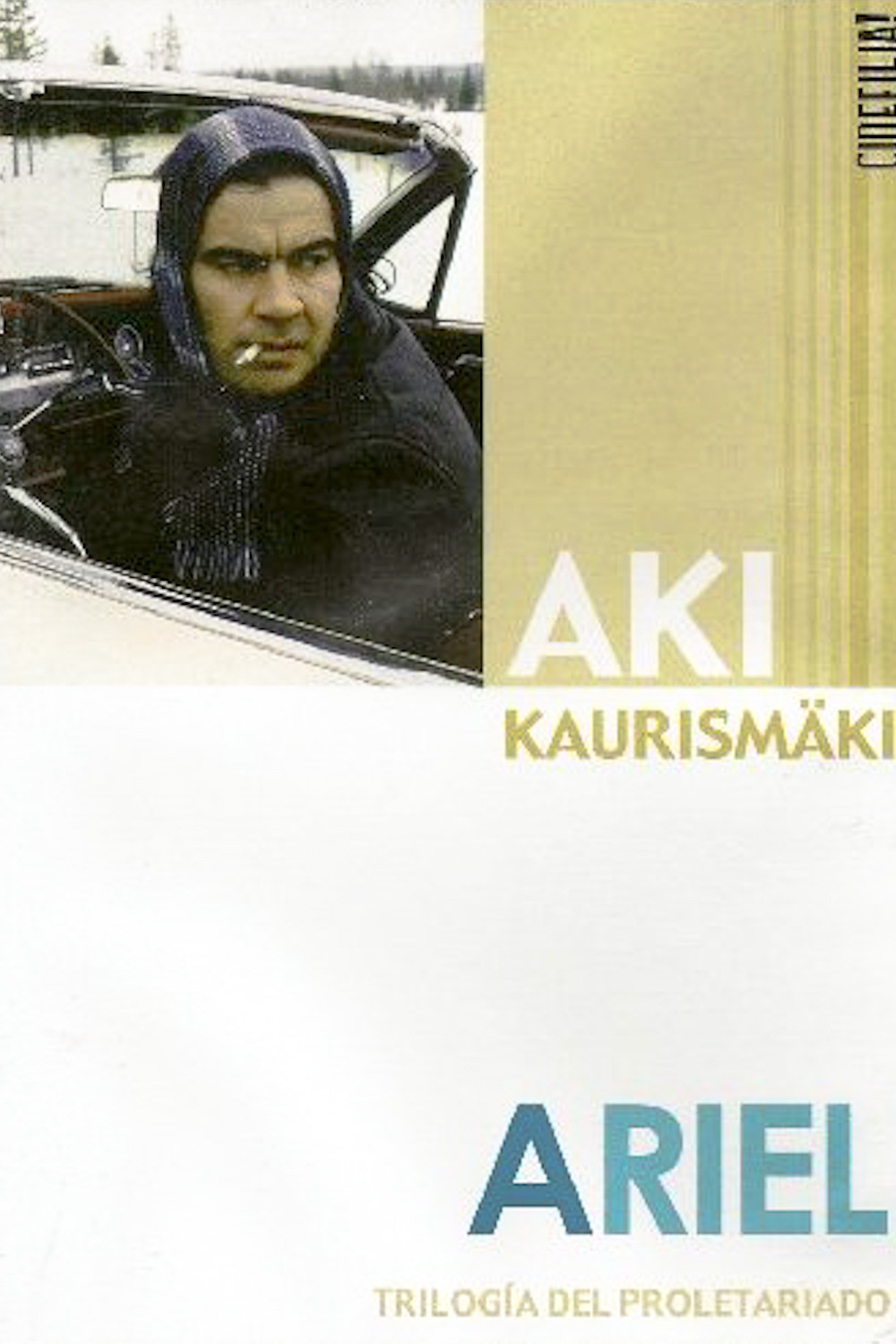

Ingmar Bergman made a film at the dawn of his career named “It Rains on My Future,” and I thought of that title while I was watching “Ariel.” This is the new film by Aki Kaurismaki, the director from Finland whose work has been winning festivals and inspiring articles in film magazines calling him the best young director from Europe. I went expecting to see the new Fassbinder or Herzog or Almodovar, and what surprised me was how traditional the film is; it’s a despairing film noir with a “happy” ending that taunts us with its irony.

The story involves Taisto, a miner from northern Finland who loses his job when the mine closes. He sits in a cafe with a depressed friend who gives him his old Cadillac convertible and then walks into the men’s room and blows his brains out. Taisto drives the convertible to southern Finland, where he is quickly relieved of his life savings by muggers. He gets a day-labor job, gets a bed in a Skid Row mission, and then strikes up an instant romance with a metermaid, who throws away her parking tickets and goes for a ride in the Cadillac.

Meeting the metermaid is a stroke of luck for Taisto, but life is not going to be kind to him, and the plot of “Ariel” involves one crushing misfortune after another. It’s like one of those 1940s B movies – “Detour,” maybe – where the hero tells you on the soundtrack that his luck is always rotten, and the story proves that he’s right.

One of the special qualities of the movie is the physical clumsiness of most of the characters. They move like real people, not like the smoothly choreographed athletes we see on TV and in American movies. When the hero runs, he looks like he’s not accustomed to running. When cops race up to nab somebody, they run flat-footed, and grab him in an awkward and uncoordinated tussle.

A similar clumsiness adds conviction to the action. Events occur in a stark and naive way. A bank robbery ends with money being dropped all over the sidewalk. Conversations are blunt. Motives are simple. The movie’s lack of physical and social finesse is a positive quality; it makes the characters seem touchingly real. Watching their clumsiness, I became aware of how actions sometimes don’t seem spontaneous in Hollywood films. Nobody ever seems to be performing an action for the first time, and the moves all seem practiced and familiar.

The hero of “Ariel” is played by Turo Pajala, an actor who bears a passing resemblance to Bruno S., the star of Herzog’s “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser.” He projects the qualities of a congenital victim, a man so overwhelmed by the relentless malice of the universe that he’s punch-drunk with bad luck. The movie surrounds him with people who are on the same wavelength. Misfortune is their companion. The strongest character in the movie is the metermaid’s young son, who keeps his nose stuck in comic books and accepts his roller-coaster life with stoic calm.

“Ariel” is the first film of Kaurismaki’s I’ve seen, and on the basis of it I want to see more. He has a particular vision. It isn’t the vision of a flashy stylist with fashionable new attitudes, but the vision of a man who has found a filmmaking rhythm that suits his own bruised sensibility. “Ariel” speaks for the dispossessed with a special conviction because it isn’t even angry. It’s too tired to be angry. It’s resigned. The more you think about it, the last scene, the “happy” ending, may be the only really angry scene in the movie.