“I don’t like you/but I love you.” So went a jukebox hit of the ‘60s, “You Really Got A Hold On Me,” written by Smokey Robinson for him and his group the Miracles and memorably covered by The Beatles. About suffering they were never wrong, the old masters, and so on.

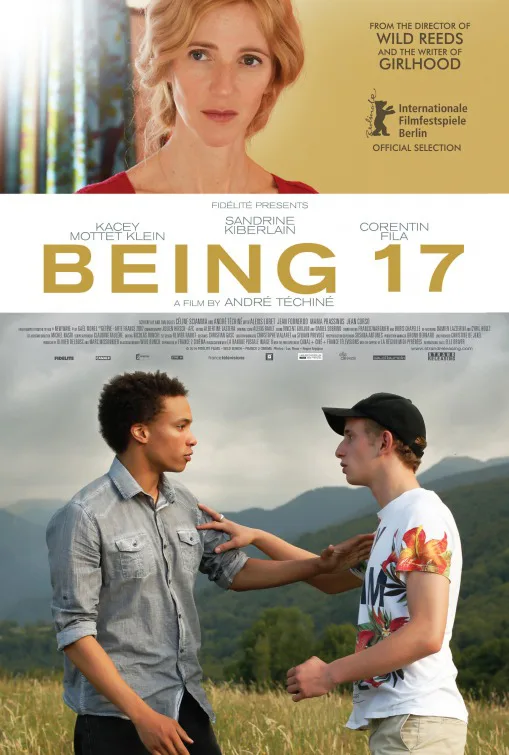

The dislike between Thomas and Damien, the teen protagonists of the latest film by French master André Téchiné, is plain and real enough. Whether it’s masking “love” is ultimately open to question, but what it barely masks is a raw erotic magnetism. Damien (Kacey Mottet Klein) is a pale, gangly scholarly type who’s got a relatively cushy life in a very scenic mountain village. His dad is away in the army (he’s a pilot) and his doctor mother (Sandrine Kiberlain) is a do-gooder around the neighborhood. One way she helps out the community is by inviting Thomas (Corentin Fila), a mixed-race adopted kid from a less privileged family whose mother is ill, to live in the house with her and Damien. Bad move: Thomas and Damien, who despite differing characteristics occupy comparably low rungs on their school’s status ladder, have been shoving and kicking and fighting each other most of the winter term at school.

Once they’re thrown into the same environment, something’s gotta give. Discovering one’s sexuality is a different deal in the 21st century than it has been in older coming-of-age films. And Téchiné, despite being 70, shows a sharp eye not just for how young people of today dress and accessorize, but how they carry themselves. For this film he’s enlisted “Girlhood” director Céline Sciamma as a co-writer, and working with the younger filmmaker certainly must have helped. But this isn’t a film that makes a big deal of its contemporary authenticity; it wears its carefully measured elements lightly, the better to shine a light on its intriguing characters.

The film’s scenario (“freely adapted,” according to the credits, from a 2008 French TV movie titled “New Wave,” written and directed by Gael Morel, a former protégé of Téchiné’s) is not free of cliché; the second act trauma (while I normally hesitate to divide movies up into acts, because cinema isn’t theater, this movie invites the practice by explicitly dividing the action between three discrete school terms) is relatively predictable given the positions of the players. But by the same token it doesn’t resolve predictably. The movie saunters along with a kind of stoic naturalism that makes even the catastrophic events that befall the characters things to be coped with and worked through rather than world-enders. The assured cinematography of Julien Hirsch, using a lot of handheld camerawork but always maintaining firm control of a particular, unobtrusive point of view, contributes to the easy feel. The original score by Alexis Rault strikes moodily appropriate, lyrical and elegiac notes with discretion, and a repeated song by the late Burkinabé musician Victor Démé is beautiful and haunting.

“Need is part of nature … desire is not of natural origin. It is superfluous.” So goes a reading in one of Thomas and Damien’s school assignments. The project of “Being 17,” which is realized via the accretion of dozens of wonderful details, is to prove that assertion entirely wrong, to celebrate desire as the most natural and necessary thing in our lives.