Don’s antique shop, in “American Buffalo,” has become one of the fundamental spaces of the stage, like Willy Loman’s kitchen and Lear’s blasted heath and the place, wherever it is, where they wait for Godot. In it, David Mamet created a long day and night in which Don and Teach, and later Bobby, restlessly waited and talked about a job they were going to do, while they uneasily wondered if they should, or could, do it.

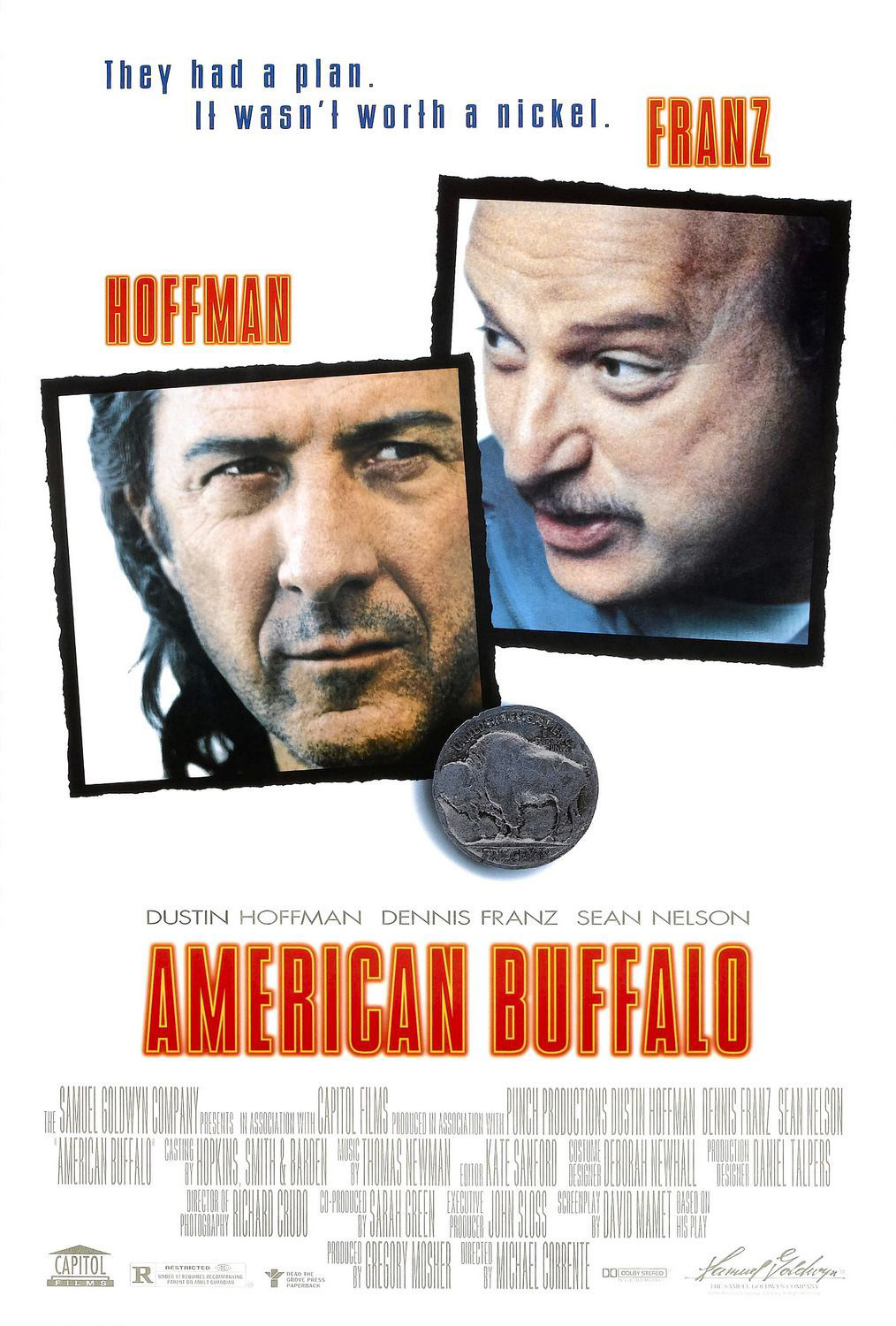

The core of “American Buffalo,” and all of Mamet’s plays, is in the vernacular of the characters. They have a way of implying just what they’re thinking, in ways they do not intend. “If I could come up with some of that stuff you were interested in,” Teach asks Don, “would you be interested in it?” And “the only way to teach these people is to kill them.” And when a gun is introduced into the plot: “God forbid something inevitable occurs.” The shop is a shadowy space filled with objects we cannot imagine much demand for. Don (Dennis Franz) has made it into a sort of warren for himself, and in this film version by Michael Corrente there are alcoves and mezzanines receding into the shadows–caves of tarnished treasure. We gather Don supports himself in ways other than by selling these things. Teach (Dustin Hoffman) hangs out in the store, and the two of them engage in an endless, desultory conversation–talk filled with possibilities, eventualities, potentialities, hypotheses and folk wisdom. Bobby (Sean Nelson, from “Fresh”), the black kid who works for Don, imperfectly understands the occupation of his employer, but guesses some and wants to know more.

The action in the play involves the possible theft of a coin collection. A man named Fletch may assist them in the crime. Much is made of Fletch: He looms importantly in their regard. When Fletch doesn’t turn up as scheduled, various fallback options are explored. “What a day,” Don and Teach agree, again and again, as if the day had created them instead of them creating the day.

It is a cliche, but true, that some plays have their real life on the stage. “American Buffalo” is a play like that–or, at least, it is not a play that finds its life in this movie. I’ve seen the play more than once, most memorably in London with Al Pacino and J.J. Johnston, and have never grown tired of it; the language contains such rich humor just beneath the surface. It’s not a comedy (although sometimes we laugh), but an elaborate playwright’s joke. Mamet, like one of his characters, invents a labyrinthine, convoluted spiel leading nowhere, and like a magician distracts us with his words while elaborately not producing a rabbit from his hat. The insight, I believe, is that these characters do this every day: Uneasily perched in the darkness of the store, uncomfortable with the light and normality outside, they make plans, and plans, and plans.

On the stage, they are trapped in their space and time. In this film (although the action has been opened up only minimally), they seem less confined. Crucially, they also seem to think their plans are more urgent. Dustin Hoffman somehow seems to be trying too hard, to be making too much of an effort to think his thoughts and speak them. His Teach doesn’t seem in on the joke, which is that nothing much is going to happen and Teach sort of knows that.

One doesn’t want to see a knowing wink from Teach; it would be wrong for him to tip his hand, to let us see he knows this is dialogue and performance and no payoff. But the wink should be underneath somewhere. At some fundamental level the performance should let us know that Teach has been down this road before–that the road is all there is for Teach. Pacino was able to convey that, but Hoffman has a slight but crucial excess of sincerity.

Dennis Franz, as Don, successfully conveys the notion that he does not much care one way or the other. He exudes a proprietorship over the store and the action: This is his space and he waits here, indefinitely, it would seem, while his friends visit him in order to be seen leading their lives. His function is to witness them: Teach exists because Don owns a store and sits in it and provides a foil and an audience. Bobby is not such an important character, but Sean Nelson, who was so powerful as a child actor in “Fresh,” shows here just the right tone: Bobby is not in on the joke, does not know these rituals have been repeated from time immemorial, and thinks Don and Teach are substantial beings.

Because the film never really brings to life its inner secrets, it seems leisurely, and toward the end, it seems long. It doesn’t have the energy or the danger of James Foley’s film version of Mamet’s “Glengarry Glen Ross.” The language is all there, and it is a joy, but the irony is missing. Or, more precisely, the irony about the irony.