I believe you can go to school to learn to be an accountant, a doctor, a physicist, an engineer, an astronaut. I am not sure you can learn to be an artist. Artists are born, not made, and the real reason to study the arts is to have fun, learn technical skills, network with other creative types, fall in love with people who are not boring, and do the work you probably would have done anyway. That said, I highly recommend college. I majored in English and journalism, and wanted to be a graduate student forever.

I am writing this the morning after my wife and I attended the Head to Toe gala at which students of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago presented their spring fashion show. We saw about half of the work presented a week earlier at the school’s 2006 Fashion Show at Marshall Field’s, which sounds ever so much more upscale than the 2007 Fashion Show at Macy’s. I was astonished. The creativity and wit in their designs would have made Fellini envious. These were not items of clothing; these were visual arts. I could imagine the same models, wearing the same designs, walking up the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival and sending the designers of Paris weeping and gnashing into the shadows.

Then we learned the first third of the show, featuring white clothing, was all by freshmen. They didn’t learn to create those fashions between September and now. Therefore, apparently, they always could design. I am not suggesting the school’s faculty serves no purpose; indeed, as a teacher of film appreciation, I believe faculties in the arts are sainted. They must guide, advise, moderate, encourage, teach methods, provide a context, share secrets and declare an informed opinion on the worth of the work. They create a world within which such work is possible and valued. What they cannot do, I suspect, is teach a student how to be original and creative.

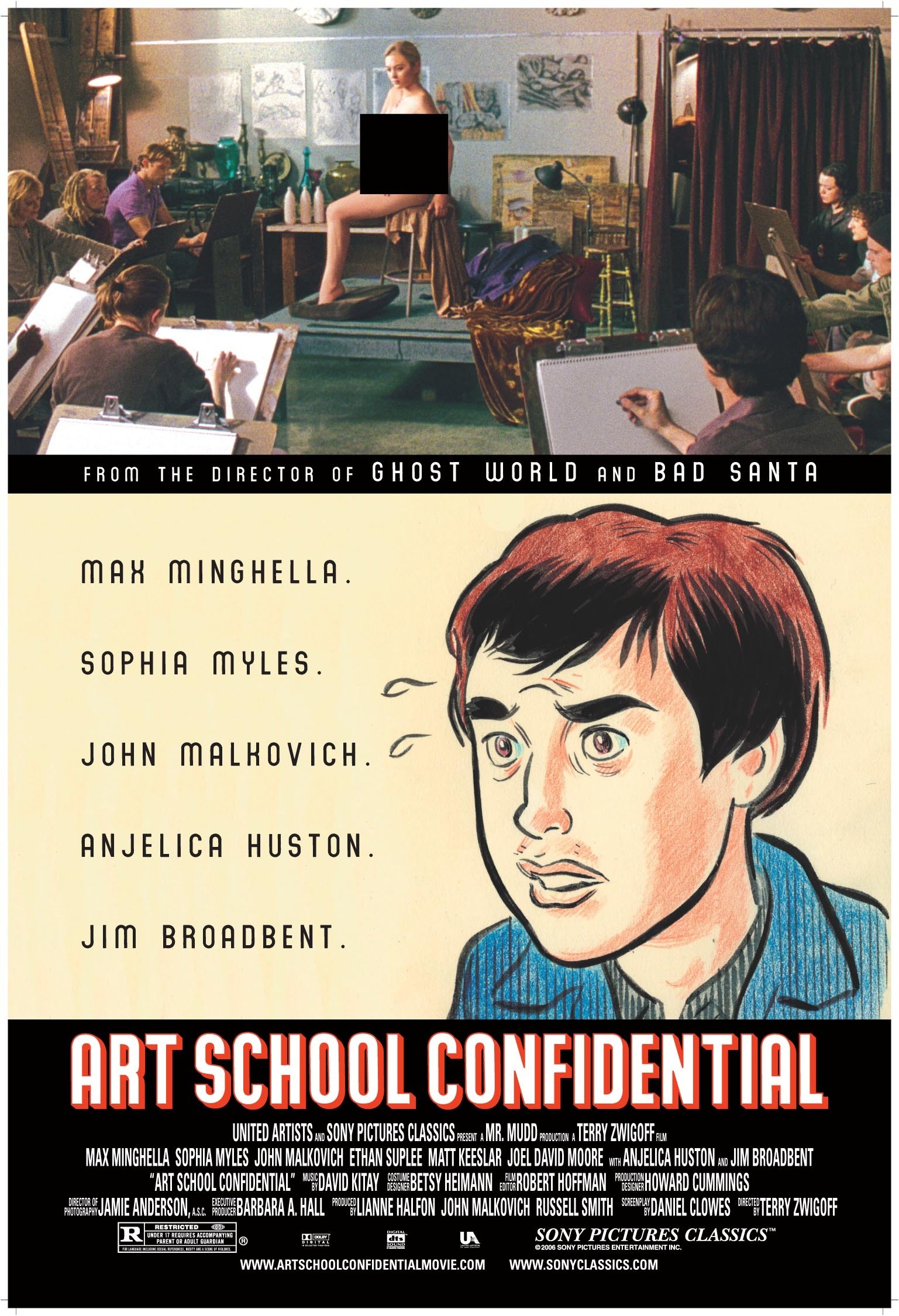

“Art School Confidential,” the new comedy by Terry Zwigoff, seems to share these sentiments. It was written, like his “Ghost World,” by the artist Daniel Clowes and based on one of Clowes’ graphic novels. Zwigoff also made the great documentary “Crumb,” about another artist who is entirely his own creation. The movie’s hero is Jerome (Max Minghella), already an extraordinary draftsman when he enters the school; his drawings glow from the page with conviction and love. “I want to be the next Picasso,” he claims, which indicates his vision is indeed inward and personal, since he does not know enough about Picasso to see that his work does not have a single line in common with that master. Perhaps he simply means he wants to be famous, make lots of money and grow old while making love to beautiful women. Honorable goals.

There is a moment in the film when the students are asked to create a self-portrait. Jerome’s work bears comparison with the Pre-Raphaelites. The student whose self-portrait is most highly praised has created an assemblage of lines and squiggles that “looks like a Cy Twombly,” someone says — in praise. I’m not saying a 19th century representational style is superior to Twombly, but I do believe that in a freshman class, the purpose of a self-portrait assignment is to draw something that looks like it might be you. Students have to learn to walk before they can crawl.

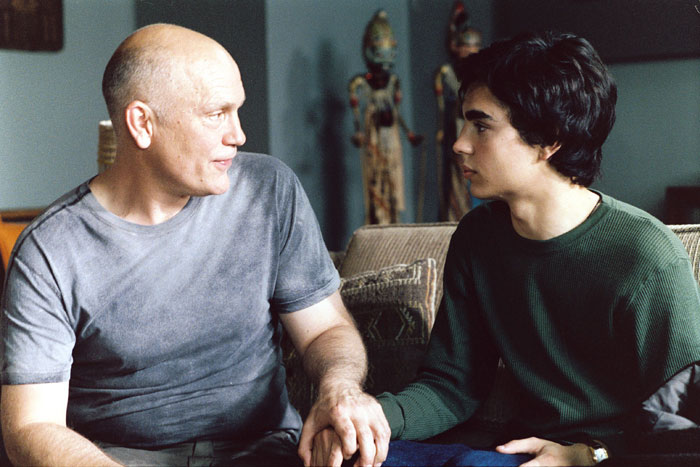

Jerome’s teacher is Professor Sandiford (John Malkovich), who paces the classroom talking on his cell phone, trying to get a gallery to give him a show. Sandiford draws triangles. “I was one of the first,” he says, to paint triangles. In his mind, perhaps second only to Euclid. Malkovich’s character issues dire warnings about the future awaiting any would-be artist, conceals rage about his own neglect, and in general provides the kind of forbidding detachment that drives students crazy trying to please him.

Jerome falls in love with the artists’ model Audrey (Sophia Myles). She likes the drawing he does of her, as who would not, and is kind to him, and as a nerd in high school he is thrilled that his talent has at last brought him the affection of a beautiful girl. Jerome’s roommates are Vince (Ethan Suplee) and Bardo (Joel David Moore), who like all roommates (in the words of John D. McDonald) deprive him of solitude without providing him with companionship. The Vince character is a wonderful creation, an unkempt underground filmmaker, making a work of enthusiasm and incoherence; much of his time is spent rearranging 3 x 5 cards describing hypothetical scenes. Bardo is helpful on practical stuff, explaining the politics of the Strathmore school of art and briefing Jerome on his fellow students.

There is a wise and understanding teacher on the faculty, played by Anjelica Huston. Defending the work of Dead White Males, she sensibly observes that when they did their best work “they weren’t dead yet.” Even more wisdom, and certainly more weariness, come when Jerome visits the squalid apartment of the drunken old artist Jimmy (Jim Broadbent), who might once have been young and might once have had hopes, but now festers in cynicism, anger, despair and the need for a drink. There is something in the Zwigoffian universe that values such characters; having abandoned all illusions, they offer the possibility of truth. I also much enjoyed Broadway Bob (Steve Buscemi); his cafe is a hangout for the students, who hope he will hang their work on his walls. Bob at this point is more important to them than the art critic of the New York Times.

Now I must regret to tell you the plot also involves a serial killer who is stalking the campus and has claimed several victims. The police investigate, the students become paranoid and some of the characters fall under suspicion. There is nothing particularly wrong with this subplot, except that it is completely unnecessary, and imposes a generic story structure on a film that might better have just grown from scene to scene like an experience. I wasn’t interested in the killer and would have rather seen more of Jerome interacting with his professors, with Broadway Bob and old Jimmy, and with the beautiful Audrey, who will surely see that her future lies with the next Picasso, since she was born too late to lie with the previous one.