“Bisbee ’17” is a film about a 1917 labor strike against Phelps Dodge, a copper mining company based in Bisbee, Arizona, a town seven miles from the Mexican border. The labor action was cut short when 2,000 strikebreakers and hastily deputized citizens rounded up 1,300 protesters, many of them members of the radical, sometimes violent Industrial Workers of the World, aka The Wobblies. The strikers were taken across state lines by train and dumped in the New Mexico desert with a warning to never return. The event tore apart families and created divisions in Bisbee and the surrounding county that linger to this day. One of the most harrowing anecdotes recounted here finds a sheriff’s deputy arresting his own brother, a striking union member, at gunpoint in his own home.

At the same time, “Bisbee ’17” is a film about many other, related things besides the events themselves—so many things, in fact, that when director-writer-editor Robert Greene cuts to a series of shots of carved-out quarry rock, the multicolored layers stacked up in the frame become metaphors for the movie you’re watching, one of many that “Bisbee ’17 supplies as it goes along.

It’s about labor relations in the United States, a country that prides itself on having a democratic spirit yet has a long history of breaking the back of labor whenever it gets too uppity, and brutalizing and relocating or imprisoning people (including Native Americans and Japanese Americans and now Mexican Americans) who’ve been deemed enemies by the ruling class, which has historically consisted of rich, white, native-born men. (The overwhelming majority of deportees were recently arrived immigrants from Mexico and Europe, and native-born people with socialist, communist or anarchist leanings.)

It’s also about how hard it is to reconstruct the past after first-person witnesses have died. It’s about how history lives on in the imaginations of the descendants of those who were there. And it’s about how the meaning (or “takeaway”) of events depends on the experiences and politics of the people who handed stories down, as well as the viewpoints of descendants, who either pass the stories on intact or make tweaks that reflect their own sense of life.

“Bisbee ’17” is also about the artifice of storytelling and the alchemy of acting, and that magic moment when we decide to forget that we’re seeing performers pretending to be long-dead people, acting out scripted material on sets that aren’t even decorated in period detail, and just roll with the story, as we might roll with a stage production in which a dozen judiciously placed chairs and couple of card tables represent a courtroom.

The movie starts with a wide shot of Richard Hodges, the caretaker of Bisbee High School, standing silently, waiting for Greene’s direction. Another man wanders into the frame and asks what he’s doing; he says they’re shooting a movie and convinces the man to walk offscreen. Then Hodges becomes the first of probably three dozen major witnesses to tell us bits and pieces of the story of the strike. There are many more scenes that start or end this way, and they drive home the idea of stories being in some sense “performed” as people tell them.

Cinematographer Jarred Alterman shoots the movie in CinemaScope dimensions, a wide format more commonly used for action pictures, historical epics and Westerns than documentaries. The town and the surrounding landscape—including the mining company’s fenced-in sites, and the mansion where Walter Douglas, the company’s president, ruled with an iron fist—are sometimes shot with epic flair, as if they’re battlegrounds for gods and warriors, other times as if they’re stage sets waiting to be brought to life by a repertory company. There are scenes where witnesses (or “characters”) seem to be waiting for Greene to cue them to start talking, or listening as he gives instructions.

The movie builds towards an re-enactment of the deportation, with townspeople portraying strikers and strikebreakers. This sequences climaxes with the 1,300 soon-to-be-exiled citizens being forced at gunpoint onto boxcars guarded by rifle-toting snipers. The fear and rage in their faces doesn’t feel like acting. It’s as of they’re channeling the past and letting it possess them.

This section is essentially a self-contained movie-within-a-movie. about a historical play performed on the streets of Bisbee in daylight. It resonates with American atrocities past and present, from the Trail of Tears and the Japanese-American internment to present-day abuses by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE). Most, if not all, of the people we’ve met become participants in this open-air drama, which is recorded by Greene’s camera crew, some of whom are visible in the backgrounds of shots. It’s a bit like watching a fact-based cousin of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town” (with Greene himself acting as the unseen and mostly-unheard stage manager, even though other characters supply the verbal narrating) or Lars von Trier’s “Dogville,” a Wilder-influenced account of a small town living with hideous, suppressed truths.

These are all angles or approaches that Greene has taken many times before, in a career of nonfiction work that has included the likes of “Actress” and “Kate Plays Christine.” His filmography employs self-consciously virtuoso techniques that are more commonly seen in meticulously directed, scripted movies (although the nonfiction films of Errol Morris, a formalist to the bone, are clearly a big influence here). He sometimes indulges in quasi-experimental touches that might briefly make the viewer wonder, “Why is the movie showing me this? Is this a miscalculation or indulgence, or is it leading somewhere?”

To Greene’s credit, in “Bisbee ’17,” there’s a not-always-self-evident purpose behind everything he does with image, sound, editing and performance (an odd word to apply to nonfiction, in most cases—but one that makes sense in films that are explicitly about getting into character in order to imagine past lives). But it’s not a smooth ride by any means. Even at two hours, a slightly longer running time than most theatrical documentaries, “Bisbee ’17” feels overstuffed, rushed, and too eager to jump to the next point when it hasn’t finished developing the last one.

This feels like a case where a simpler (or more “square”) approach early on—say, immediately and concisely laying out the details of the historical event in chronological order, and listing all the major players, rather than doling out tidbits—might have oriented the viewer more quickly, and better paved the way for the detours, flourishes and tricks of perception (such as letting you think that a conversation is present-tense when it’s really two Bisbee citizens running lines, or performing in the film-within-a-film). “Bisbee ’17” moves in fits and starts—by design, it often seems—with major players being introduced with great fanfare (Greene gives movie star entrances to several of them) only to have their narratives cut short after a minute or two, and not rejoined for some time.

But in the second half, the movie’s internal logic belatedly becomes clear. The pieces start to come together. The accumulated details of past and present combine with the emotional weight of all the fragments of stories we’ve heard, and all the different takes on what the strike and deportation meant to Bisbee. And we’re plunged into the thick of the historical re-enactment, with citizens becoming actors in a drama based on fact, re-living the traumas of their ancestors, and coming through the other side feeling as if their pre-existing opinions have been either validated or challenged.

If you’re looking for a clean and forward-moving story that’s mainly interested in delivering a string of facts, this movie is not for you. It’s not one for hand-holding. At times it seems to be on strike against conventional filmmaking itself. But the sheer audacity and originality of the exercise makes it a must-see, regardless of what you might think of the success of failure of any particular choice.

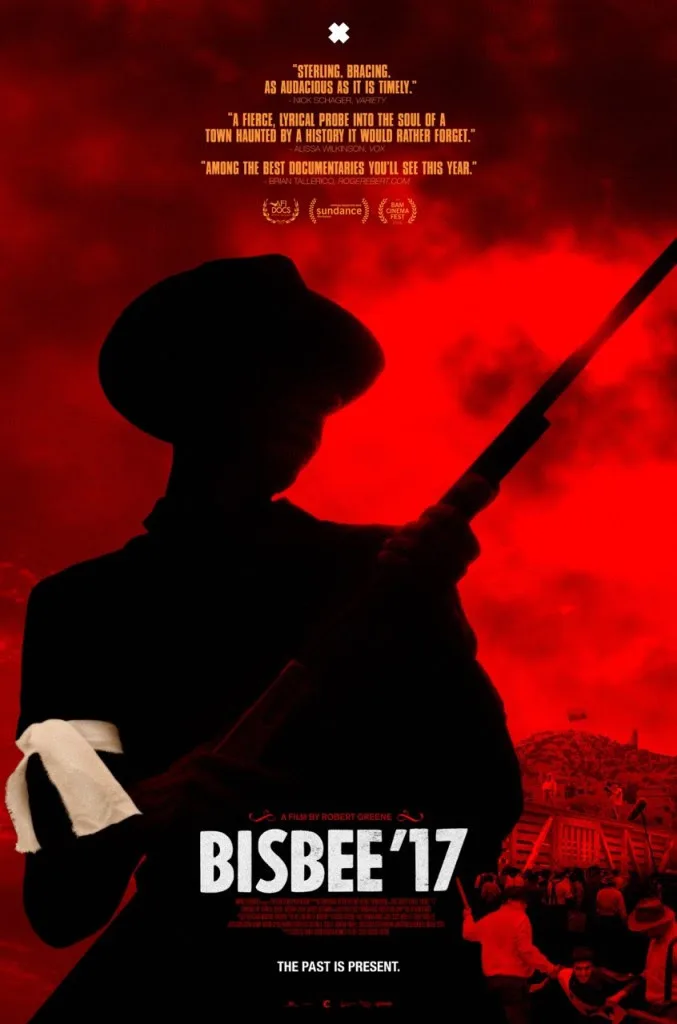

The movie’s guiding spirit is young Fernando Serrano, a lanky Mexican-American actor who plays one of the strikers. His journey teaches him about the history of labor and his own people, and seems to radicalize him. He has the haunted face of a character in a Diego Rivera mural, and unlike a lot of more experienced performers, he seems to have figured out that the best acting often consists of just being in the scene and doing as little as possible, in hopes of serving as a lightning rod or tuning fork for the energy swirling around him. Greene and Alterman keep finding ways to put Serrano in period clothes and place him at the margins of present-tense scenes, often shooting him in partial shadows or hard silhouette, as if he’s a ghost watching us and wondering if we learned anything.