In a blistering segment on his Emmy-winning HBO program, “Last Week Tonight,” John Oliver dissected unsettling comments made by Newt Gingrich at this year’s Republican National Convention. “I think we can all agree that candidates can create feelings in people,” said Oliver. “What Gingrich is saying is that feelings are as valid as facts. So then, by the transitive property, candidates can create facts, which is terrifying, because that means someone like Donald Trump can essentially create his own reality.” The same could be said of David Irving, a Holocaust denier who sued revered historian and professor Deborah Lipstadt for libel, forcing her to prove in court that the Holocaust actually took place. What’s astonishing is that this trial occurred a mere two decades ago. Now director Mick Jackson and screenwriter David Hare have brought the story to life on the big screen, with Rachel Weisz inhabiting the role of Lipstadt. Tom Wilkinson and Andrew Scot play key members of Lipstadt’s defense team (lawyer Richard Rampton and academic Anthony Julius, respectively), while Timothy Spall is indelibly blood-curdling as Irving.

Lipstadt spoke with RogerEbert.com about our conspiracy theory-driven culture, Weisz’s spot-on accent and why the film deserves to be viewed as much more than a Trump allegory.

I saw “Denial” at its premiere in Toronto, and mentioned Mick Jackson’s brilliant HBO film, “Temple Grandin,” during the Q&A.

Oh that was a wonderful film. When Mick’s name was first mentioned to me, they told me that he had directed films like “The Bodyguard” and “L.A. Story,” and it was only afterwards, when I was reading his bio, that I realized he had also made “Temple Grandin.” I once attended a conference at Trinity College with a friend of mine, and he told me about his son, who is autistic. The Israeli army had made accommodations for his son, and he was very touched by that. I told him about the film “Temple Grandin” and he said, “Not only do we know the movie, we have her book.” She had given his son hope.

What was it like collaborating with David Hare, as well as with Mick Jackson and Rachel Weisz, on this project?

There were all sorts of false starts, as there are on any movie, and they eventually decided to bring in Participant Media and BBC Films. They called me and asked, “Do you know the name David Hare?” and I said, “Of course, I know the name. I’m not living under a rock.” [laughs] They told me that he was thinking of coming onto the project, and they wanted me to go to London to meet him. Within three days, I was on a plane to London. We had tea together and met with Richard Rampton and Anthony Julius. David and I got together a few more times after that, and during our fourth meeting, he decided that he would take on the script. He came to Atlanta to watch me teach, meet my friends, and see where I lived. Then I received versions of the script and was asked to comment on them. I didn’t comment on every line or his artistic approach, but I did say if something wasn’t accurate, and he was very open to my feedback. When Mick came on, I met with him a number of times. He would ask lots of detailed questions because he comes from the world of documentary, having directed such programs as BBC’s “The Ascent of Man” with Jacob Bronowski.

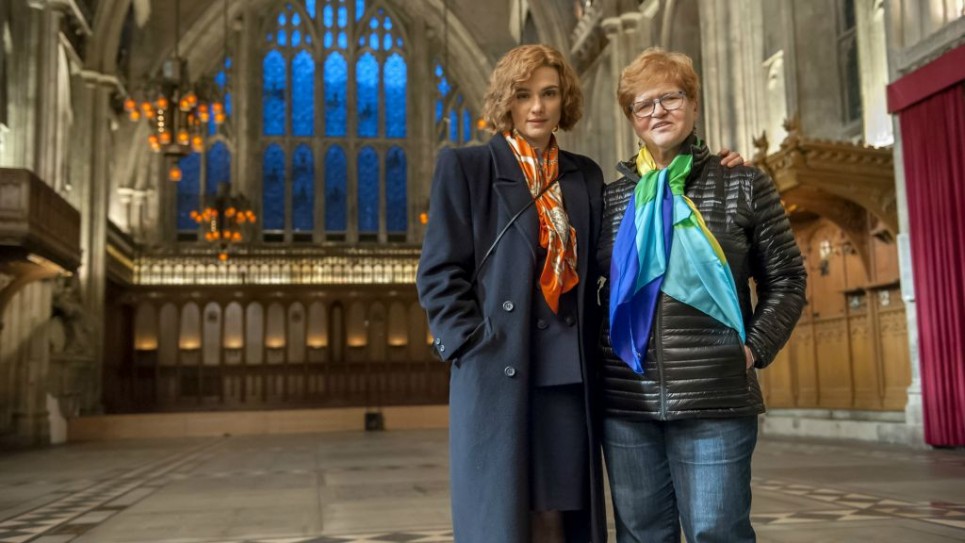

When Rachel came on, she called me right away and we spent 40 minutes on the phone together. I spent two days with her at her home in New York, and she pumped me for as much information as she could. It was very helpful to her during her process of understanding me and creating the character. At the end of our time together, she said, “I’m not going to recreate you as Helen Mirren recreates the Queen. I’m going to take all the stories you told me, along with the script and the direction I’m given on the set, and I’m going to put it all together as a composite, which will be my understanding of who you are.” Some of my very close friends have seen the film and they’ve said, “Love the film but she didn’t get this or that exactly right,” and I explain to them that she wasn’t mimicking me. This was her interpretation and I think she did a great job. I laugh when people complain about her accent. I have a little four-year-old friend with whom I read every night, and her parents were watching the trailer for the film during a recent visit. She looked up and said, “Why does that lady sound like you?” If a four-year-old thinks Rachel sounds like me, that is what I sound like.

Immediately after the film ended, I turned to the couple sitting next to me and said, “Timothy Spall made a great Donald Trump,” and they completely agreed. Beyond those similarities, “Denial” does capture the bullying nature of modern American culture.

I don’t want “Denial” to be an anti-Trump film for an important reason: the message of the film is much bigger than one person. You are absolutely right that we live in a bullying culture. David Irving is a bully—he’s bullied people by threatening lawsuits, getting people to settle, etc. But more importantly, we live in a conspiracy theory-driven culture where people say that 9/11 was an inside job, or that Sandy Hook was set up by the anti-gun people in order to get anti-gun legislation legislation passed. Facts don’t seem to matter to these people. If they believe it and if they are going to insist on it, that’s enough. This served as the inspiration for Stephen Colbert’s concept of “truthiness,” as well as The Economist’s definition of “post-truth” politics. This film is about Holocaust denial, and about the truth of the Holocaust. It’s about how there are not two sides to every story, and that there is a difference between fact, opinion and lies. If I say to you it is my opinion that 9/11 never happened, or that slavery never happened or that Elvis is alive—that’s not an opinion, that’s a lie, even if I insist upon it. What we see today are people taking lies, insisting on them as their opinion and hoping to shape the facts. Holocaust deniers are a perfect role model for these people.

Irving’s penchant for baiting the media with soundbites like, “No holes, no Holocaust,” is evocative of how opinions are often taken on issues before they are properly explored. You can “like” a headline online without reading the article.

It’s all a part of the 24-hour news cycle. I don’t want to beat up on the Internet because I couldn’t do my work without it. I always describe the Internet as a knife. A knife in the hands of a murderer is a weapon, a knife in the hands of a surgeon is an instrument to save a life. But what has happened with the Internet is that people with crazy ideas have found each other, and they can hide behind false identities and become trolls. They can insist that there were Muslims dancing on New Jersey rooftops after 9/11, even though there is no evidence to prove it. It’s very, very dangerous, and our movie speaks to that. It wasn’t our goal to make an anti-Trump movie. When we started making the film in December, no one thought Trump had a chance. He was a joke at that point. If you merely focus on him rather than the bigger issues of the film, you fail to see the forest for the trees.

I never took the macro view when the film was being made. Each day, I was asked questions like, “Would you have worn hiking boots or sneakers when you went to Auschwitz?” I dealt with each piece at a time, and I took a similar approach to the trial. I never sat down and said, “I’m going to bring down the world’s leading Holocaust denier,” or, “I am fighting this on behalf of the Jewish people or the survivors or the people who believe in truth.” I slogged my way through each day. There’s a scene in the movie which I didn’t pick up on until my third viewing where my character comes back to Emory and asks her class, “Who here thinks they would’ve hidden Jews? You all think you would’ve been brave, but you can’t know what you’re going to do until you are faced with [the dilemma].” It’s only in hindsight that certain actions are called “heroic.” It always makes me uncomfortable when people call me heroic, because I never thought of myself as that. I just knew that if I didn’t fight this guy, he wins, and if he wins, history gets mangled, people who suffered get hurt and truth gets thrown out the window. I couldn’t be the vehicle to let that happen.

One of your greatest achievements is how you’ve made facts tangible and undeniable through your work for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Thank you very much for saying that. My initial job for the museum was to do some of the research on America during the Holocaust, and provide them with raw material while outlining the issues. In the permanent exhibit, there’s a whole section of videos on the American response, and that is based on my research. After I did that, President Clinton appointed me to be on the Holocaust Council, and when I stepped down, I got a fellowship to do research there. After that, President Obama reappointed me. So I think I am the only person who was a worker, a member of the Council and got a fellowship. The Holocaust Museum was very helpful to us in arranging the filming at Auschwitz, which has very strict rules against filming on the grounds. It was a team effort. They allowed us to bring the camera inside the grounds, but the actors remained outside. The rest of the footage was shot on a set in England. After we had a finished cut, one of the producers flew to Krakow, took a car to Auschwitz, screened it for them, received a very positive response, and then flew back to London. If we were going to make a film about the truth of Auschwitz, we had to know that we got it right and they were the ones to tell us we got it right.

Was it important to you that the court transcripts were preserved verbatim in the screenplay?

Oh absolutely. Before he wrote a word of the script, David Hare said, “Deborah, anything that goes on in the courtroom will come from the transcripts, word for word.” That’s when I knew we had the right person. Everything that comes out of David Irving’s mouth is what he said in the courtroom. This was a movie about truth, and you couldn’t mangle the truth. It frustrates me that some of the reviews, even some of the positive ones, have said, “I wish there would’ve been a moment where Deborah stood up in court a la Jimmy Stewart in ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,’ or Norma Rae or Erin Brockovich.” It didn’t happen, and we weren’t going to put it in there. The closest it happened was at the press conference, but there was no confrontation. Including a scene like that would’ve felt false to us and to the whole enterprise. We weren’t going to pander to the audience, and the audience reactions have been unbelievable. The film was recently playing on a number of screens at the Angelika. I snuck into a theater during the film’s final scenes, and the audience applauded at the end.

Tell me a bit about your upcoming book, The Anti-Semitic Delusion: Letters to a Student, due for release next year.

I’ve taken all the things that my students have asked me over the years about anti-Semitism, and it very much fits with the topics of this movie—conspiracy theories and distortions and how necessary it is to understand the facts and not be beguiled by prejudicial stereotypes. It’s in the works, though I don’t think it will be a movie. [laughs] I know colleges are providing educational screenings of “Denial,” and I hope lots of young people see it, because the message is, you’ve got to be willing to be the uncomfortable guest at the dinner party.