Born into crushing poverty in pre-Castro Cuba, young Reinaldo Arenas was told by a teacher than he had a gift for poetry. When his grandfather heard this news, he slammed his fist down on the table and beat the boy. That more or less sets the pattern for Arenas’ life: He tries to exercise his gifts as a poet and a novelist, and society slaps him down. It doesn’t help that he’s a homosexual.

Arenas believed the great betrayal in his life was by Fidel Castro. As a teenager, Reinaldo hitchhiked to the hills and joined the revolution, but once Castro came to power he showed little sympathy for artists and none for homosexuals. Arenas was an outcast and for seven years a prisoner in Cuba — until 1980, when he took advantage of the boat exodus for criminals, gays, the mentally ill, and others considered unfit to be Cubans. Ten years later, in Manhattan, dying of AIDS, he committed suicide, using pills and (just to be sure) a plastic “I Love NY” bag over his head.

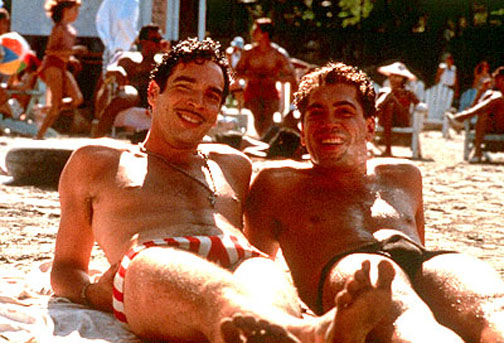

“Before Night Falls” tells the story of Arenas’ life through the words of his work and the images of Julian Schnabel’s imagination. Schnabel, the painter, makes his screen a rich canvas of dream sequences, fragmented childhood memories, and the wild Cuban demimonde inhabited by Arenas and others who do not conform. There is no sequence more startling than one where Arenas stumbles onto a ragtag commune of refuseniks and finds that in the roofless ruin of an old cathedral they are building a hot-air balloon with which they hope to float to Florida. The balloon actually makes one brief flight. Did this episode actually happen? I would like to think that it did.

This is Schnabel’s second film, and his second about an artist who is also a moody, difficult outcast. The first film was “Basquiat” (1996), about Jean Michel Basquiat, the Manhattan graffiti artist who rose briefly from homelessness to fame before sinking into madness. Arenas describes a similar trajectory. For both men, joy seems to come primarily at those moments when they are actually creating. Sex (for Arenas) and drugs (for Basquiat) are a way to avoid work, loneliness and pain, but they lead to trouble, not release. Arenas claimed to have slept with 5,000 men by the age of 25. That is not the record of a man who finds sex satisfying, but of one who does not.

Arenas is played by Javier Bardem, a Spanish actor with a specialty in macho heterosexuality (if you doubt me, see “Jamon, Jamon”). He doesn’t play Arenas as a gay man so much as a man whose body fits like the wrong suit of clothes. We accept Arenas as gay in the movie because the story says he is, and because there are after all no rules about how a homosexual should look or behave — but there is somehow the feeling that the movie’s Arenas is not gay from the inside out, but has chosen the lifestyle as part of a compulsion to defy Castro in every way possible.

The film contains two more convincing homosexual characters, both played by Johnny Depp: Lt. Victor, a sleek, tight-trousered military officer, and “Bon Bon,” a flamboyant transvestite who struts through Castro’s prisons and proves incredibly useful by smuggling out one of Arenas’ manuscripts, concealing it in that place where most of us would be most inconvenienced by a novel, however brilliant.

What is most heroic about Arenas is his stubbornness. He could make his life easier with a little discretion, a little cunning, a little tact, and even a small ability to tell the authorities what they want to hear. There must have been a lot of gay men in Cuba who didn’t make their lives as impossible as Arenas did. Consider the character of Diego, in “Strawberry and Chocolate,” the 1995 movie by the great Cuban director Tomas Gutierrez Alea. The movie is set in 1979, Diego is clearly gay, and yet he lives more or less as he wants to, because he is clever and discreet.

There is a little something of the spoiled masochist about Arenas. One would not say he seeks misery, but he wears it like a badge of honor, and we can see his mistakes approaching before he does. This is not a weakness in the film but one of its intriguing strengths: Arenas is not presented as a cliché, as the heroic gay artist crushed by totalitarian straightness, but as a man who might have been approximately as unhappy no matter where he was born.

That angle between Arenas and his society is perhaps what inspired his work. Trapped on the margin, he wrote in spite of everything, and the anguish of creation was a source of energy. One is reminded a little of the Marquis de Sade, as portrayed in “Quills.” It was never simply what they wrote, but that, standing outside convention, taunting the authorities, inhabiting impossible lives, they wrote at all.