In the horror of trench warfare during World War I, with French and Germans dug in across from each during endless muddy, cold, wet, bloody months, not a few put their rifles into their mouths and sent themselves on permanent leave.

Others, more optimistic, wounded themselves to get a pass to a field hospital, but if this treachery was suspected, the sentence was death. “A Very Long Engagement” opens by introducing us to five French soldiers convicted of wounding themselves; one is innocent, but all are condemned, and it is a form of cruelty, perhaps, that instead of being lined up and shot they are sent out into No Man’s Land and certain death.

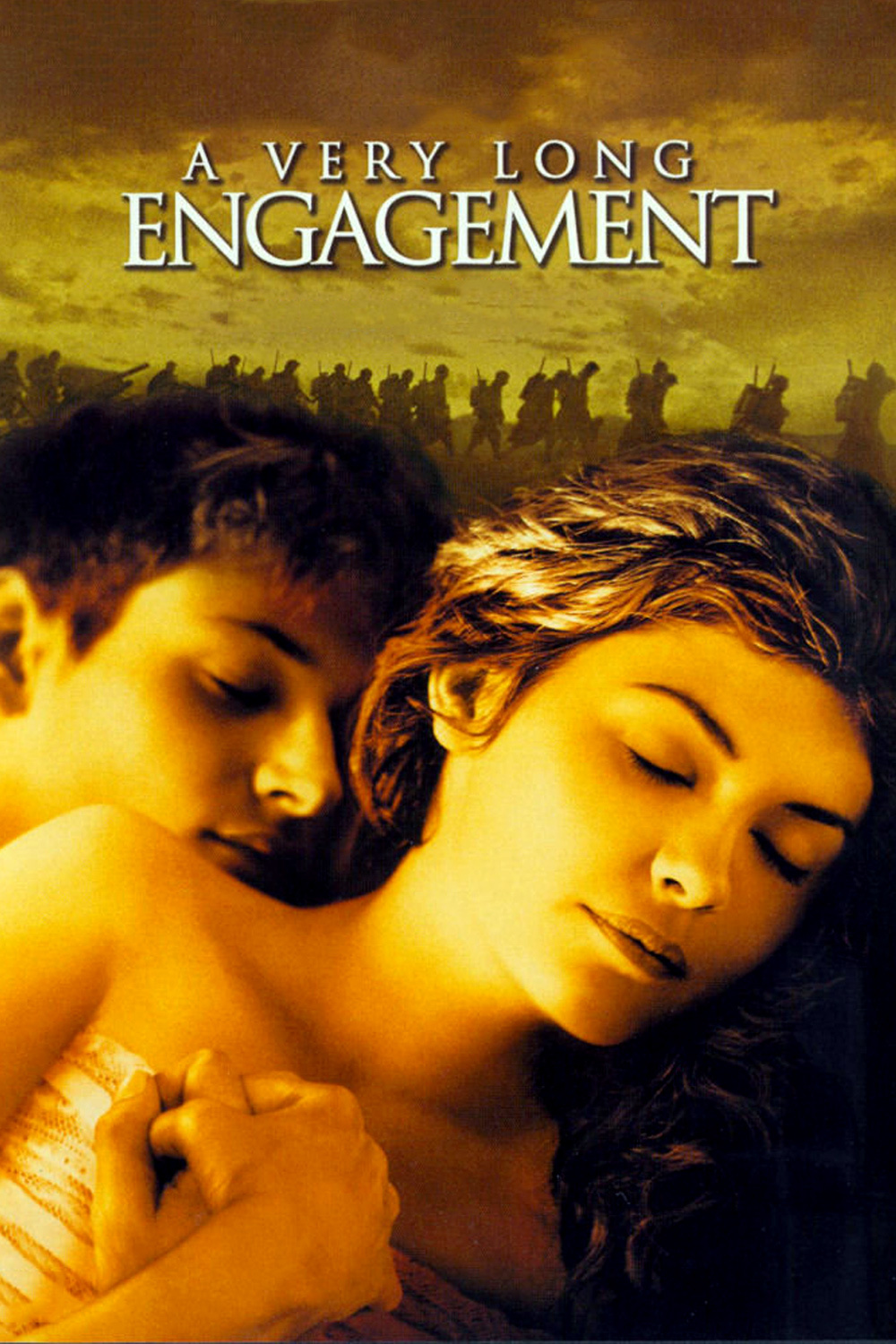

The movie is seen largely through the eyes of Mathilde (Audrey Tautou), an orphan with a polio limp, who senses in her soul that her man is not dead. He is Manech (Gaspard Ulliel), son of a lighthouse tender, a boy so open-faced and fresh he is known to all as Cornflower. After the war, Mathilde comes upon a letter that seems to hint that not all five died on the battlefield, and she begins the long task of tracking down eyewitnesses and survivors to find the Manech she is sure is still alive and needs her help.

This story is told in a film so visually delightful that only the horrors of war keep it from floating up on clouds of joy. Having not connected with his earlier films “Delicatessen” and “The City of Lost Children,” I was enchanted, as everyone was, by Jeunet’s first film with Audrey Tautou, “Amelie.” Now he brings everything together — his joyously poetic style, the lovable Tautou, a good story worth the telling — into a film that is a series of pleasures stumbling over one another in their haste to delight us. I will have to go back again to those early films; maybe I am learning the language.

That is not to say “A Very Long Engagement” is mindless jollity. From Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves and from a hundred films like “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “Paths of Glory” and “King and Country,” we have an idea of the trench warfare that makes WWI seem like the worst kind of hell politicians and generals ever devised for their men. To be assigned to the front was essentially a sentence of death, but not quick death, more often death after a long season of cold, hunger, illness, shell-shock and the sheer horror of what you had to look at and think about. Jeunet depicts this reality as well as I have ever seen it shown on the screen, beginning with his opening shot of a severed arm hanging, Christ-like, from a shattered cross.

Against these fragments he buttresses his fancies, his camera swooping like a glad bird over Paris and the countryside, his narrator telling us of Mathilde and her quest. These moments have some of the charm of the early scenes in Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim,” before the same war destroyed their happiness.

Mathilde enlists a dogged old bird of a private detective (Ticky Holgado, who you may remember from the cover of Amelie’s talking book). He plods about quizzing possible witnesses with the raised eyebrows of an Inspector Maigret and gradually a scenario seems to form in which Manech is not necessarily dead.

As a counterpoint to Mathilde’s hopeful search, Jeunet supplies another search among the same human remains, this one carried out by a prostitute named Tina (Marion Cotillard), who figures out who was responsible for the death of her lover. Her means of revenge are so unspeakably ingenious that Edgar Allan Poe would twitch in envy.

The barbarity of war and the implacable logic of revenge are softened by the voluptuous beauty of Jeunet’s visuals and the magic of his storytelling. Here is a director who loves — adores! — telling stories, so that we sense his voluptuous pleasure in his own tales. He must work in a kind of holy trance, falling to his knees at night to give thanks that modern special effects have made his visions possible. Some directors abuse effects. He flies on their wings.

Whether Mathilde finds Manech is a question I should not answer, but reader, what do you think is the likelihood that an angel-faced girl with polio could spend an entire movie searching for her true love and not find him? Audiences would rip up their seats. The point is not whether she finds him, but how. Can Jeunet devise their reunion in a way that is not an anticlimax after such a glorious search? What can they do, Mathilde and Manech, and what can they say? Reader, the film’s closing moments are so sad and happy that we know, yes, it has to end on just that perfect note, held and held and held.