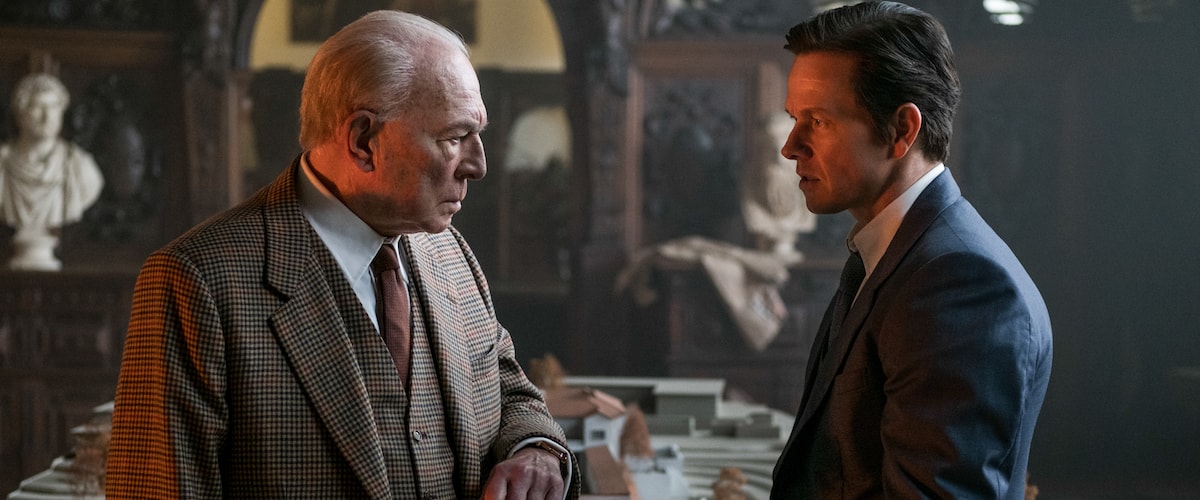

Ridley Scott’s “All the Money in the World” is a long-winded but engrossing kidnap thriller. The heart of the film is a trio of lead performances: Michelle Williams as Gail Harris, the mother of an abducted heir to the Getty fortune; Charlie Plummer as the heir, John Paul Getty III; and Christopher Plummer as the young man’s grandfather, John Paul Getty, the richest man in the world at the time of the kidnapping. (The two Plummers are not related, incredibly.)

“All the Money in the World” is brutal and funny in the darkest way. The dark humor comes from John Paul Getty’s attitude toward his fortune. He’s so miserly he makes Ebenezer Scrooge look generous. Naturally, he’s the real target here; he would have to be, considering Gail is just another middle class single woman who barely has two nickels to rub together, thanks to her decision to decline Getty family funds in exchange for keeping custody of her kids after divorcing the old man’s drug addicted son. “All the Money in the World” would be ten minutes long if grandpa would just pay what the criminals are asking for the release of his grandson—$17 million—instead of hemming and hawing and trying to get the price down.

Grandpa has reasons for haggling—not good ones, but reasons. Ultimately, though, he just seems like he’s not wired right. His grandson’s opening narration suggests that rich people aren’t actually like you and me—that money has deformed their minds—but the elder Getty’s behavior is so repugnant on so many levels, and so profoundly dislocated from anything resembling empathy, that money alone doesn’t strike me as the best explanation for his actions. I don’t know if this is an unresolved complication, a basic failing of the screenplay, or a dimension that Scott and/or Plummer added to the role during shooting.

If the latter, however, what’s onscreen is more interesting than the younger Getty’s diagnosis, because it means we’re watching an emotionally stunted and perhaps mentally ill person with access to billions allow a blood relative to suffer just so that he can save a few bucks. In other words, it’s not the money, it’s him. To most of us, the stated ransom is an unimaginably huge amount, but to somebody like Getty, it’s the equivalent of the coins hidden under sofa cushions. We’d do whatever it took to save a loved one in similar circumstances, but John Paul the First has such an oversized dealmaker’s ego that he won’t take out his checkbook unless the terms are just right.

Gail’s tactical restraint when confronted with her former father-in-law’s iciness is commendable, and Williams plays it just right, letting us see Gail’s anger and frustration while making us believe that she could tamp it down out of sight when dealing with the elder Getty and his associates. What astonishing discipline this woman had! The old cheapskate acts as if this is all just a large-scale version of saving eight bucks buying a statue at a flea market. John Paul III could be murdered or tortured as a result of the stubbornness of an old man who prides himself on never meeting the first offer, and trying to save money on everything, even a transaction as basic as sending out laundry while staying in a five-star hotel (he washes and dries his own sheets to shave a few bucks off his tab).

Scott is relatively restrained here, letting his stars carry the day and declining to unleash the full force of his directorial power except in a handful of intricate setpieces (I won’t specify which ones here, because I doubt anyone but students of the Getty family history know all the details, and a couple of them are genuinely surprising). A certain monotony sets in during the middle section, which replays too many similar beats too close together—if the script were looking to combine or cut incidents, this would’ve been the place to do it—but on the whole this is a more-than-solid effort.

It’s also a throwback of sorts. Adapted by screenwriter David Scarpa from John Pearson’s 1995 book Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty, it has a welcome 1970s flavor, by which I mean that it’s about recognizable human beings dealing with tense situations that feel real because they happened. The story is told in classically shaped scenes with beginnings, middles and ends, and shot mostly in real locations. The wide-format cinematography creates tension by shoving characters off to one side or boxing them inside doorways or windows and letting you wonder what unseen threats might be lurking in the rest of the frame.

As is often the case in his non-science fiction movies, Scott splits the difference between overwhelming, almost tactile-seeming realness, and pure, uncut Hollywood fantasy, and you just have to roll with it. There’s a standard disclaimer at the end of the film, stating that certain liberties were taken with the historical record. I’d imagine that a lot of them had to do with placing Gail and her partner in misery, Getty’s business manager and former CIA operative Fletcher Chase (Mark Wahlberg, who isn’t terrible but does not radiate intelligence and ultimately makes no particular impression). The movie often puts the duo at the sites of dangerous activities that they probably didn’t get anywhere near in real life.

The film is a testament to the awesome work ethic of its 80-year old but still apparently tireless director, who fired Kevin Spacey, the actor who had originally played Getty, a month before the scheduled release date, after Spacey was accused of multiple accounts of sexual misconduct, deleted all of his footage, reshot the affected scenes with Plummer in the role and dropped them into the finished movie. This is not the best place to get into the particulars of the production—they’ll be nothing more than a footnote or asterisk in a couple of decades anyway—but they’re worth noting because the end product is much better than anyone could have expected, considering the challenges faced and met by all involved.

In fact I wouldn’t be surprised if Plummer got another Oscar for this part. If he does, it shouldn’t be seen merely as an acknowledgment of good work under weird and unfortunate circumstances, but as recognition of how precise and fearless he is. There is nothing likable about the elder Getty, indeed very little that’s recognizable as anything but evidence of profound, maddening dysfunction. Plummer embodies the character so completely that his Getty transcends the movie he’s in, and starts to seem emblematic of the times in which the film was released, an era when money seems to matter more than mercy.