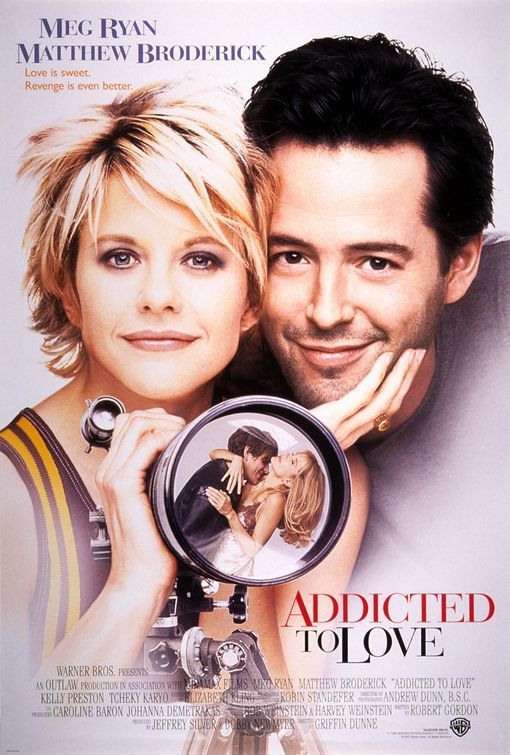

I have to train myself to stop expecting plausibility in films. After all, I’m the guy who argues that nothing is implausible in a film if it works, since it’s all part of getting the job done. And yet in the opening scene of “Addicted to Love” I was struggling. Astronomers have a telescope trained on a supernova. Then suddenly it’s noon and the chief astronomer (Matthew Broderick) lowers the telescope until he can focus on the woman he loves (Kelly Preston) frolicking in a meadow with the students she teaches.

Huh? I’m thinking. They can see the stars through that telescope at high noon? I should have taken the clue right there. Then I wouldn’t have been distracted a little later, when Preston announces she wants to leave their small town and spend some time in New York City, and as her commuter plane taxis to take off, Broderick races beside it down the runway in his pickup truck, waving goodbye. I think that’s against FAA regulations.

So look. I’m not being fair to the movie. It’s obviously a romantic fantasy, and only a curmudgeon would nitpick. What bothered me more was that the characters are supposed to be intelligent, and yet they have the maturity of gnats. It is always a problem in a love story when the rival seems more interesting than the hero, and that’s what happens here.

But let’s back up. Broderick plays Sam, the astronomer, who follows his lifelong love Linda (Preston) to the big city, where she has gone because she finds small-town life stagnating. Sam tracks her down by canvassing residential hotels until he finds the right one (don’t try this yourself unless you have lots of time). Then he discovers that Linda is dating a French chef named Anton (Tcheky Karyo). In fact, she’s moving in with him.

Sam sneaks into an empty building across the way and, using his astronomer’s knowledge of lenses, builds a refracting gadget that projects an image of their apartment onto a wall in his (the technical term for his device is “camera obscura”). Later he bugs their place, so he can relax on his sofa and watch a moving picture of their private life, with sound. Using his scientist’s training, he graphs their progress (there is even a chart showing her daily smile quotient) to predict when they will break up.

During this process, a mystery figure on a motorcycle turns up. It is an old rule in movie comedies that whenever a motorcyclist’s head and face are completely obscured by a helmet, that motorcyclist is inevitably revealed to be a woman. True again this time: It’s Maggie (Meg Ryan), who is the jilted lover of the French chef. Since Maggie and Sam have their losses in common, they team up to try to sabotage the two happy lovers across the way.

Among their tricks: They pull a pickpocket scheme to get lipstick on his collar. They bribe kids to use squirt guns to douse him with perfume. These clues are supposed to make Linda jealous. By this point in the film, I was squirming: At what intelligence level is the story pitched? Sam eventually inveigles himself into the kitchen of Anton’s restaurant, as a dishwasher, so that he can masochistically observe his rival at close quarters. This leads to a conversation between the two men in which Anton seems so manifestly wiser and more grown up that I was reminded of a generalization I once heard: “European films are about grownups, and American films are about adolescents.” Not true in all cases, of course, but it’s dramatically true here that Anton has an adult’s understanding of the world, and the Sam character thinks he’s living in a sitcom.

How much more interesting this situation might have been if they’d forgotten about the reflecting lenses and the practical jokes and tried to devise a comedy based on personalities and dialogue! That might even have led to an unexpected outcome. Instead, we get a plot so predictable that there cannot be a single person in the audience who doesn’t know Broderick and Ryan are destined to fall in love with each other. Not simply destined, but absolutely required to, by the bylaws of the Hollywood Code of Cliches.

The actors are very engaging. The production design (including the reflecting lenses) is artful and ingenious. The direction, by Griffin Dunne, is smooth and confident for a first-timer. There are nice supporting roles for Maureen Stapleton, as a wise grandmother, and (Nesbitt Blaisdell) as Linda’s father, Mr. Green, who assigns himself to read her Dear John letters. There is, in fact, a lot of good stuff here, but it’s all at the service of an imbecilic approach. It’s like bright people got together to make the film and didn’t trust the audience to keep up with them.