Spike Lee‘s “25th Hour” tells the story of a businessman’s last day of freedom before the start of his seven-year prison sentence. During this day he will need to say goodbye to his girlfriend, his father and his two best friends. And he will need to find someone to take care of his dog. The man’s business was selling drugs, but his story could be a microcosm for the Enron thieves. What it has in common is a lack of remorse; the man is sorry he is going to prison, but not particularly sorry for his business practices, which he would still be engaged in if he hadn’t been caught.

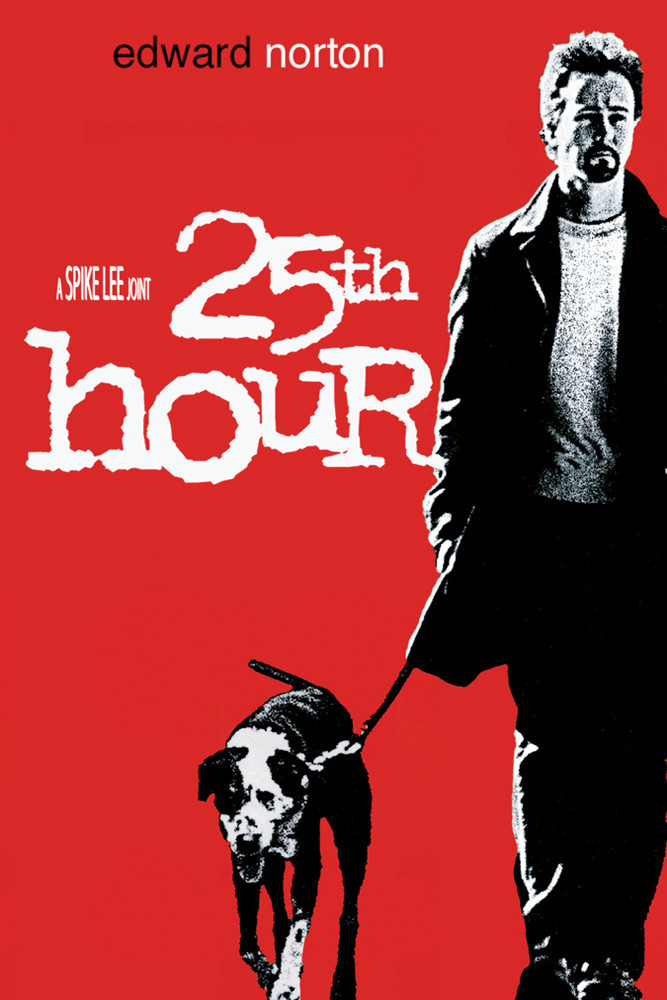

The man’s name is Monty Brogan. He is thoughtful, well-spoken, a nice guy. The first time we see him, he’s rescuing a dog that has been beaten half to death. He associates with bad guys–the Russian Mafia of New York–but it’s hard to picture him at work. He doesn’t seem like the type, especially not on the morning of his last day, when an old customer approaches him and he wearily advises him, “Take your jones somewhere else.” Monty is played by Edward Norton as a man who bitterly regrets his greed. He should have gotten out sooner–taken the money and run. He stayed in too long, someone ratted on him, and the feds knew exactly where to look for the cocaine. He dreads prison not so much because of seven lost years, but because he fears he will be raped. His friends see his future more clearly. They are Jacob Elinsky (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a high school English teacher, and Frank Slaughtery (Barry Pepper), a Wall Street trader. Talking sadly with Jacob, Frank spells out Monty’s options. He can kill himself. He can become a fugitive. Or he can do the time, but when he comes out his life will never be the same and he will not be able to put it together in any meaningful way. Frank’s verdict: “It’s over.” The film reflects this elegiac tone as it follows Monty’s last hours of freedom. He has been lucky in his girlfriend, Naturelle (Rosario Dawson), and in his father, James (Brian Cox). Although he suspects that Naturelle could have been his betrayer, we see her as a good-hearted young woman who knows how to read him, who observes at a certain point in the evening that Monty doesn’t want company. The father, a retired fireman, runs a bar on Staten Island. Most of his customers are firemen, too, and the shadow of 9/11 hangs over them.

Monty has given his father money to pay off the bar’s debts. He has moved with Naturelle into a nice apartment. Both the father and the girl know where the money comes from. His dad disapproves of drugs but has a curious way of forgiving his son: He blames himself. Because he was a drunk, because his wife died, it’s not all Monty’s fault.

The screenplay is by David Benioff, based on his novel. It contains a brilliant sequence where Monty looks in the mirror of a restroom and spits out a litany of hate for every group he can think of in New York–every economic, ethnic, sexual and age group gets the f-word, until finally he sees himself in the mirror and includes himself. This scene seems so typical of Spike Lee (it’s like an extension of a sequence in “Do the Right Thing“) that it’s a surprise to find it’s in the original novel–but then Benioff’s novel may have been inspired by Lee’s earlier film.

There are two other sequences where we see Lee’s unique energy at work. In one of them, also from the book, his father drives Monty to prison and, in a long voiceover monologue, describes an alternative to jail. He tells his son that he could take an exit on the turnpike, head west, start over. In an extraordinary visual illustration of the monologue, we see Monty getting a job in a small town, finding a wife, starting a family, and finally, old and gray, revealing the secret of his life. Wouldn’t it be nice to think so. Brian Cox’s reading of this passage is another reminder that he is not only the busiest but the best of character actors.

The other sequence involves Jacob, the Philip Seymour Hoffman character. He is a nebbishy English teacher, single, lacking social skills, embracing his thankless job as a form of penance for having been born rich. He is attracted to one of his students, Mary D’Annunzio (Anna Paquin), but does nothing about it, constantly reminding himself that to act would be a sin and a crime. On Monty’s last night he takes Naturelle, Jacob and Frank to a nightclub, and Mary is in the crowd of girls hoping to get past the doorman. From across the street she shouts at Jacob: “Elinsky! Get me in.” And we think, yes, she would call him by his unadorned last name–the same way she refers to him among her friends. She does get in, and this continues a parallel story. She is precocious with sexuality yet naive with youth, and the poor schmuck Jacob is finally driven to trying to kiss her, with results that will burn forever in both of their memories. How does this story fit with Monty’s? Maybe it shows that we want what we want, no matter the social price. And maybe that’s the connection, too, with Frank, who invites Monty over to his big apartment in a building literally overlooking the devastation of the World Trade Center. He has never thought of moving, because the price is right. All three men are willing to see others suffer, in one way or another, or even die, so that they can have what they want. The movie suggests a thought that may not occur to a lot of its viewers: To what degree do we all live that way? The film is unusual for not having a plot or a payoff. It is about the end of this stage of Monty’s life, and so there is no goal he is striving for–unless it is closure with Naturelle and his father. He may not see them again; certainly not like this. The movie criticizes the harsh Rockefeller drug laws, which make drugs more profitable and therefore increase crime. We reflect that when Monty sold drugs, at least his customers knew exactly what they were buying, and why. That makes him a little more honest than the corporate executives who relied on trust to con their innocent victims out of billions of dollars.