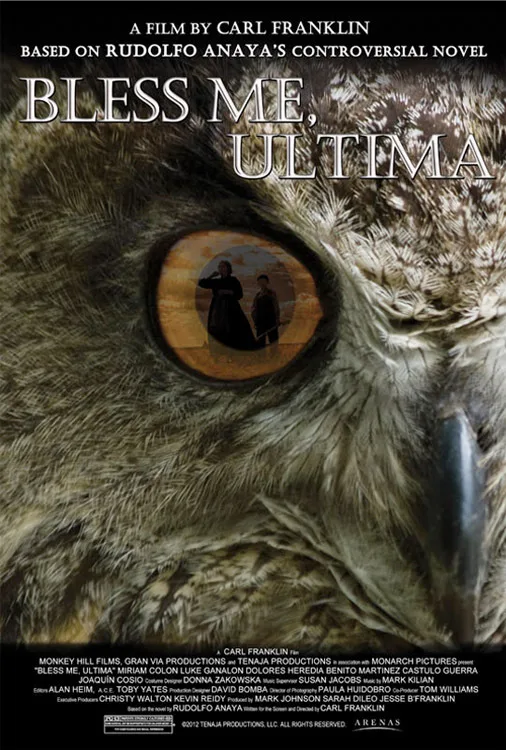

Although it was published only in 1972, Rudolfo Anaya’s “Bless Me, Ultima” has achieved the iconic stature as such novels as “The Grapes of Wrath” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Now comes a movie to do it justice. Carl Franklin’s film is true to the tone and spirit of the book. It is patient and in no hurry. It allows a balanced eye for the people in its hero’s family who tug him one way and another.

The story involves a young boy in a New Mexico town at the end of World War II. With his brothers off to war, his parents invite an elderly relative named Ultima to come and live with them. She possesses magical powers — black powers, say some, who call her a witch. The old woman takes young Antonio under her care. At a time when the traditional culture of New Mexico is under siege from the modern, and young men transformed by war were returning home with strange ideas in their heads, Ultima hopes Antonio can learn his people’s way of living and carry it forward into his life.

I can imagine the pressures that Franklin and his team must have experienced in making the film their way. “Bless Me, Ultima” is filled with elements ripe for exploitation. There are magical spells and demonic possession, and a sequence where Ultima (Miriam Colon) takes along the boy (Luke Ganalon) to gather secret herbs and prepare a potion to drive an evil spirit from the body of another man’s son. The potion works, and after a terrifying struggle, the victim coughs out the spirit, which takes the form of a nasty little globe with wriggling black tendrils, still alive.

We’re close to “Alien” territory here, yet the scene plays out with quiet power. It reflects the film’s essence. Ultima does and says, and Antonio watches in wide-eyed solemnity. Franklin films the vomiting moment from a medium side angle, with the camera at a lowish level, the putrid black ball ending in a hollow of the blankets, its tendrils writhing. Not such a big deal. I imagine a 3-D horror picture spitting the blob into our faces.

“Bless Me, Ultima” is a coming-of-age story that has one hero but two comings of age. Antonio was born in rural territory; his father’s job was on horseback. When the old life died out, his parents moved into Guadalupe, where now his mother seems a better fit. His older brothers want to keep moving, and for them, the war’s draft is an opportunity. We see his favorite brother return, much changed, filled with restlessness and no way to employ it.

Antonio attends Catholic school and is absorbed by the teachings of the church. Ultima seeks to demonstrate that not all answers come from Rome. Antonio is not an active protagonist, striving and deciding. As played by the newcomer Luke Ganalon, his typical role is as a witness, seeing all, saying little, absorbing. That’s an unusual approach to hero-construction.

Yes, things happen to Antonio when Ultima isn’t around. He attends school, walking the same dusty way every morning across a wooden bridge. Franklin establishes the district with an emphasis on the land. Sun, moon, morning stars, the frenzied twists of cactus against the sky. Here is the desert landscape of Cather’s “Death Comes for the Archbishop.” Antonio and his classmates do stuff together. But after he meets Ultima, his life experiences a new tidal pull. There isn’t one second in this film impossible to understand for anyone old enough to see it. There are some scenes of adult behavior difficult for children to understand, but that’s the story of life.

If anyone has trouble understanding “Bless Me, Ultima,” it will be the grown-ups, because so many modern movies have trained them not to understand. Some moviegoers are reeling from the way they’re bludgeoned by the choices they make. Their movies spell everything out, read it aloud to them, hammer it in, communicate by force. This film respects the deliberate nature of time slipping into the future. Sometimes Antonio doesn’t fully realize what’s happened until after it has happened to him. The payoff of a scene is shown in how Antonio’s behavior is reflected in later ones.

The movie is set at a time within current lifetimes. It seems like the ancient past. There’s a night of terror when Antonio and his family are awakened. A mob of men has gathered before the house, many holding torches. This is soon after Ultima expels the evil spirit, and word has raced around. The men say Ultima is a witch and must be turned over to them. Although Antonio’s mother (Dolores Heredia) was most responsible for inviting the old woman to stay with them, it is his father (Benito Martinez) who steps forward in front of his family.

The men carry clubs and firearms. Some are mounted. They don’t crowd the front porch but form a large circle in the yard, which reflects their recognition of the family’s space. Into this space Antonio’s father steps, shirtsleeves rolled up, to ask how dare these men come to his house in the middle of the night and awaken his family. In most movies today, this scene would be quick and ugly. Here, there is time. The mob knows Antonio’s father has a point. It seems logical to them that Ultima must be a witch, so they have a point, too. Much is not understood about witches. The man who had the demon exorcised is still alive. There are pros and cons here.

I like to think of two kinds of men in the mob. Those who eagerly subscribe to the comfort of prejudice, and those who hesitate because they prefer to come to their conclusions in their own ways. “Bless Me, Ultima” has that choice at its center. It says that in the formation of the place now named New Mexico, two peoples came together, the Indians and the Europeans, and formed a population that drew from two traditions. Now we hear of immigration reform. It has to do with taxes and politics. Otherwise, we might as well reform the flights of the birds.