HOLLYWOOD — “Make a reservation at Le Bistro,” Groucho Marx said over the telephone. “And make sure you make the reservation. I went there once with some schnook from Life who thought you could walk right in. And for God’s sake make sure it’s even open on Sunday. If it isn’t, make a reservation at the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel. To me it’s just a device to get a free lunch. If I mention ‘Minnie’s Boys,’ it will be strictly by accident. And for God’s sake don’t bring along any gadgets, any of that electronic gear….”

Shall I pick you up?

“I’m not that kinda girl.”

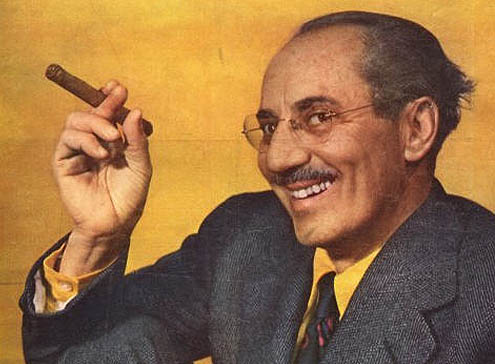

The voice was soft and serpentine, with a sort of off-balance New York rhythm to it that curiously reminded you of his walk; he kept sticking out a foot just in time. And Le Bistro indeed being closed on Sundays, that was more or less the way he crossed the Polo Lounge: taking aim at a chair and avoiding a collision at the last possible moment by a recovery that seemed something less than studied. At 74, Groucho looks essentially as he has always looked. Perhaps the mustache once wasn’t as gray.

“It doesn’t make a damn bit of difference, anyway, what I say about ‘Minnie’s Boys’,” he said. “It might be the most brilliant musical to hit Broadway in years. It might be a bomb. There’s a big advance sale, but that doesn’t mean a goddamn thing. The word gets around fast, with Newman on TV and three or four other knife wielders warming up.

“Critics. I know about critics. When we were working Chicago I used to go to the movies with Carl Sandburg. He was the movie critic of the Daily News at that time. He always instructed me to wake him up 10 minutes before the movie was over. I’d be asleep too, but I had myself trained.”

Why go to the movies if you’re just going to sleep?

“Because Sandburg got free passes and it was goddamn cold in Chicago in the winter, that’s why. Besides, it didn’t matter so much if you took a little nap. Movies in those days were easier to understand. Movies today, I can’t follow them. The Marx Brothers pictures were pretty simple, they had rudimentary plots. But that ‘Midnight Cowboy‘…I went to see it and you know what it’s about? It’s about a stud and a pimp, that’s what it’s about. I’ll take the Marx Brothers pictures any day of the week. I hated that movie. Those were detestable characters.

“Still, I don’t approve of keeping children out of those pictures. Maybe they understand them better than I do. By 16 or 17, they know all the basic variations anyway.” A pause. “I barely understand variations by Haydn and Brahms….”

The waiter came and Groucho said that when he was in need of a waiter, he would make his desire known.

“I liked that wife-swapping comedy though,” he said. “What was its name? Ethel and Mary and John and Joe, that one. It went to just about the right length of dirtiness. I saw a TV show the other night you wouldn’t believe. There was a sketch about a couple that had just gotten married, see? In the hotel curiosity shop, there’s a chastity belt for sale. The wife tries it on and she can’t get it off. They call in the plumber, they call in the locksmith…I thought I’d never see the day.”

He shook his head in disbelief. “Comedy is changing,” he said. “When we were coming up through vaudeville, we had the time to work at a sketch until we had it right. When we played Chicago, we played a year and never left the city. There was a theater every four blocks. And then when you left Chicago there was Decatur, Aurora, Elgin, Champaign…you could work out new stuff. The audience was your best writer.

“These days…” He said it in a tone of voice that required a sip of water afterward for timing. “Do you realize there are twelve books out on the Marx Brothers not counting the ones we wrote? We’re getting to be like Abraham Lincoln. But a lot of these books, I’ve looked at them, they’re crap. They do a new kind of writing. They rent our movies, tape-record them, and write down all the good jokes in their books. Quite a writing feat!

“In ‘Minnie’s Boys,’ they’ve taken a different tack. The play won’t have any Marx Brothers material. We’re fooling them. It’s about when we were youngsters. I’m the production consultant. That means they give me some money. I’m the guy who’s supposed to holler if anything stinks. I’m keeping quiet. If anyone says I had anything to do with it, I can deny it. I might even say I never heard of it. It’s got a big budget. Comes to about $100,000 a brother.”

What’s your opinion of the casting?

“I haven’t fished in years.”

He studied the menu. “Bay Shrimp Salad, tossed at your table,” he mused. “I wonder if they bring in Sandy Koufax?” He ordered a small orange juice and eggs Benedict, No coffee. Tea.

“Of course,” he said, “the play is absolutely based on the facts. Ha. It’s so good not to be in the damned thing. I’ll sit there on opening night and keep an eye on the guy playing Groucho. If I don’t like him, I’ll run down the aisle shouting: ‘I was better than that!’ Well, maybe I wasn’t….”

What did you think about your last movie, “Skidoo?”

“I don’t think it ever played in a theater, did it? I saw it one night with Preminger at a preview in San Francisco. I don’t think anybody understood it. I didn’t. He’s a nice guy, but he’s not a comedy director. I only did five days’ work on the picture, you can’t blame me. It had Gleason too, you know. I was lousy, When I say I was lousy…I wasn’t any worse than the rest of the cast. But, they gave me a lot of money and I only worked five days. I played God. Jesus, I hope God doesn’t look like that.”

The orange juice came and the eggs and the waiter was sent for the tea.

“I think Preminger wanted to make a movie about the hippie movement,” he said. “That’s what I think. You know, they wanted me to testify in Chicago at the conspiracy trial. They wanted to bring me in as an expert on humor. I turned them down flat. I’m not too familiar with the case; I was afraid I might be held in contempt of court. I kept my nose out of it. I told them, why don’t you get Steve Allen or Paul Newman, one of those guys always trumpeting about freedom of speech?

“I was afraid the judge might resent an ancient comedian in there. Even Nicholas Ray called me. I guess they thought I might have some fun with the judge or something. A week in the cooler, that’s what I’d get. I said they could get funnier fellows than me. Johnny Carson. I spoke to one of those fellows. Hoffman or Rubin, I don’t remember. I asked him how he made a living. He said he got $2,000 for a book about the case. How long ago was that? I asked him. Oh, about a year ago, he said.”

With the tip of a knife and the edge of a fork, Groucho performed an intimate and delicate operation on one of the eggs.

“I told them to get somebody else,” he said finally, and then he added very softly: “Their request that I testify…it wasn’t a compliment, I don’t think.”

A silence was permitted to unfold out of respect for the eggs.

“‘Minnie’s Boys’ opens at the Imperial on March 24,” Groucho said at last. “You’d better put that in. My son Arthur is one of the authors. That’s another reason I don’t want to get in too deep. They’re doing a good job, I think…”

Does “Minnie’s Boys” more or less follow real life?

“More,” he said. “It’s an interesting story. At least, it’s interesting to me. My father was a tailor and a very bad one. His contribution to the sartorial world was about as large as his contribution to the Marx Brothers. We got into show business because our mother’s brother was Al Shean, of Gallagher and Shean, and he was pulling down $150 a week. Mother knew a good thing when she saw one.

“Minnie had a native shrewdness. And she was pretty. That was a big help in getting us started. Harpo worked in a butcher shop at the time, delivering meat. Chico was playing the piano in a place that was not too savory, except for him. That is, he was the only thing savory about it. I could sing well, and Chico could sing, and Harpo couldn’t sing at all so we made him the bass and he growled. We formed a group named the Three Nightingales.”

The hint of a smile crossed his lips. “The Three Nightingales,” he repeated. “This was during the stage when our voices were starting to change, so we tried a couple of jokes on the audience to see, if they’d work. Before we knew it, we were a comedy act. Mother was shrewd in getting bookings, small bookings. Father quit tailoring and became the cook. He couldn’t make a suit anyway. He eventually became a very good cook. My mother would invite bookers to dinner. Father became a hell of a cook. And he was a very bad tailor. We got a lot of bookings through father’s cooking. He was a lousy tailor, though.”

How do you feel about Shelley Winters playing Minnie?

A wicked grin. “I’ve never felt about Shelley Winters. I’d like to some time. Never got the opportunity…You know, a lot of these big Broadway musicals these days, the stars sign short-term contracts. I don’t know if Shelley Winters has or not. But I suggested to Arthur that if she drops out after six months, they ought to get Pearl Bailey.

“Of course, I’m happy they’re doing the musical. It’s an honor; I look at it that way. For that matter, I was voted man of the year at Yale this year. You know what that means. It means you go to Yale and make a very funny speech for which you don’t get paid. I don’t need the experience. I have spoken. I spoke at the Columbia School of Journalism 18 years go.”

The eggs had been disposed of, and now Groucho lit a long and expensive cigar, his first of the afternoon. It was a time for reflection.

“I get a lot of mail,” he said. “A hell of a lot. The reason I get so much, I think, is that a lot of it might have been sent to Harpo and Chico if they were still alive. I attribute it to that…”

He inhaled in meditation. “But they’re gone. Gone to the hereafter. You know, I don’t believe in religion, or the hereafter. Not at all. I discussed the subject with Chico and Harpo a couple of years before they died. They said they’d get in touch with me if there were a hereafter. But you know what?” He examined the ash of his cigar thoughtfully. “I never heard a word. Not a goddamn word.”