One day in the 1960s, Claude Chabrol, the French director who specializes in the unsavory side of life, was having a drink with Georges Simenon, the writer who had a similar interest in the shadows. Why is it, Simenon asked Chabrol, that movie directors do not make more films without plots? The writer requires a plot in order to start events moving on a blank page. But the director starts with a gift: the human face. A good actor can keep our interest simply by making us wonder who he is, and what he will do next.

At about the time they had their conversation, Simenon wrote the novel Betty, about a woman who walks into a Paris bar out of the rain. Drunk, unhappy, smoking one cigarette after the next, she is picked up by a man who drives her to a seedy bar in Versailles. The man says he is a doctor but is in fact a drug addict; Betty is rescued by a woman in the bar, a rich widow who offers her a bed for the night in a nearby luxury hotel.

There is no plot, but we are hooked. We do not know who Betty is, why she is drunk, who the widow is, or why she is friendly. We learn more about the bar than its patrons. The place is called The Hole, and it is run by a man named Mario who collects the “twisted” – those with something that sets them outside the ordinary. All of the patrons seem to know about each other’s twists.

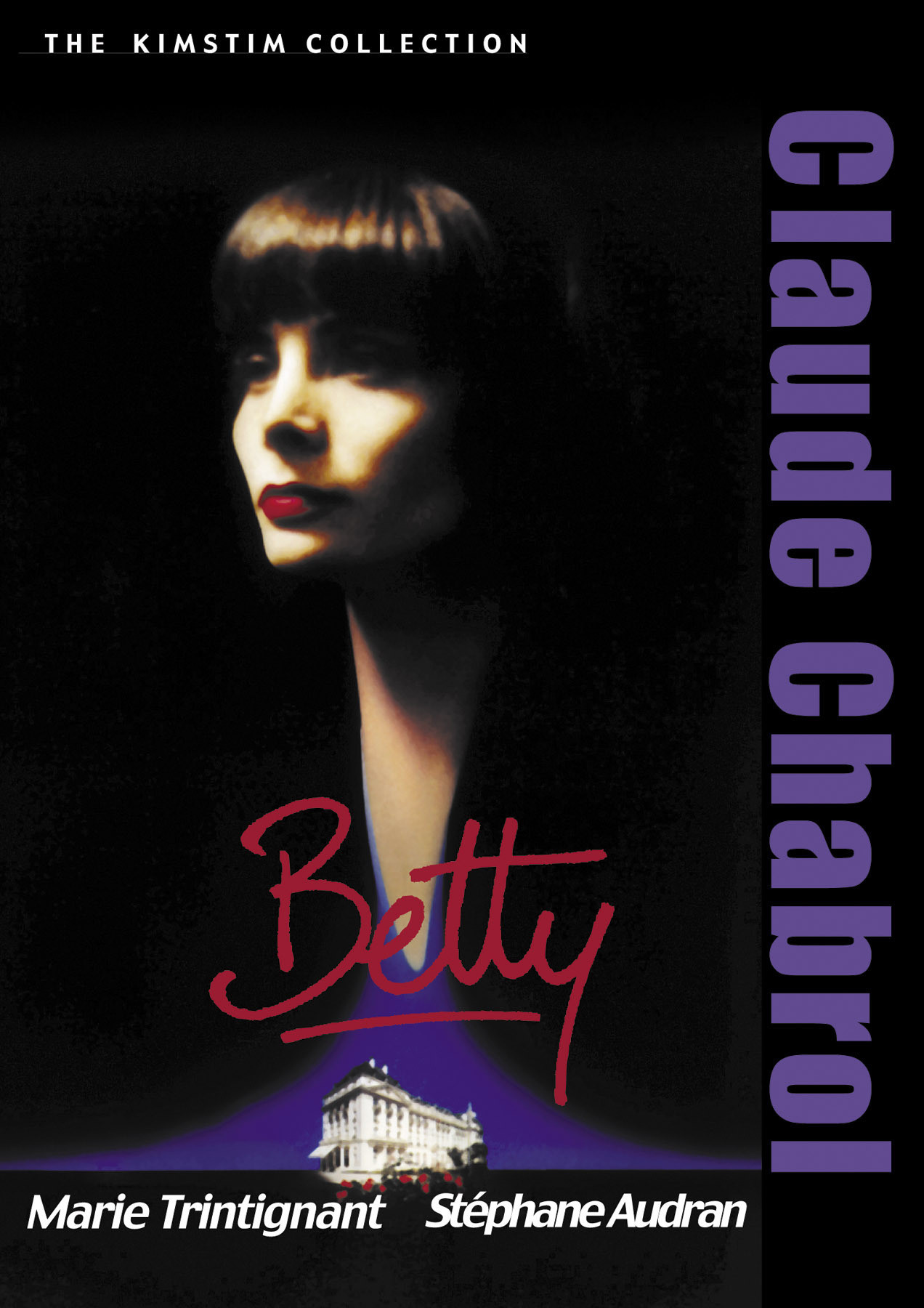

Chabrol’s new film “Betty” is based on the novel. We are able to see how he begins with an actor’s face instead of Simenon’s blank page. The face belongs to Marie Trintignant, whose father is a famous actor and mother a famous director. It is a pretty face – at times seductive and playful – but when we first see her, she is bruised, there are dark circles under her eyes, she looks as helpless as a drowned cat. All she wants to do is drink and smoke and sleep. If a man will buy her drinks, she does not care what happens then.

You see what Simenon meant. We in the audience watch Betty’s face for clues, and listen to every word she says. We wonder about the motives of the older woman, whose name is Laure, and who is played by Stephane Audran, Chabrol’s wife. Is she perhaps a lesbian? No? A lonely woman who wants company? It isn’t that simple. Mario, who runs the bar, is her boyfriend. She seems confident of him.

Surely he would not be attracted by this basket-case named Betty.

Chabrol uses flashbacks to tell us a little of Betty’s story, of her marriage into a rich family that valued her only because her womb could produce heirs. We learn of her drinking, of the reckless sexual behavior that she used to prove she was still free, and of the terrible thing that happened on the rainy night when we saw her for the first time. But there are still surprises, and her destiny is not as inevitable as we may think.

The special gift of this movie is that nothing depends on anything else. It is not necessary that any of the characters meet.

When they do meet, the film supplies them with no obligatory tasks (to fall in love, say, or take a trip, commit a murder, rob a bank).

They have only one responsibility: to do whatever comes next. This creates an entirely different order of suspense from the ordinary “suspense” film.

Watching it, in the same week I saw two conventional Hollywood “thrillers,” was like being invited to participate with the depths my mind instead of just the shallow surface.