Steve James’ “America to Me” is a momentous achievement, both a statement on where we are right now in terms of race and how we need to work together to get somewhere better. As he has with films like “Hoop Dreams,” “Life Itself,” and “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail,” James and his team find a way to place their empathetic, individual stories against a larger backdrop of social issues across the country. James is one of our most humanist filmmakers—someone who not only knows how to draw out the most interesting aspects of his subjects’ lives but seems to honestly care about who they are and where they’re going. He’s a cinematic listener, someone who gets comfortable enough with his subjects that he allows their best selves to come out on-screen, and allows us the optimism to think that there are people like the kids and teachers in “America to Me” all around this country—people just trying to get through the day, have their voices heard, and maybe make a difference.

The concept of this ten-episode series, premiering on Starz Sunday night, is simple but brilliant. James and his crew spent a year at Oak Park and River Forest High School, on the west side of Chicago (and only about an hour from yours truly). OPRF is a fascinating school to study because it draws from several racial and economic backgrounds. With 3,200 kids, it’s a place where it seems like anybody can find success, or just as likely get drowned out by it all. How do you find your own personal space in such a large crowd? And how is that teenage quest for identity that happens during high school shaped by racial politics?

“America to Me” is unafraid to address that last question directly. It is a project that was pitched to the school as “stories of race and academics in this diverse public school,” and it is constantly circling back to issues of diversity. It can be large picture conversations about how the achievement gap between minority and white kids has actually been growing over the last few years or small picture ones about individual stories from the show’s subjects. There are fascinating talking points in between those two extremes as well, especially in how teachers at different levels and from different backgrounds handle race. Many of the teachers in “America to Me” seem willing to admit that they don’t have all the answers. How do you get kids in an AP class that’s mostly white to talk about race in a way that’s productive when it comes time to study The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass? They’ll all join in the chorus that slavery is bad, but shut up when you mention white privilege.

High school is really when so many of us define who we are—how could teachers ignore the racial aspect of that? You really get to see how hard some of these people are working, asking questions of themselves, and trying to make a difference with their students. There’s a moment later in the season when a teacher can see the impact she had on a formerly-quiet student speaking up for himself that’s so subtly moving that it brought me to tears. It’s an event that is obviously minor in the grand scheme of things, but just encouraging young people, especially young black people, to express themselves can be so major in that young person’s life. So much of “America to Me” is just about providing spaces for people to be themselves, something that’s simply harder for non-white kids than it should be. As one of the most memorable students says, “This school was made for white people.”

The gift of “America to Me” is that the big picture for all of us is in the relatively little one of this particular school; the macro is in the micro. Anyone could simply film the action of a year at an American high school, especially in a racially diverse neighborhood, and produce something interesting about where we are in the ‘10s, but it’s the way that James and his team construct “America to Me” that’s so remarkable. You can feel both empathy and frustration in the same moment. People are trying so hard, but why is the gap growing? Part of the problem can be reflected in a question from episode six that I kept reflecting on: “How do we define smart?” It may be different from you to me, or for kids from different backgrounds.

Throughout the series, I kept thinking about an early scene in which the achievement gap is discussed and a parent speaks up, reminding everyone in power not to lose sight of her kid while they’re changing policies and looking to the future. While people have the best of intentions when it comes to the bigger issues of OPRF, kids are going about their lives, thriving and failing. The question at the heart of OPRF and the series is one that’s essential for all of us, especially those of us with kids: How do we fix the bigger picture of society’s problems without losing track of the day-to-day ones? And it’s a question that can be applied on a grand scale. As the conversation about the changes this country needs intensifies, how do we not lose sight of the actual people impacted by its inequity?

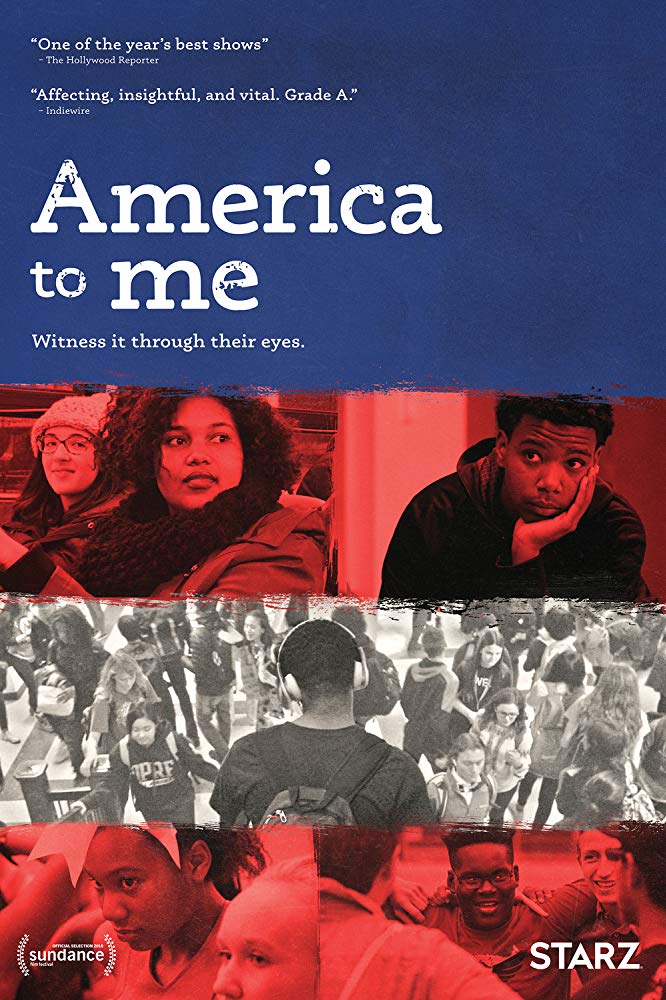

To amplify his themes, James and his team chose a fascinating array of teenagers, many of whom seem to be pouring everything they have into their passions. We spend a lot of time at spoken word, wrestling, and cheerleading competitions. Again, James allows themes to emerge through action and not just through interview. It’s about perception that black girls dancing on off time at a cheerleading competition will be perceived differently than the white ones, or how spoken word from a white person is going to inherently be less embraced by the judges than the black ones speaking to issues of Chicago racial injustice. James and his team go into these racially charged areas like athletics and poetry, but then reveal how much the obvious racial politics on display there are also a part of everyday life. And yet you should know that “America to Me” is not a mournful cry for racial justice. It is often joyful. When I think of it, I think of the smiling faces of Charles, Kendale, Grant, Tiara, and the rest of the kids at OPRF. They’re just trying to get through the complex, challenging days of youth. They’re just trying to find their own definition of America. What can we, and I mean all of us, do to help them? It starts with listening to their stories.