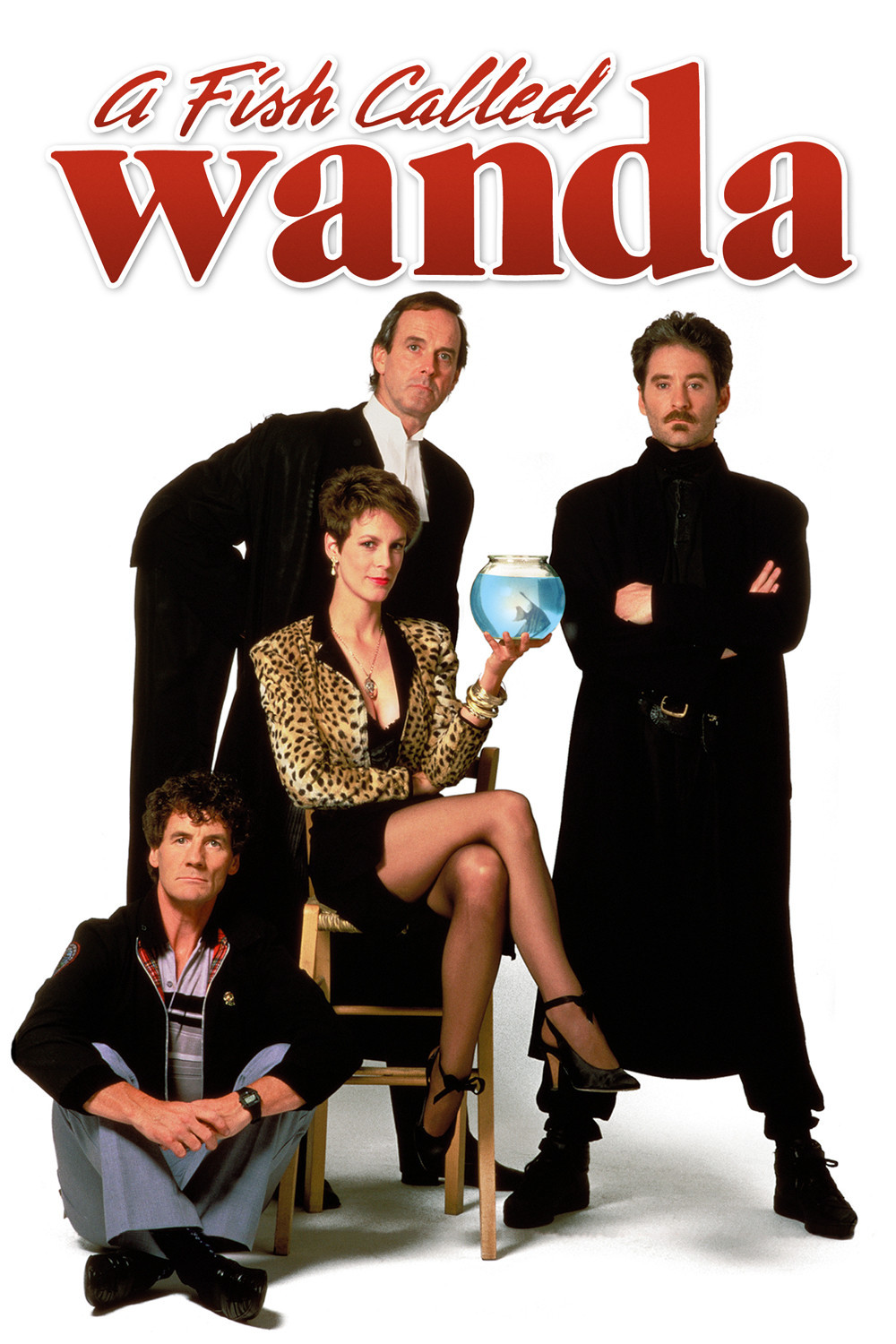

This may be a purely personal prejudice, but I do not often find big-scale physical humor very funny. When squad cars crash into each other and careen out of control, as they do in nine out of 10 modern Hollywood comedies, I stare at the screen in stupefied silence. What is the audience laughing at? The creative bankruptcy of filmmakers who have to turn to stunt experts when their own ideas run out? I do, on the other hand, laugh loudly at comedies where eccentric people behave in obsessive and eccentric ways and other, equally eccentric, people do everything they can to offend and upset the first batch. In “A Fish Called Wanda,” for example, a character played by Kevin Kline is very particular about one thing: “Don’t you ever call me stupid!” He is then inevitably called stupid on a number of occasions, leading to the payoff when his girlfriend explains to him in great detail why and how he is stupid and lists some of the stupid things he believes (“The London Underground is not a political movement”).

I also like it when people have great and overwhelming passions – passions that rule their lives and are so outsized they seem like comic exaggerations – and then their passions are deliberately tweaked. In “A Fish Called Wanda,” for example, Michael Palin is desperately in love with a tank of tropical fish, and so Kline, who is equally desperate about discovering the whereabouts of some stolen jewels, eats the fish, one at a time, in an attempt to force Palin to talk. (The fact that Kline also stuffs French fries up Palin’s nose gives the scene a nice sort of fish-and-chips symmetry.) Another thing I like is when people are appealed to on the basis of their most gross and shameful instincts, and surrender immediately. When Jamie Lee Curtis wants to seduce an uptight British barrister (John Cleese), for example, she simply wears a low-cut dress and blinks her big eyes at him and tells him he is irresistible. This illustrates a universal law of human nature, which is that every man, no matter how resistible, believes that when a woman in a low-cut dress tells him such things she must certainly be saying the truth.

“A Fish Called Wanda” is the funniest movie I have seen in a long time; it goes on the list with “The Producers,” “This is Spinal Tap” and the early Inspector Clouseau movies.

One of its strengths is its meanspiritedness. Hollywood may be able to make comedies about mean people (usually portrayed as the heroes), but only in England are the sins of vanity, greed and lust treated with the comic richness they deserve. “A Fish Called Wanda” is sort of a mid-Atlantic production, with flawless teamwork between its two American stars (Curtis and Kline) and its British Monty Python veterans (Cleese and Palin). But it is not a compromise; this is essentially a late-1950s-style British comedy in which the Americans turn up to do and say all of the things that would be appalling to the British characters.

The movie was directed by Charles Crichton, who co-wrote it with Cleese. Crichton is a veteran of the legendary Ealing Studio, where he directed perhaps its best comedy, “The Lavender Hill Mob.” He understands why it is usually funnier to not say something, and let the audience know what is not being said, than to simply blurt it out and hope for a quick laugh. He is a specialist at providing his characters with venal, selfish, shameful traits and then embarrassing them. And he is a master at the humiliating moment of public unmasking, as when Cleese the barrister, in court, accidentally calls Curtis “darling.” The movie involves an odd, ill-matched team of jewel thieves led by Tom Georgeson, a weaselly thief who is locked up in prison along with the secret of the jewels. On the outside, Palin, Kline and Curtis plot with and against each other, and a great deal depends on Curtis’ attempts to seduce several key defense secrets out of Cleese.

The film has one hilarious sequence after another. For classic farce, nothing tops the scene in Cleese’s study, where Cleese’s wife almost interrupts Curtis in mid-seduction. Curtis and Kline slip behind the draperies while the mortified Cleese tries to explain a bottle of Champagne and a silver locket. The timing in this scene is as good as anything since the Marx Brothers.

And then there is the matter of the three murdered dogs. One friend of mine already says she won’t see “A Fish Called Wanda” because she has heard that dogs die in it (she is never, of course, reluctant to attend movies where people die). I tried to explain to her that the death of a pet is, of course, a tragic thing. But when the object is to inspire a heart attack in a little old lady who is a key prosecution witness, and when her little darling is crushed by a falling safe, well, you’ve just got to make a few sacrifices in the name of comedy.