Even before the central character, Billy Moore, gets thrown into a brutal Thailand prison in this movie, the existence he leads looks excruciating. A stranger in a strange land, the muscular, always-worried-looking Billy (Joe Cole) is a boxer who endures staggering amounts of physical pain and then goes and blows his earnings on drugs. He’s self-medicating in a sense but he’s also just a guy who likes to get wasted and is belligerent about his perceived right to do so.

When the Thai police bust up his drug-filled apartment and drag him off to jail, Billy is befuddled but defiant. He’s so messed up that it takes him quite a while to process what’s happening to him. Early on, he’s thrown in a prison ward, almost literally stacked with other prisoners. He winds up sleeping next to a corpse that night. He seems less bothered by it than the viewer is.

One thing about Thai prisons: there’s not much concern about what clothes you’re wearing. Because it’s tropically hot, the inmates walk around in short shorts, underwear, sometimes nothing. The movie has an abundance of water imagery—in the monsoon season the prison yard takes a beating from the rain, and Billy is often depicted under a stream of clear water, which never washes away his sins. Which he keeps committing while imprisoned. He doesn’t speak Thai, he has no family nearby—the one person who visits him early on is a kid who he was training for a boxing undercard—and no means. But Billy still wants what he wants, and much of the time he wants drugs. Marijuana, smokable heroin, that kind of thing.

His inability to pay for the goods makes a lot of trouble for him, particularly with the prisoners who are tattooed from head to toe with a lot of threatening-looking artwork.

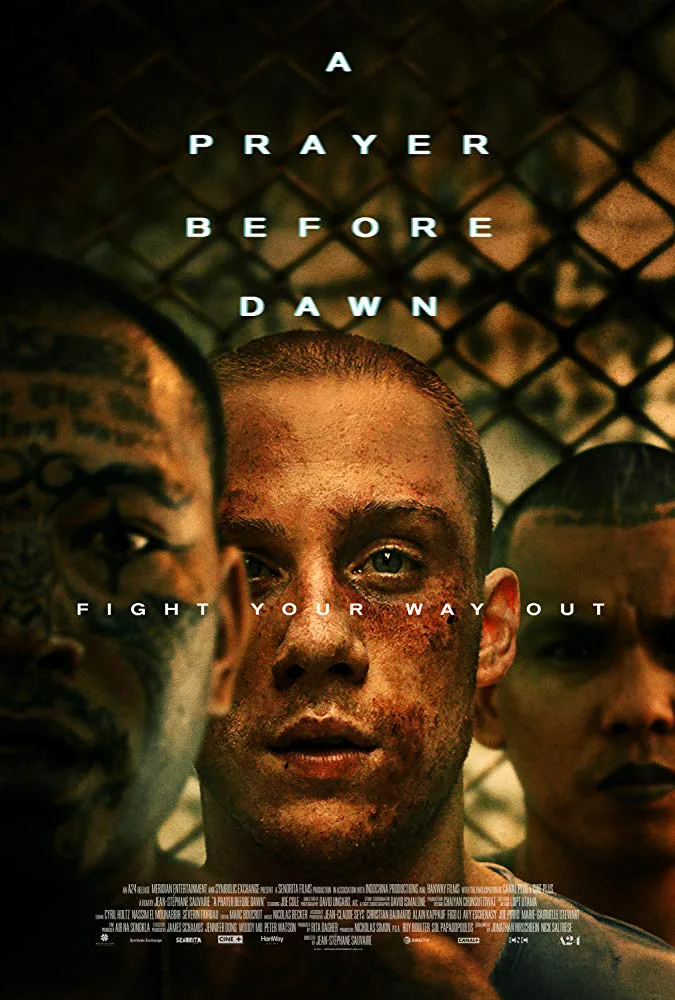

Directed by Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire, “A Prayer Before Dawn” often plays like an art-film variant of “Midnight Express.” It’s true that Alan Parker’s 1978 film had its high-flown touches, but what goes on here is rather different. The realistic, immersive shooting style is meant to throw the viewer right in the prison with Billy, and the movie dispenses for the most part with backstory or any other of the conventional features that allow viewers to sentimentalize the brutality of what these characters experience. And what they experience is almost nonstop brutality. At the same time, the director’s approach avoids the casual but pronounced racism of “Midnight Express” and steers clear of exploitative perspectives.

Eventually, Billy starts to realize that the only way he can survive in prison, and restore some meaning to his life, is by taking up boxing again. Qualifying for the prison’s team, he makes some friends, guys who are trying to reform. These fellows held some unusual ideas prior to trying a more straight-and-narrow life. “When I realized I was going to be in prison for five years, I went wild,” one of the boxers tells Billy. “I killed three people.” Which, of course, yielded him a life sentence. So, all right, then.

Billy is hardly a stranger to such willfully self-destructive behavior. He charms one of the transsexual women who work at the prison’s dispensary, and they begin an affair, but in a jealous rage he goes wild himself, and winds up in solitary before a tournament that could spell his ostensible comeback. Health issues also intervene. One of the movie’s most staggering moments occurs late in the movie, when Billy, in a hospital, finds himself able to walk out, and roam free for a while, which brings an existential question his way. How he answers it is both thought-provoking and unavoidable.

This movie is a remarkable feat that requires a strong stomach to sit through. I was unaware, prior to seeing it, that it’s based on a true story, and the movie’s coda was that much more powerful for me as a result. But even knowing that going in, “A Prayer Before Dawn” will put you through the wringer and eventually make you glad you went.