Rupert Everett’s first theatrical performance was in a play by Oscar Wilde and he has appeared on screen in Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband” and “The Importance of Being Earnest.” In “The Happy Prince,” named for Wilde’s fairy tale about a jeweled, gold-covered statue who sacrifices himself for others, Everett plays Wilde in his last years, remembering his past. In an interview with rogerebert.com he talked about what mattered most to Wilde and why he is his favorite director.

You’ve played Wilde characters on stage and in films. How did that help you create the character of the man who wrote the plays?

In terms of trying to get the phraseology under my skin. In writing the film, being in the plays was very, very helpful. In terms of playing him on film, it was an invaluable experience because it gave me an idea of how it could work.

Is there a favorite Wilde character you have especially enjoyed playing?

The first play I was in, which really started me thinking in terms of performing, was The Picture of Dorian Gray and I played Lord Henry Wotton. That was my favorite Wilde part.

In the film, you have a Wilde quote from The Ballad of Reading Gaol: “Yet each man kills the thing he loves.” Do you think he believed that? Was it true in his life, or was it the other way around, and was it Bosie, the young man Wilde loved, who in essence killed him?

It’s difficult to know what it means, really. I put it over Bosie in my film because it is about Bosie’s destruction of Oscar. I think he is destroyed by Bosie but he destroys other people, too. He’s quite a destructive character in some ways.

And it is so poignant in the film that the one person who truly loves him, Robbie, is the one whose love he cannot accept.

Exactly. The real love affair was between him and Robbie. And the other one was like a comet, a very dangerous one. That’s what killed him, I suppose, in a way.

And I’ve always wondered about the Wilde story that gives your film its name, The Happy Prince. It seems out of place with his more distant, observant work, whether comedy or drama.

It was written much earlier. But that’s a good point with a lot of Wilde, in a way, whether it is sincere or synthetic. Sometimes it is too syrupy. But I think the fairy stories are wonderful, myself and particularly if you think, like I do, of Wilde as the happy prince himself, a beautiful gilded statue that at the end has nothing left.

Tell me, as a writer, how you decided on the film’s intricate structure, with images and characters from the past juxtaposed, often with surprising, telling, symmetry, with Wilde’s last years.

I loved the idea of the death bedroom, like the wonderful portrait of Chatterton, and other portraits of people on their deathbeds. Wilde’s deathbed was definitely where I wanted to set my story. Also bearing in mind the other three films that had been made about him don’t really approach that whole area, so it was kind of virgin territory. I wanted to make it about the deathbed, and about dying, and about the brain kind of collapsing and memories like trapped gas coming out and the room expanding suddenly into a beach and then contracting back into the room, and expanding again, and the window, and suddenly you’re somewhere else. That was my original plan and it grew from there. That was my modus operandi, so to speak.

Did you do a lot of research?

I think I’ve read everything there is about Wilde, and read every letter, and all the contemporary accounts, which are great, and all the modern ones, which are amazing. And as I said, I was in a lot of the plays, so I got the dialogue under my skin. And so I knew very much the Wilde I wanted to present, or paint, and it was the one who was a kind of vagabond, rather than the Cafe Royal version, a man smelling of sweat and armpits and cigarettes and darned socks and rotting teeth, and this memory of greatness. So when he goes to a bar and picks up a boy and says to him, “I used to be very famous,” the boy just thinks he’s deranged. That’s how I imagine Wilde was in his exile.

We tend to think of him as a dandy with rapier-like wit, trading barbed bon mots with Whistler and caricatured by Gilbert and Sullivan in “Patience.”

At the end of his life, he was more whole than in the earlier days. With Whistler, he was the underdog, always. Whistler was the one everyone took seriously, not Wilde. The genius of him with Gilbert and Sullivan was taking the bad publicity and running with it, which is why he is such a modern celebrity, almost like Kim Kardashian and the sex tape. Making that work for him is genius, really.

When was he happiest?

In my film, I have him happiest when he’s in a knocking shop and he’s just had sex, and there are cockroaches climbing up the bed. He says, “I don’t think I’ve ever been happier in my life.” I think he was one of those people who was capable of happiness all the time. Of course his exile is a tragedy and my film is a tragedy, but he approached it with quite a humorous mindset, a curious mindset. He wasn’t detached and sitting in a gloom all the time. He carved his own constitution on the street corner and replaced all the celebrities and royalty with rent boys and criminals and had—largely—quite a nice time.

It makes him a terribly appealing character to me, despite all his faults.

You sing a very apt song in the film, “The Boy I Love is Up in the Gallery.” Where did that come from?

It’s from the Laurence Olivier film, “The Entertainer.” It’s sung by his character’s wife. That was the most challenging scene to film. It was a huge scene, a singer, a whole orchestra, dancers, a fight, and we had only one day to do it in.

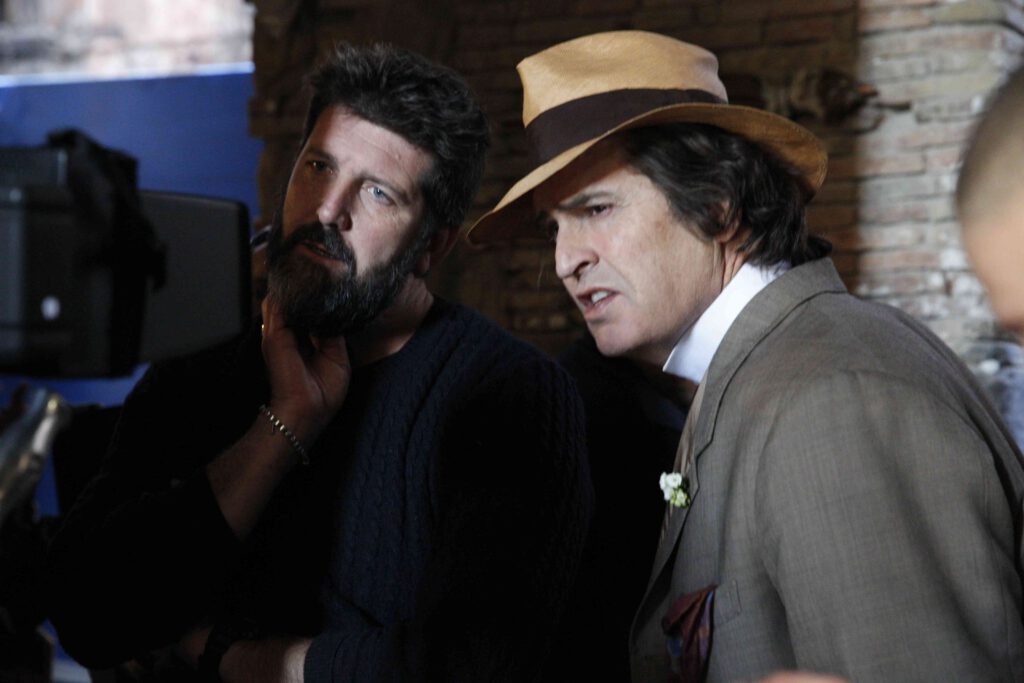

Was it a challenge to act and direct?

I’m my favorite director. I helped myself enormously in the edit. The best directors let the actors alone as much as possible, let them breathe. Actors like being given their space.

How did you create all those period settings and costumes?

Mostly you’re just seeing collars, cuffs, dresses, hats, and hair, so costumes are very important. I spent all the money in the budget on them. It’s a road movie in a way so it’s a big design challenge to make all that look right and be right. That’s something I feel very proud of. We made most of the film in Bavaria, where Oscar Wilde never went and the architecture doesn’t really look anything remotely French. So I found these three old castles in Franconia, and they were amazing, and inside them I kind of made a movie studio in a way, and all the rooms in the film take place in the castle.

We did our exteriors in Naples. We never went to Paris. Not difficult, but a challenge, and exciting.

Is there anyone at all like Wilde today?

No, I don’t think so. First of all, he was a classical genius. He was a great classicist, and that kind of brain doesn’t really exist anymore, people who train themselves in that area. If you are trained in that area, you are a very particular kind of person. There are flamboyant people, but they are not flamboyant with his intelligence. I don’t think there is anyone like him any more.