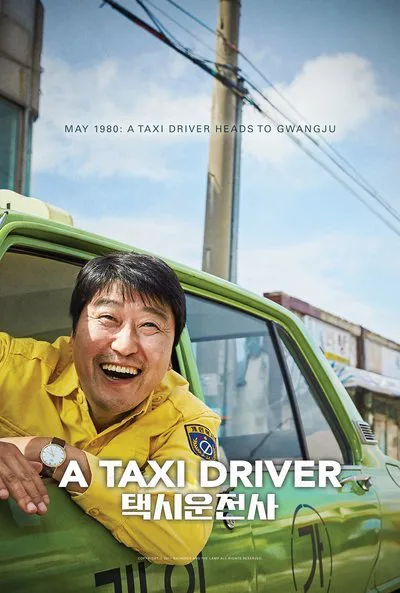

If nothing else, the South Korean historical drama “A Taxi Driver” proves that seemingly unstoppable star Kang-ho Song can, in fact, do wrong. Song, perhaps best known to American audiences for “The Host” and “Snowpiercer,” has an emotional range that very few contemporary leading men have. He proves his versatility once again in “A Taxi Driver,” a tribute to real-life German journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter (Thomas Kretschmann) and the mysterious Korean cab driver (Song) that accompanied Jürgen to and from rural Gwangju during the violently suppressed student protests of 1980. Song is so charming that he makes you want to care even when his character is defined by unmoving declamations and a predictable character arc. Song’s performance makes me wish the rest of “A Taxi Driver” was as thoughtful.

Song plays Sa-bok Kim, a penny-pinching widower and the oblivious father of pre-teen Eun-sung (Eun-mi Yoo). Sa-bok’s story is, as realized in the film, fairly trite. He learns to become a better, more politically conscious man after he chauffeurs Jürgen—referred to as “Peter” throughout the movie—past military barricades and into Gwangju. Unfortunately, Sa-bok, a character who is most human when he is most neurotic, eventually becomes completely unsympathetic once he stops being selfish, and starts acting like a man on the road to an unbelievable moral awakening.

Screenwriter Yu-na Eom and director Hun Jang (“Rough Cut,” “Secret Reunion”) both focus primarily on Sa-bok’s transformation into a political figurehead. This myopic interest in Sa-bok as a zero-to-hero success story is instantly frustrating since it means that Peter is left largely undeveloped. All we know about him is that he saw that a news story needed reporting, then traveled from Tokyo to Seoul to Gwangju, and finally reported the news because he wanted to shed light on the situation.

This uncritical deference is almost certainly an ingrained peril of working with the real life Linzpeter shortly before his death. Still, there’s nothing more frustrating than watching Peter portrayed as a starch-stiff supporting character whose very presence is supposed to awaken noble aspirations in a lead character. Peter’s essentially a sandwich board-sized blank slate that Eom and Jang plaster with unbelievable rationalizing like “I’m a reporter. Reporters go wherever there is news,” and “Once this footage airs, the entire world will be watching. You’re not alone.” As a result, there’s never a moment where Peter’s motives are small enough to be sensible.

The same is thankfully not true of Sa-bok. At first, he’s a deadbeat dad who cares more for his taxi cab’s broken rear-view mirror than he does about his fellow man. He’s four months behind in rent, and everything in his life depresses him, including Eun-sung, and his sympathetic landlord’s nosy wife. As is often the case in Korean melodramas, the sins of the father are passed on to their children. So Eun-sung ignores her father’s warnings, and chooses to protect her dad’s low reputation from the schoolyard insults of the landlady’s snotty son. But Sa-bok doesn’t go easier on her as a result. Instead, he callously scolds Eun-sung: “Learn to bear it. Life is never going to be fair.”

But soon enough, Eun-sung stops being important beyond her significance as an emotional pressure point that Peter and his super-humanitarian mission actively lean on. In order to get back to his daughter, Sa-bok must help Peter get the incriminating footage he needs. Never mind that Peter deliberately singles out a student protester with a head wound just because the kid’s injury makes for good optics for Peter’s story. Peter’s a good guy, so the ends implicitly justify the means.

That assumption does not, unfortunately, enliven shrill, but emotionally flat scenes where Sa-bok wonders aloud things like “Why were those soldiers acting that way” and “How can they just shoot people?” Every crucial emotional moment feels too neat, and schematic, even immediately involving chase scenes—ones where government-hired gangsters attempt to flush Peter and Sa-bok out of hiding by threatening student protesters. Never mind that the film’s events really happened: no amount of thespian magic can enliven the crucial, unimaginatively realized scene that revolves around Sa-bok’s lame declaration of loyalty to Peter: “I left a passenger behind. Someone who really needs to take my taxi.”

Song tries valiantly to breathe life into his stillborn character, and he often succeeds when Sa-bok is a boorish clod. He’s especially funny when he impatiently barks “Where is the road” to a reluctant Gwangju resident who benignly tries to warn Sa-bok and Peter away from their destination. Song is even good enough to make the otherwise canned scene where he tearfully breaks down, and talks about how hard it was to lose his wife. As he sobs uncontrollably, Song makes you wish that this moment had as much impact as it should. This big moment ultimately falls flat though, as the makers of “A Taxi Driver” would sooner print an unbelievable legend than a relatable truth.