It’s a basic movie situation. Desperate criminals are trapped and surrounded. They have hostages. The hard-boiled cop in charge issues an ultimatum. During a long and exhausting night, the tension builds while the men consider their options. And the hostages try to reason them out of a dangerous decision. In the old days it was always Pat O’Brien as the good Irish cop, a bullhorn to his mouth, shouting out a final ultimatum.

Why did the actor Kevin Spacey choose this formula for “Albino Alligator,” his first film as a director? Maybe because it’s fun for the actors, who are required to move through plateaus of emotions. Maybe because by limiting the action mostly to one room, it eliminates distractions and allows for a closer focus. Maybe because he liked the screenplay by Christian Forte–even though it violates that old writer’s rule: `Never quote your title in the dialogue.’ Spacey does what can be done with the material, but it never achieves takeoff velocity. The heart of the problem, I think, is our suspicion that in real life these situations don’t turn into long discussions. The crooks are likely to be too scared, too inarticulate or too confused for the kind of verbal jockeying that occupies most of “Albino Alligator.” The enterprise seems contrived–more like an actors’ workshop than a drama.

The story takes place in New Orleans, where we see a group of law enforcers on a stakeout. Three robbers–not the ones the feds are looking for–botch a job at a warehouse and try to make a quick getaway. They have the bad luck to run directly into the federal roadblock, and a cop is killed (there’s a nice shot here of a book of matches; he needed a light at just the wrong time).

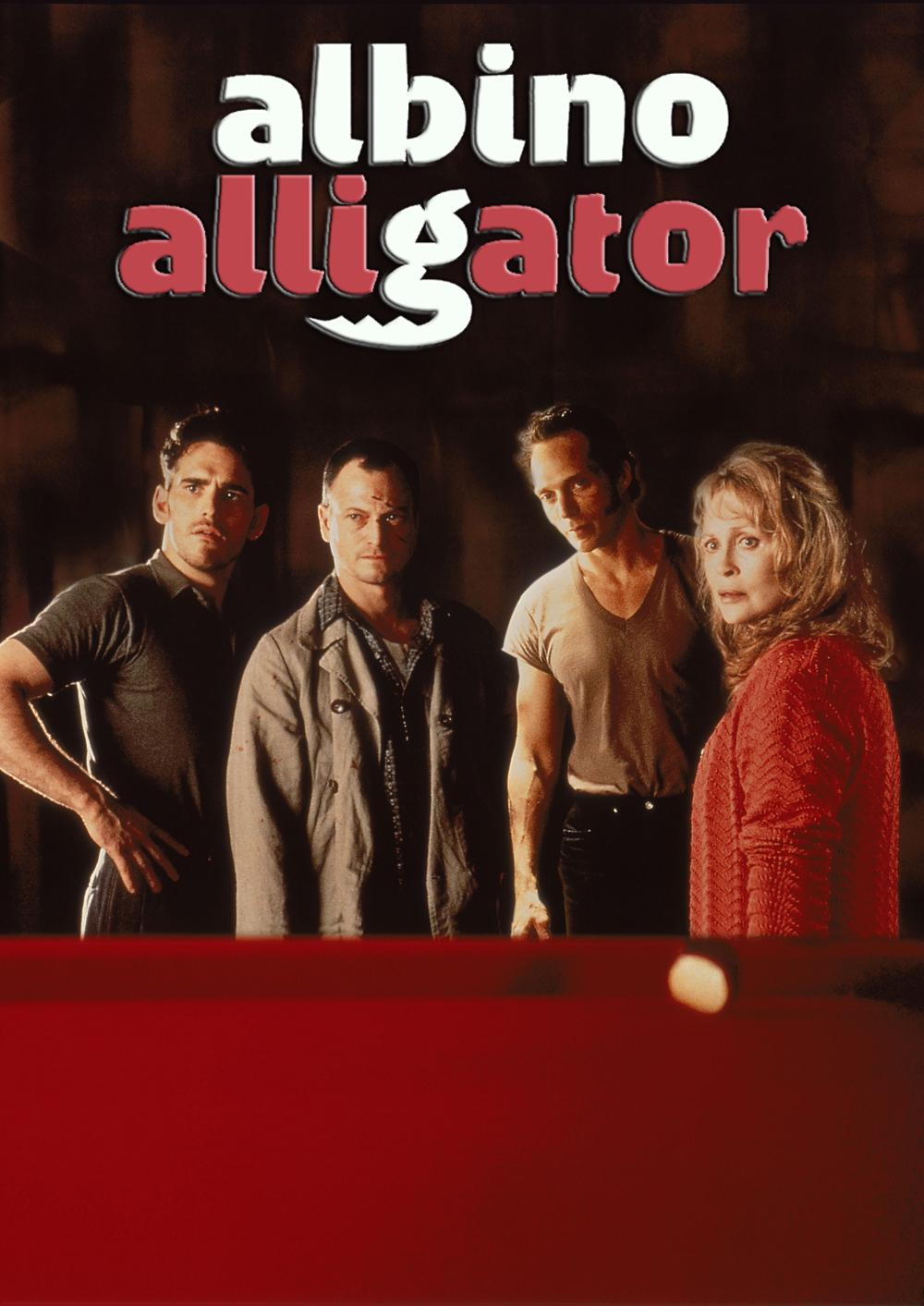

In the car are Law (William Fichtner), who is a cold psychopath; Milo (Gary Sinise), who seems more like your high school civics teacher than a criminal, and Dova (Matt Dillon), who is the leader of the gang but not necessarily in control. Two agents are killed when the chase goes wrong, and Milo is injured; the three stumble into an all-night dive poetically named Dino’s Last Chance.

Dino is the owner, a phlegmatic old-timer played by M. Emmet Walsh. His bartender is Janet (Faye Dunaway). There are three customers in the bar: A kid playing pool (Skeet Ulrich), a guy in a suit who looks out of place (Viggo Mortensen), and a barfly (John Spencer). They all seem too sober to be drinking at 4 a.m., but if they were like most all-night drinkers, it would take Eugene O'Neill or Charles Bukowski to tell their story.

Dino’s is quickly surrounded by law-enforcement officers, led by Browning (Joe Mantegna), who barks the usual orders and issues the usual ultimatums. There’s no possible escape; the bar, which is below street level, has no back door and no windows. The criminals are doomed to be caught or killed, unless they come up with a bright idea. They do, sort of.

I will not be giving away plot secrets if I describe at this point the albino alligator connection. According to an anecdote told in the movie, alligators force an albino to go out first, in order to flush out the opposition, after which they pounce from ambush. It’s ingenious the way Forte’s screenplay employs this principle, and interesting the way he develops the characters. Walsh and Dunaway try to reason with the desperados, and the customers (who are not all exactly who they seem) have a turn. There’s a dynamic within the gang involving Sinise, who begins to think of his Catholic upbringing; Fichtner, who wants to blast everyone away, and Dillon, who tries to keep a level head.

It is all done about as well as it can be done, I suppose. Hostage movies follow such ancient patterns that it’s rare to be surprised by one, and this one does have some surprises, not very rewarding. Occasionally the genre will be transformed by brilliant filmmaking, as it was in “Dog Day Afternoon.” Not this time.