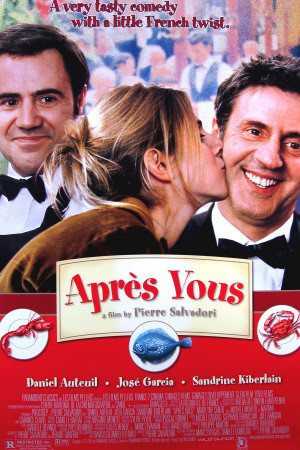

Daniel Auteuil, who seems to be the busiest actor in France right now, has that look about him of a man worried about whether he is doing the right thing. In “Apres Vous” he does the right thing and it results in nothing but trouble for him. He rescues a man in the act of committing suicide, and then in an irony which is probably covered by several ancient proverbs, he feels responsible for the man’s life.

Auteuil plays Antoine, the maitre d’ at a Paris brasserie, which, if the customers typically endure as much incompetence as they experience during this movie, must have great food. Taking a short cut through a park late one night, Antoine comes upon Louis (the sad-eyed, hangdog Jose Garcia), just as he kicks the suitcase out from under his feet to hang himself from a tree. Antoine saves him, brings him home, introduces him to his uneasy girlfriend Christine (Marilyne Canto), and cares more about Louis than Louis does.

Louis, in fact, wishes he had committed suicide. He is heartbroken over the end of his romance with Blanche (Sandrine Kiberlain), and suddenly remembers he has written a letter bidding farewell from life and mailed it to the grandmother who raised him. Antoine promptly drives through the night with him to intercept the letter, and finds himself living Louis’ life for him.

“Apres Vous” is intended as a farce, but lacks farcical insanity and settles for being a sitcom, not a very good one. One problem is that neither Louis nor his dilemma is amusing. Another is that Antoine is too sincere and single-minded to suggest a man being driven buggy by the situation; he seems more earnest than beleaguered.

Farces often involve cases of mistaken or misunderstood identities, and that’s what happens this time as Antoine seeks out Blanche, finds her in a florist shop and falls in love with her. That would be a simple enough matter, since after all she has already broken up with Louis, but Antoine is conscientious to a fault, and feels it is somehow his responsibility to deny himself romantic happiness and try to reconcile Louis and Blanche. Since there is nothing in the movie to suggest they would bring each other anything but misery, this compulsion seems more masochistic than generous.

Much of the action centers on the brasserie, Chez Jean, where I would like to eat the next time I am in Paris, assuming Louis and Antoine no longer work there. Louis gets Antoine the wine steward’s job, despite Antoine’s complete lack of knowledge about wine; he develops a neat trick of describing a wine by its results rather than its qualities, recommending expensive labels because they will make the customer feel cheery. This at least has the advantage of making him less boring than most wine stewards.

Blanche, meanwhile, doesn’t realize the two men know each other, and that leads of course to a scene in which she finds that out and feels betrayed, as women always do in such situations, instead of being grateful that two men have gone to such pains to make her the center of their deceptions. There are also scenes that I guess are inevitable in romantic comedies of a certain sort, in which one character and then another scales a vine-covered trellis to Blanche’s balcony, risking their lives in order to spy on her. I don’t know about you, but when I see a guy climbing to a balcony and his name’s not Romeo, I wish I’d brought along my iPod.

There is a kind of mental efficiency meter that ticks away during comedies, in which we keep an informal accounting: Is the movie providing enough laugher to justify its running time? If the movie falls below its recommended laughter saturation level, I begin to make use of the Indiglo feature on my Timex. Antoine and Louis and Blanche make two or three or even four too many trips around the maypole of comic misunderstandings, giving us time to realize that we don’t really care how they end up, anyway.