To outsiders, Alice Ferrand (Emilie Piponnier) looks like she has it all. She has an adorably playful toddler named Jules (Jules Milo Levy Mackerras); a doting partner, François (Martin Swabey), who showers her with affection; a posh apartment she helped pay for; a job and friends. But that domestic dream turns into the darkest of nightmares when François disappears without a trace and Alice discovers that not only has he strayed from their relationship by seeking the company of high-priced escorts for some time but also that he’s used her money and stopped paying off their home to do so. On a whim, Alice decides to find out more about the world of well-paid escorts and incidentally finds the way to save her and Jules from almost certain eviction.

Writer and director Josephine Mackerras mixes the martial drama with a message about double standards and stigma. Alice’s prejudices against escorts do not last long after she meets Lisa (Chloé Boreham), a fellow sex worker who coaches her through her first calls, best safety practices and tips for navigating the system to continue getting work. Some of the best parts of the movie blossom out of the pair’s newfound friendship. Unfortunately, Alice’s problems are not entirely resolved by her new job. Her new profession could also cost her custody of her son, exposing both the legal and cultural double standards against women sex works and the ease with which men who pay for sex can dodge similar consequences.

“Alice” also makes a point to show how society can abandon women and single moms, leaving them in vulnerable situations like Alice’s. When she calls her mother, Alice finds no support, the previous generation instead scolds her for not meeting her husband’s needs and for giving up on her marriage so easily. Their phone conversation is a relatively quiet scene, but immensely crushing. It’s only the first of many times Alice finds herself on her own. Later, in the scramble for a late-night call, she frantically tries to get Jules to a friend’s house but her friend rejects her when she sees Alice in full makeup and a cute dress. The moment leaves Alice to choose between her baby’s safety or their potential well-being. There are few resources for her to turn to in her new life beyond Lisa.

As Alice, Piponnier is phenomenal, putting in a meticulously reserved performance in what could very well have been a melodramatic role. She’s almost soft-spoken at the beginning, talking gently to both her son and partner with tender cadence. When her fortunes change, the change is subtle, her cool-headed exterior crumbling bit-by-bit. There are a few small meltdowns and crying spells but most of her energy is spent pulling herself together and steeling her resolve for whatever challenge lies ahead.

Mackerras also shows a fair amount of restraint in her direction, choosing to focus closely on Piponnier’s face and body language. There’s so much said in Alice’s slouched shoulders, exasperated sighs and deer-in-the-headlights stares when she awkwardly meets her first clients, and none of it is lost in the heat of the moment. It also speaks to the low budget resourcefulness of Mackerras, who used her own apartment for the one in the film and cast her son in the role of Alice’s child. But outside the day-to-day grind of work and shuffling between her nice home and even fancier hotels, Alice spends some of her rare in-between time on the street, having fun with her son Jules or catching up with Lisa. Through the work of cinematographer Mickaël Delahaie, Alice lives the life of an everyday Parisian, living mostly away from the tourist hubs but still within the city’s beauty. Even in some of Alice’s most desperate moments, things never seem dramatically dark or empty. The city moves on around her, the lights and sounds uninterrupted, unaware of her internal heartbreak.

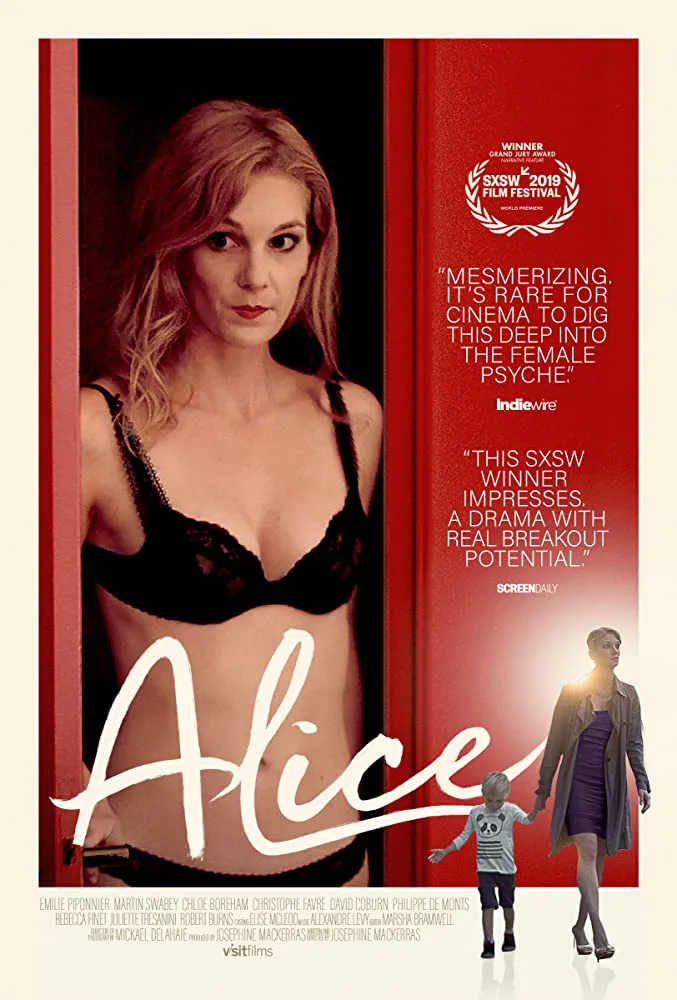

“Alice,” winner of last year’s South by Southwest Grand Jury Prize, drives home its message a touch too heavy near the end, emphasizing its point on the double standard against women in sex work at the expense of well-tuned drama before it. There’s some uncomfortable—but realistic—arm twisting to prove its point, but when the credits roll, there’s a well-earned sigh of relief. Despite those bumps, Piponnier’s performance and Mackerras’s empathetic vision are still very rewarding. The movie avoids casting a judgmental light on escorts and instead allows its main character to use it as a way to find herself and her independence, a sign that the conversations around and depictions of sex work in media are hopefully evolving towards better, nuanced stories—at least in France.

Available on Virtual Cinema today, 5/15.