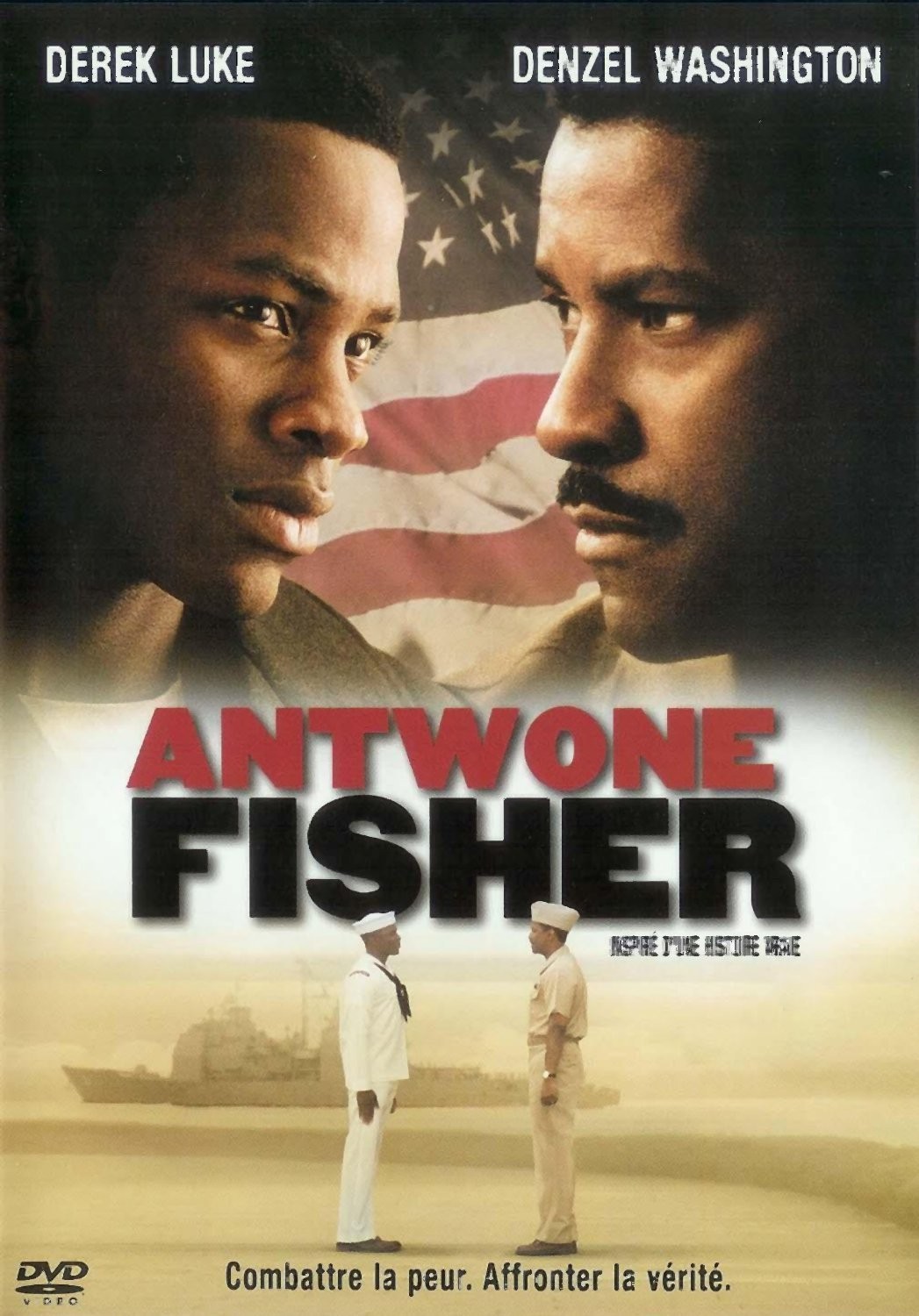

Antwone Fisher is a good sailor but he has a hair-trigger temper, and it lands him in the office of the base psychiatrist, Dr. Jerome Davenport. He refuses to talk. Davenport says he can wait. Naval regulations require them to have three sessions of therapy, and the first session doesn’t start until Antwone talks. So week after week, Antwone sits there while the doctor does paperwork, until finally they have a conversation: “I understand you like to fight.” “That’s the only way some people learn.” “But you pay the price for teaching them.” This conversation will continue, in one form or another, until Fisher (Derek Luke) has returned to the origin of his troubles, and Davenport (Denzel Washington) has made some discoveries as well. “Antwone Fisher,” based on the true story of the man who wrote the screenplay, is a film that begins with the everyday lives of naval personnel in San Diego and ends with scenes so true and heartbreaking that tears welled up in my eyes both times I saw the film.

I do not cry easily at the movies; years can go past without tears. I have noticed that when I am deeply affected emotionally, it is not by sadness so much as by goodness. Antwone Fisher has a confrontation with his past, and a speech to the mother who abandoned him, and a reunion with his family, that create great, heartbreaking, joyous moments.

The story behind the film is extraordinary. Fisher was a security guard at the Sony studio in Hollywood when his screenplay came to the attention of the producers. Denzel Washington was so impressed he chose it for his directorial debut. The newcomer Derek Luke, cast in the crucial central role after dozens of more experienced actors had been auditioned, turned out to be a friend of Antwone’s; he didn’t tell that to the filmmakers because he thought it would hurt his chances. The film is based on truth but some characters and events have been dramatized, we are told at the end. That is the case with every “true story.” The film opens with a dream image that will resonate through the film: Antwone, as a child, is welcomed to a dinner table by all the members of his family, past and present. He awakens from his dream to the different reality of life on board an aircraft carrier. He will eventually tell Davenport that his father was murdered two months before he was born, that his mother was in prison at the time and abandoned him, and that he was raised in a cruel foster home. Another blow came when his closest childhood friend was killed in a robbery. Antwone, who is constitutionally incapable of crime, considers that an abandonment, too.

As Antwone’s weekly sessions continue, he meets another young sailor, Cheryl Smolley (Joy Bryant). He is shy around her, asks Davenport for tips on dating, keeps it a secret that he is still a virgin. In a time when movie romances end in bed within a scene or two, their relationship is sweet and innocent. He is troubled, he even gets in another fight, but she sees that he has a good heart and she believes in him.

Davenport argues with the young man that all of his troubles come down to a need to deal with his past. He needs to return to Ohio and see if he can find family members. He needs closure. At first Fisher resists these doctor’s orders, but finally, with Cheryl’s help, he flies back. And that is where the preparation of the early scenes pays off in confrontations of extraordinary power.

Without detailing what happens, I will mention three striking performances from this part of the movie, by Vernee Watson-Johnson as Antwone’s aunt, by Earl Billings as his uncle, and by Viola Davis as his mother. Earlier this year, Davis appeared as the maid in “Far from Heaven” and as the space-station psychiatrist in “Solaris.” Now this performance. It is hard to believe it is the same actress. She hardly says a word, as Antwone spills out his heart in an emotionally shattering speech.

Antwone’s story is counterpointed with the story of Dr. Davenport and his wife, Berta (Salli Richardson). There are issues in their past, too, and in a sense Davenport and Fisher are in therapy together. There is a sense of anticlimax when Davenport has his last heartfelt talk with Antwone, because the film has reached its emotional climax in Ohio and there is nowhere else we want it to take us. But the relationship between the two men is handled by Washington, as the director, with close and caring attention. Hard to believe Derek Luke is a newcomer; easy to believe why Washington decided he was the right actor to play Antwone Fisher.