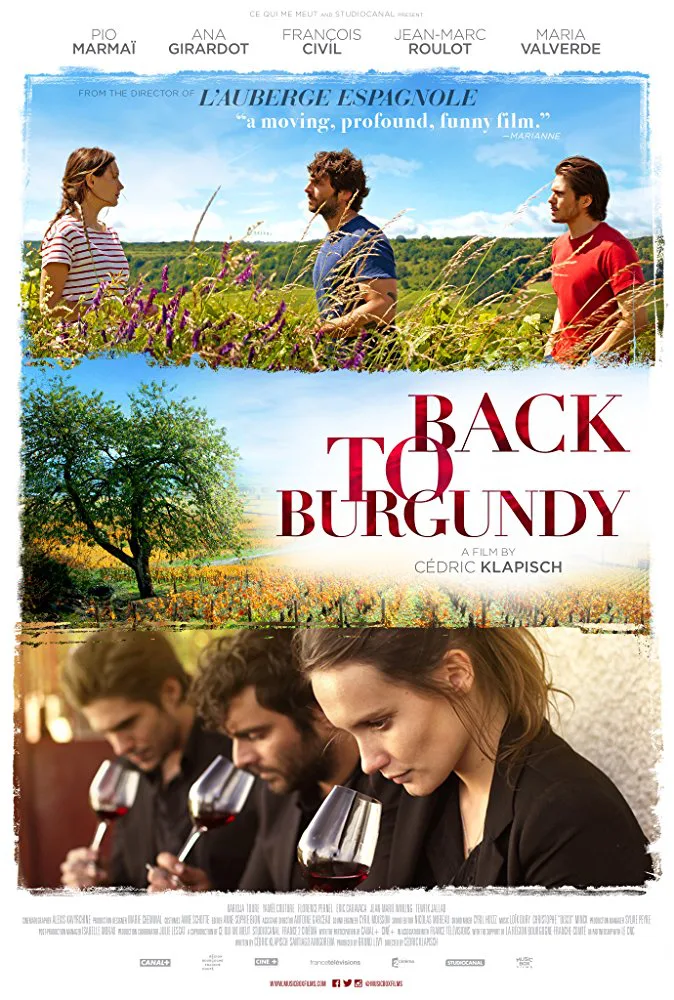

In “Red Obsession,” a documentary about the wine industry in France’s Bourdeaux region, Francis Ford Coppola describes drinking a glass of wine that had been bottled four years after the French Revolution. “Wine tells a story,” says Coppola, who wonders if Thomas Jefferson or the Marquis de Lafayette had had a glass of the same wine. The story-telling power of wine is the context of Cédric Klapisch’s “Back to Burgundy,” a film detailing a year in the life of a fictional wine-making family in Burgundy. The taste of the family wines propel the characters back into the past, wrinkling up time for the characters. “Back to Burgundy” has a gentle low-stakes mood (although the actual stakes are often quite high), and the script (also by Klapisch) is episodic in structure. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t. When the film focuses on the wine-making process, in the progression from vine to bottle, it’s a fascinating and detailed look at a very specific subculture.

When his father becomes ill, Jean (Pio Marmaï) returns home to the family vineyard in France after 10 years abroad. There has been little to no contact between Jean and his two siblings, Juliette (Ana Girardot) and Jérémie (François Civil). When their father dies, the siblings must make some serious decisions about the family business. Unable to pay the huge inheritance tax, they consider their options. They could sell the vineyard to pay the tax. They could rent out part of it. Jérémie has married into another wine-making family, and it’s expected he will step up to be a partner in his father-in-law’s business. Jean, with a girlfriend and son back in Australia, has no intention of staying in France. That leaves Juliette. It’s now up to her to make the decisions for the upcoming harvest, and she doesn’t have her father to consult.

When Jean, Juliette and Jérémie were children, their father would blindfold them and make them taste the family wines, quizzing them. “Behind the lemon, is there another fruit?” he asks. Juliette was always the best at this game. Their dead father (Éric Caravaca) haunts the film, in flashbacks but also sometimes literally. Jean converses and argues with the ghost of his dead father, similar to how the ghost of the father was used in HBO’s “Six Feet Under.” Like Jean, Nate in “Six Feet Under” is the son who left, who refused the father’s legacy. But unlike “Six Feet Under,” where the presence of the father’s ghost was a constant, woven into the fabric of the show, “Back to Burgundy” uses the device indifferently and intermittently. There’s no commitment to the trope, leading to a slightly cheesy result. The same is true for the moments when time folds in on itself, and the child versions of Jean, Juliette and Jérémie surge into the frame where the adults are now standing. If the film had a more frankly poetic and symbolic structure, if it was less literal, these devices might have had more thematic reverb.

Where the film is on firmest ground is in specifics of the culture of wine-making: the seasonal workers showing up, the rowdy parties at the end of the harvest, the taste-testing during the fermenting process, the worried glances at the sky, the obsessive checking of Weather Apps. In these sequences, the film really knows what it is doing, knows what it wants to say and convey. There’s a whole section where Juliette has to throw around her weight as the boss for the first time, and publicly reprimands one of the seasonal workers for initiating a grape-fight in the fields. He pushes back against her authority. This altercation has an unexpected denouement later on, and unlike many of the other sequences, this one sparks with life, spontaneity, the unexpected.

Each sibling has a specific emotional arc. Jean stays on in France longer than he had planned, to help with the upcoming harvest, causing strife with his girlfriend and son back home. Juliette is thrust into the leadership position of the vineyard. Jérémie is infantilized by his new in-laws, and needs to make a stand as his own man. Some of these plot-lines are interesting, some are drawn out into practically slow-motion lengths, almost the way sub-plots are elongated during a season of television. The language is often so on-the-nose it’s shocking it wasn’t excised at some point in the process. (Jean saying in Voiceover: “Love is like wine. It takes time. It needs to ferment” is just one example.)

The episodic quality of the script shows its awkward skeleton in the sequences where one scene presents a problem or conflict which is then resolved or answered in the next scene. Jean, in a fit of frustration, exclaims he doesn’t care about the family vineyard at all, the land can go to hell as far as he’s concerned. In the very next scene, Jean catches a neighboring farmer spraying pesticides on an area overlapping with the family vines, and flies off the handle. His girlfriend (María Valverde), visiting from Australia, comments, “I guess you do care about the land after all.” Along with the in-your-face music creating a mood so insistently that scenes barely have a chance to breathe, “Back to Burgundy” wants to make sure we get the connections. Proust’s madeleine never worried so much.

Still, “Back to Burgundy” has much in its favor. The three main actors create a believable sense of the kind of intimacy and silliness and intensity adult siblings often share. This is easier said than done. Juliette’s journey into the light as the real wine-maker of the family, the natural inheritor of her father’s legacy, is—in its way—the most satisfying arc in this film of many arcs. At every step of the way, she is forced to make decisions, decisions which had always been her father’s call in the past. Are the grapes ready to be harvested? Is it time to stop the fermenting process? Sometimes she just doesn’t know. In a family where tradition is everything, where things have been done the same way for generations, her decision to go with her own nose—to decide what kind of wine she wants to make (as opposed to trying to replicate what she thinks her father would do) is a quietly feminist act. It’s the only arc in “Back to Burgundy” not underlined obsessively by music and voiceover dialogue, but it’s the arc that left the most pleasing aftertaste.