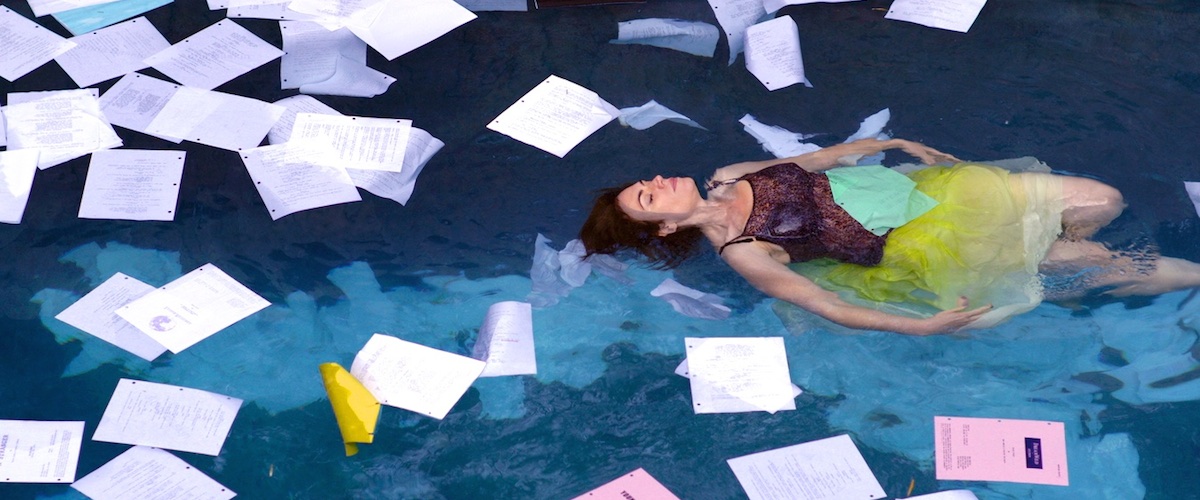

The dilemma of the present-day female actor is the subject of this first fictional feature written and directed by media artist Elisabeth Subrin. Maggie Siff, whose smart intensity as a performer practically guarantees an interesting characterization, here plays Anna, a successful television actor whose incipient burnout finds her strewing scripts across her swimming pool and floating among the pages. She’s also negotiating a Ritalin addiction and treating an auto-immune illness.

When her concerned agent insists that Anna “take a real break,” Anna does something relatively radical: She bounces back to her New York roots, and parachutes into the lives of the friends and lovers from her days as a “scrappy” theater struggler. “It seems like you’ve got some unfinished business,” observes the rando beardo she makes the mistake of sleeping with a little more than halfway through the movie. Her old buddies Kate (Cara Seymour) and Isaac (John Ortiz) are still struggling, or in Kate’s case, not: she says she’s given up acting. Anna, on the other hand, thinks she’s not an actor anymore. Isaac, still a committed boho dude whose marital arguments actually contain words like “authenticity,” is about to unveil a script about a group of friends in 1990s New York theatre, one of whom goes on to become a famed and well-compensated star. Anna’s discovery of this script leads to a mini-meltdown. Isaac then ups whatever ante he’s putting down by asking Anna to participate in a reading of the script.

One of the points of this multi-character study seems to be that in a life in the arts, unfinished business is the only kind. As far apart as Anna’s circumstances have taken her from Kate and Isaac, she falls back into whatever dance they were doing decades before without missing a step, in spite of the pain and confusion it brings her. Side notes from the director—shots of construction sites in the New York neighborhood where the characters have at least tried to settle (an eviction is a turning point in the story line)—underscore that the social concerns of some of the characters are also hers. In Subrin’s ultimate vision, the most dire catastrophe is monetary success.

“I know who you are,” one character says to Anna, who’s withheld her identity from him. Anna’s problem is that she’s no longer sure herself, and her return to her roots does not bring about the trite kind of self-discovery or rediscovery that a more conventional film on this subject would serve up. Subrin’s visual style is similarly offbeat. While she uses a handheld camera with the same frequency most indie directors do, she tends to keep her characters in a middle distance (close-ups are rare, and as a result they register more strongly) and she keeps her color palette consistently cool. It’s a way of bringing some space, a useful detachment, to bear on subjects that are plainly very important to her. The discipline pays off; “A Woman, a Part” mixes passion and ambivalence to create a work with ambiguities that seem earned, and lived in.